The passing of my PhD advisor, my hero and greatest professional mentor

Although several of us will be publishing tributes to Michael Soulé in journals over the next few weeks, here I want to say a little more, in perhaps a more personal way. Some of this is drawn from a remembrance of Michael that I sent to about 40 of my past and present students, the direct heirs of Michael’s legacy.

Michael was, of course, both the Founder and first President of the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB), and visionary for the journal that premiered in 1987. This, of course after establishing himself as an outstanding evolutionary biologist.

My relationship with Michael began in 1987 when I was a conservation intern in Washington, DC (at the National Wildlife Federation). I was exploring whether it was possible to build a career where I generated science that could be applied to conservation. I had just finished an M.S. where I had been told more than once that there could be no such thing as a scientist committed to conservation. That seemed wrong to me, and my DC internship seemed to be proof that merging science and conservation was possible, but my certainty in that path was unsteady. And then I read Michael’s ‘yellow cover’ Conservation Biology book that had just been published (we called it the yellow book to distinguish it from his other books that collectively were the first to have the words conservation and biology in a title). At that transformative moment, both the reality and moral mandate of my future in conservation biology was eloquently sealed.

So I began as Michael’s PhD student at University of Michigan in 1988 the year after he founded SCB. We were both single and newly arrived at Michigan, and spent many hours conversing in Ann Arbor pubs. I had never met anyone with such outrageously broad vision, pure intellectual honesty, and unyielding commitment to conservation. Many of his (at that time) seemingly preposterous ideas crossed seemingly impossible boundaries: “integrated conservation from Yellowstone to Yukon!”; “research on gene flow and focal species to underlie a comprehensive ‘Wildlands Project”; “start a discussion about rewilding extinct species”; “span the gulf between population genetics and population dynamics modeling”; “extinctions are not driven by just factor or another but by a vortex of interacting causes”. And, of course, over it all, the then entirely radical idea of conservation biology itself, a discipline that Michael asserted must bring together totally separate (at that time) disciplines: evolution, physiology, ecology, biogeography, veterinary medicine, social sciences, wildlife biology, ecophilosophy (see Soulé 1985; What is Conservation Biology? Bioscience 35:727-734). Following the style of his mentor (he was Paul Ehrlich’s first PhD student!), Michael invited criticism of his ideas, and I provided it, both as a student and afterwards. But consider all those ideas now, and how Michael’s ‘preposterous’ vision have shaped me, you, and conservation science and the world.

Recently, after Michael suffered a blood clot and his end was rapidly approaching, a group of us had time to share emotions, and prepare. One of my former Soulé labmates, Sanjayan (now CEO of Conservation International) reminded me of another of Michael’s dimensions, one less known yet especially relevant these days: in 1987, Michael published in volume 1, issue 2 of the journal Conservation Biology a short letter called “Diversity”. This was 3 years before Nelson Mandela was released from jail, and during apartheid in South Africa. Read this piece, and you will see the depths and clarity of Michael’s intellect, the perfection of his prose, the breadth of his ethics

I leave you with two of Michael’s quotes that I have passed on to students over the past 25 years, sharing Michael’s heartbeat with the next generation.

The first, from Michael’s 1986 ‘yellow book’ that I mentioned earlier, is now embedded in the Epilogue of my Conservation of Wildlife Populations textbook. In my epilogue, I encourage students to: “… Trust yourself and question absurdity. Sometimes things will seem huge and scary, like you will never be able to take into account all those complex factors and interactions and contradictions. But if you’re honest and open about what you know, you’ll find that you actually know a lot. Michael Soulé dedicated one of the first books on conservation biology (Soulé 1986:12) to ‘the students who will come after, who will witness the worst and accomplish the most.’ That’s you.”

The second quote is from the closing chapter of Michael’s 1987 Viable Populations book:

“There are no hopeless cases, only people without hope, and expensive cases”.

In the grief of Michael’s passing, I take solace from all of the moments I had with Michael and all that I learned from him. And, I am filled with gratitude for all the moments I have had with my students, and all they have done. And for the ripples that Michael’s work has emanated across the planet, with so many people working so passionately on behalf of 10 million (or so) species that occupy our world.

-L. Scott Mills

Scott has contributed to several other tributes to Michael, including one in Conservation Biology and one in Nature Ecology and Evolution. Scott also recorded a birthday tribute to Michael for his recent 80th birthday.

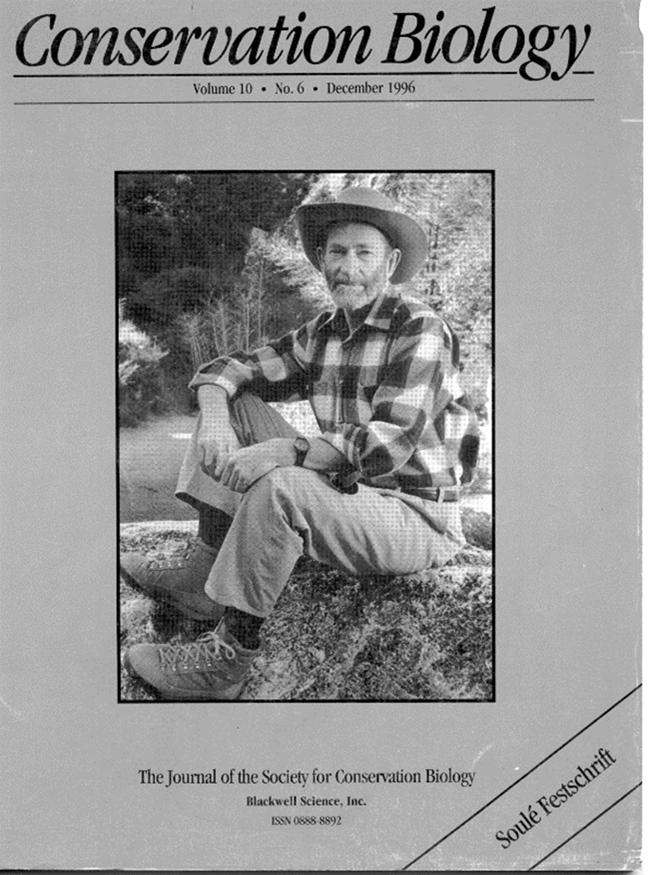

Feature Image: Michael on the cover of the journal that he founded, on the occasion of his retirement from academia in 1996.