Climate Impacts on Water Resources, Agricultural Production, and Farm Revenues upstream of Missoula County (Ravalli)

End-of-century hydro-economic model assessment

Cropland acreage in Missoula County has been steadily declining in the last few decades, reducing the importance of agriculture on the county’s GDP. This steady shift in the county’s economy from ranching and agriculture to other less water-demanding sectors, such as services and administration, has reduced the pressure that agriculture exerts on the county’s water resources. However, Missoula is located downstream of regions where agriculture is still a major economic driver. For instance, Ravalli County has a productive irrigated agricultural sector that relies on water from the Bitterroot River, which flows into Missoula’s Clark Fork River. Although Missoula’s agriculture may be easing the pressure on the county’s water resources, the potential upstream intensification of agricultural water use in Ravalli county may end up impacting streamflows in Missoula.

Using hydro-economic modeling methods we investigated the extent to which decisions made by Ravalli County producers to adapt to projected climate conditions will impact incoming flows and water availability in Missoula County. In this post we present model simulation results of projected end-of-century (2080-2100) changes in Bitterroot River streamflows, agricultural water demand in Ravalli County, and how land and water resources allocated to a few major crops grown in Ravalli may change under a range of business-as-usual climate change scenarios.

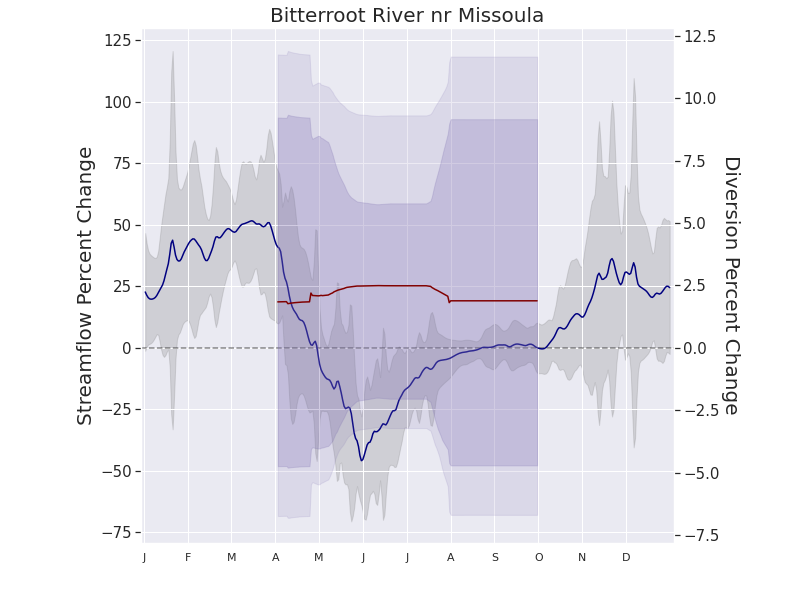

Figure 1: Using a suite of five Global Circulation Models (GCMs) and 11 years of satellite-data driven agricultural observations we consolidated the results of the hydro-economic model that encompass a range of climatic and agricultural end-of-century scenarios (2080-2100). Primary y-axis: Mean percent change in streamflow between baseline and end-of-century climate projections (blue line), with grey shading indicating 95% uncertainty envelope associated with interannual climate variability and climate model error. Secondary y-axis: Mean percent change in water diversions for irrigated agriculture between baseline and end-of-century projections (red line), with magenta shading indicating the 0.45-0.55 and 0.4-0.6 interquartile range of modeled diversions.

Using a suite of best-performing climate models for the Pacific Northwest, our hydrologic simulations anticipate that end-of-century streamflows in the Bitterroot River will change significantly. From late fall through early spring streamflows will be higher than current levels, while late spring through summer streamflows will drop (Figure 1). This change is to a large extent due to an earlier onset of spring and hotter summers, but also by alterations in the precipitation patterns during the year. This temporal change is aligned with projections detailed in the Montana Climate Assessment (Whitlock et al., 2017). Figure 1 also shows the projected change in water diversions from the Bitterroot River to support irrigated agriculture in Ravalli County. The change in diversions may increase by roughly 2.4% throughout the growing season (Apr. 1 – Sept. 30), although the uncertainty around this value is largely due to disagreements between the Global Circulation Models (GCMs) we used.

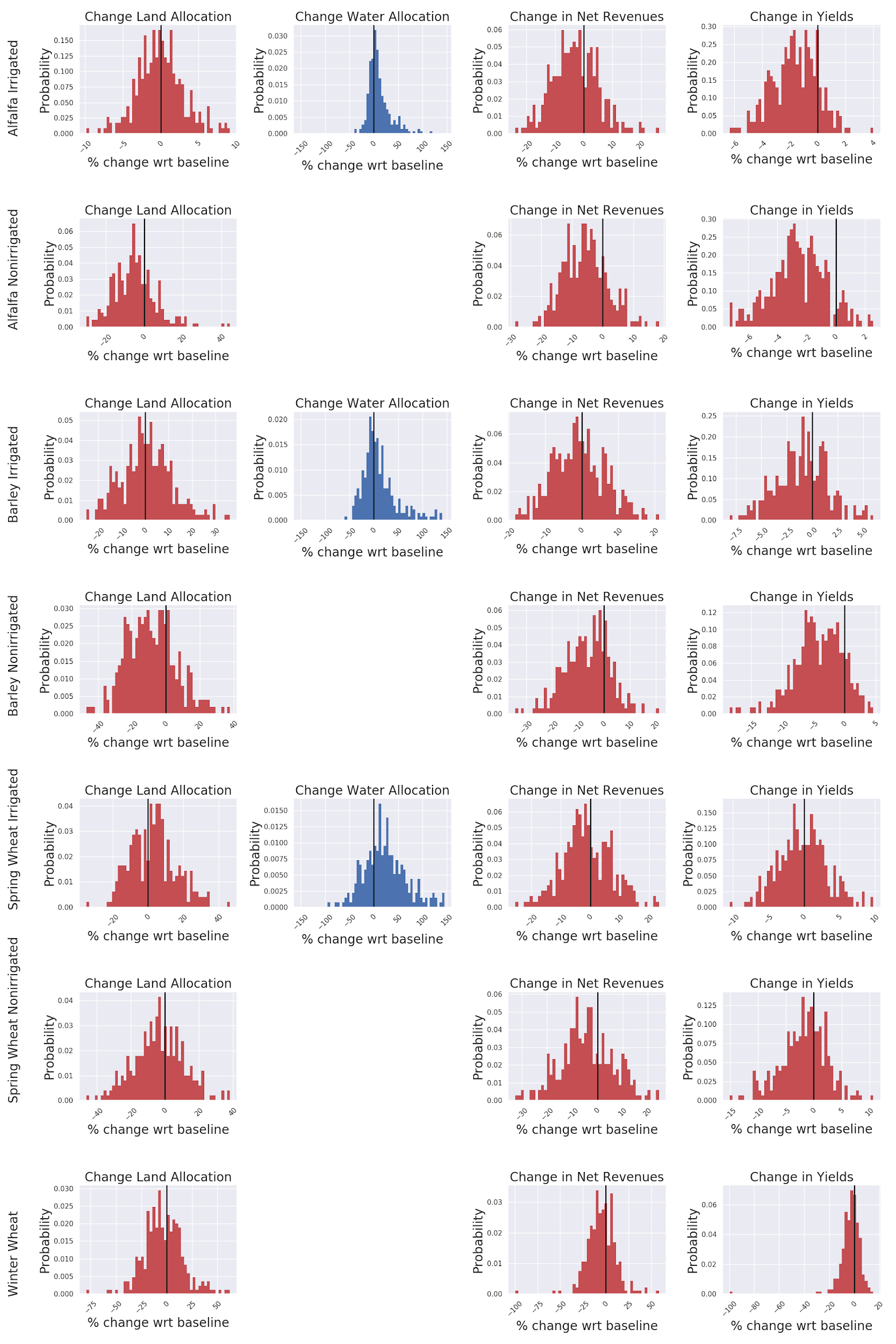

Producer’s will of course adapt to these new climatic conditions by reallocating land and water to the crops they believe will give them the highest return to investment. Although the suite of climate models predict a wide range of future conditions for western Montana, in general, they all project warmer air temperatures. However, the models disagree on how much additional warming, and on whether growing season precipitation will increase or decrease in the future. Taking climate projection uncertainties into account, it is expected that farmers will most likely reduce land allocated to rainfed crops (Figure 2). On the other hand, land allocated to irrigated spring wheat will increase, which also increases the need for additional water allocation to this crop. Although an interesting result for irrigated spring wheat is that even with more land and water allocations producers could still see decreases in production and net revenues from this crop.

Figure 2: Probability distribution of percent change in land and water allocation, crop production, and net revenues (columns) for some key crops grown in the state of Montana(rows). Percent change values in the histograms are between baseline (current conditions) and end-of-century climate projections (2080-2100) for Ravalli county, MT. (negative values indicate reductions wrt baseline, 0% means no change wrt to baseline)

Climate projection uncertainties along with large interannual variability in projected growing season temperature and precipitation results in very wide modeled probability distributions in the predictions of future relative land and water allocation for the major simulated crops (Figure 2). The predictions for some variables do not show significant change at the end-of-century and indicate that given the poor agreement between climate projections, land and water allocation, total crop production, and farm net revenues may increase or decrease in the future with almost equal probability. For example, the probability that land allocated to irrigated barley will change in the future is symmetrically distributed around 0% change.

All in all, our results indicate that without changes in water resource management the Bitterroot River could experience critically low flows during the summer months by the end of the century and a modest increase in water diversions. The effects on producer decision-making and revenues may also be modest, although major impacts cannot be ruled out given climate projection uncertainty. Not only is water from the Bitterroot River vitally important for Ravalli County but also for all downstream water users, including Missoula County. One of Missoula’s largest economic sectors is tourism, most notably the recreational fishing industry, and the Bitterroot River and Clark Fork River are important fisheries for native western cutthroat and the endangered bull trout. The Bitterroot River is also the lifeblood for Ravalli County’s agricultural industry, and producers could experience production declines and net revenue losses. Our goal is that this research can aid in better water resource management to promote a sustainable future for Missoula, Ravalli, and all the counties in Montana.

-- Post by Zachary Lauffenburger

For more information please contact Zachary H. Lauffenburger at zachary1.lauffenburger@umontana.edu or find him on Twitter @zhlauffenburger.

Work Cited:

Whitlock, C., Cross, W., Maxwell, B., Silverman, N., Wade, A., 2017. Montana Climate Assessment. Technical Report. Institute on Ecosystems. Bozeman and Missoula, MT. doi:10.15788/m2ww8w.