COVID-19: An increased threat to people with disabilities living in rural institutions

April 22, 2020

Guest blog post by Dr. Meg Ann Traci, RTC:Rural Knowledge Broker.

While rural America is already known to experience higher rates of health disparities than urban, state and local public health data underscore that the current novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic will continue to harm rural people. COVID-19 is making its way to some of the most rural states of the nation. Just this past week, Alaska’s Kodiak Island Borough had its first diagnosed case of COVID-19 (April 16, 2020); Wyoming experienced its first fatalities (April 15, 2020); and South Dakota is managing 518 cases identified in a meat processing facility (April 17, 2020).

Additionally, local and national news headline stories revealed the increased burden of the virus among residents and workers in group quarters such as prisons, nursing homes, and juvenile group homes (non-correctional). The high rates of infection and deaths at a long term care facility in Kirkland, Washington, caught the nation’s attention and refocused the public health response efforts on institutional settings.

Because people living in institutional settings are more likely to report disabilities than the general population and these settings are not evenly distributed between urban and rural areas across the United States, rural people with disabilities have a lot at stake in efforts to address the pandemic and outbreaks in institutional settings.

U.S. Census Institutional and Non-Institutional Group Quarters

The U.S. Census collects data on people living in all types of living situations, including on people living in group quarters. Group quarters are places where people live or stay in a group living environment located in places or facilities that are owned or managed by an organization providing services.

There are two main group quarter categories in the Census: institutional and non-institutional settings. Institutional settings include correctional facilities for adults and juveniles, skilled-nursing facilities, inpatient hospice facilities, residential schools for people with disabilities, hospitals with patients who have no usual home elsewhere, and mental hospitals and psychiatric units. Non-institutional settings include college/university student housing, military group quarters, emergency and transitional shelters for people experiencing homelessness, group homes for adults, treatment centers for adults, workers group living quarters and Job Corps centers.

The Census collects group quarters data in the American Community Survey (ACS) and in the Decennial Census. The ACS data tell us more about who lives in institutional settings, and the 2010 U.S. Census provides enough responses for us to show reliable estimates for institutional populations in small geographies like rural counties.

In the United States, the overall rate of disability is 13.1% (see the Annual Disability Statistics Compendium). When looking at rates for those in institutional settings, the rates are much higher: rates in correctional facilities (prisons and jails) are 25.2%, and rates in nursing homes are 96.3% (ACS 2018 table S2602).

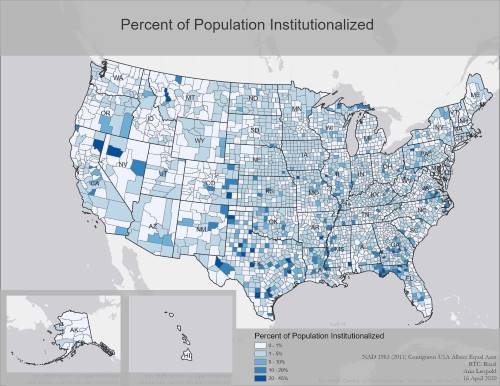

Institutional settings are not spread equally across the U.S.: they tend to be concentrated in rural areas. The following map shows the percent of the population that is institutionalized by county for the entire United States. This map shows the variation in the percent of the population that is institutionalized for each state in the U.S.

There are a number of likely reasons that rural* counties tend to have higher rates of institutionalization than urban (See Table 1 below).

- the relatively recent boom in rural prison infrastructure

- aging trends in rural America

- fewer options in rural areas for home and community-based services, leaving fewer choices to long term care institutional settings

Table 1: Rates of Institutionalized Populations

| Rates of institutionalized populations | |

|---|---|

| Urban | 1.09% |

| Rural | 5.0% |

*We define “rural and urban counties” using the Office of Management and Budget classification; whereas urban = metropolitan counties, and rural = micropolitan and noncore counties.

When we look at the counties with the highest institutional rates in the U.S., all but one in the top ten are rural. (See Table 2).

Table 2: Counties with high rates of institutionalization.

| County Name | Urban/Rural Status | Total Population | Institutionalized | % Institutionalized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowley County, Colorado | Rural | 5,823 | 2,682 | 46.1% |

| Concho County, Texas | Rural | 4,087 | 1,588 | 38.9% |

| West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana | Urban | 15,625 | 5,291 | 33.9% |

| Bent County, Colorado | Rural | 6,499 | 2,149 | 33.1% |

| Garza County, Texas | Rural | 6,461 | 2,096 | 32.4% |

| Forest County, Pennsylvania | Rural | 7,716 | 2,500 | 32.4% |

| Lake County, Tennessee | Rural | 7,832 | 2,506 | 32.0% |

| Union County, Florida | Rural | 15,535 | 4,778 | 30.8% |

| Brown County, Illinois | Rural | 6,937 | 2,110 | 30.4% |

| Greensville County, Virginia | Rural | 12,243 | 3,527 | 28.8% |

Monitoring COVID-19 in Institutional Settings

Though people in institutional settings represent only 2.6% of the national population, they are overrepresented in available reports of those who have, and are dying from, COVID-19 and related illnesses.

Nursing homes and long-term care facilities

Because there is not a national public health surveillance system in place to monitor infectious disease in nursing homes and long term care facilities, news organizations are surveying health departments directly. According to the New York Times (April 21, 2020), nearly 25% of the deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. have been linked to nursing homes and long-term care facilities. There are cases in more than 4,700 nursing homes and long-term care facilities, and over 50,000 residents and staff have contracted the virus. More than 9,000 have died.

Recently, there also are federal efforts underway to advance this public health practice. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released a press release on April 19, 2020 with new regulatory requirements for nursing homes to report COVID-19 cases in their facilities. Cases will be reported to residents, their families and representatives, as well as to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Correctional facilities

Data on the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths among prison and jail inmates are becoming available. The infection rate at the Parnell Correctional Facility in Jackson, Michigan (located about 75 miles west of Detroit) is 10% among prisoners and 21% among staff. The Statesville Correctional Center in Crest Hill, Illinois reports an even higher infection rate of 11% among prisoners. New York City jails collectively report an infection rate of 8%.

Why institutionalized populations are at high risk from COVID-19

The nature of institutional settings makes infection control challenging for a number of reasons. These settings tend to congregate people who, historically, have higher rates of multiple underlying conditions, and who are often supported by staff who are members of the public who rotate through these, and potentially other, institutional care settings in the area. The residents, therefore, are not able to minimize risk exposure as effectively as they might if their support persons were consistent and ideally sheltering-in-place with them.

Social distancing is nearly impossible in institutional settings due to:

- the close living arrangements of residents (with roommates, sleeping in barred and not walled enclosures, eating in communal settings)

- direct care support activities (staff providing support with bathing, toileting, eating, transfers, etc.)

- efficient staffing strategies that support multiple residents across a facility (residents on a whole wing, floor or cell block)

Another risk for those in nursing homes and long-term care facilities: several states are directing hospitals to discharge patients to nursing homes—a practice that is being met with immediate ethical, medical and legal opposition.

Rural institutional settings

The concentration of institutional populations in settings with limited resources to implement infection control plans and maintain quality care makes rural communities and people with disabilities particularly at risk for COVID-19 outbreaks.

The quality of care in nursing homes is assessed on 180 Federal Quality Standards, and it varies across facilities. In rural areas, there are unique challenges to meeting these standards, such as staff shortages (in part because of willingness to drive to nearby urban areas for similar higher paying positions), less access to physicians and specialty care, and geographic isolation.

In general, institutional settings also lack specific resources, including staff with infection control expertise, surveillance systems, staff and visitor policies and related staff training. These limitations are likely more pronounced in rural areas.

In the current COVID-19 emergency, essential resources for the first phases in infection control plans have been lacking. The focus has been on getting personal protective equipment, testing, and treatments to frontline health care providers and other priority populations. These efforts need to be extended across institutional settings to help prevent, identify early, and contain the disease spread, and there needs to be concerted focus on getting these resources to rural areas with the staff, training and implementation supports needed to use these resources effectively.

Strategies for institutional settings

The CDC recently published Five Key Strategies to Prepare for COVID-19 in Long-term Care Facilities (LTCFs). They are:

- Keep COVID-19 from entering your facility

- Identify infections early

- Prevent spread of COVID-19

- Assess supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) and initiate measures to optimize current supply

- Identify and manage severe illness

These strategies can reduce the vulnerabilities of residents in nursing homes and long-term care facilities. However, the staff and resource shortages in rural areas make it more difficult to implement the strategies. Once a staff person introduces the infection to a rural institutional setting, there is less capacity to organize differently or adapt and to mitigate the virus’ ‘wildfire-like’ spread throughout the facility. The need for prevention and controlling spread is of immense importance in these facilities, especially in rural communities where there are limited treatment and healthcare resources, and where there is a greater need to reduce pressure on the health care system.

Other strategies for rural institutional settings include:

- Moves or evacuations to other settings or to the homes of residents’ family members or friends

- ‘Decarcerating’ or releasing prisoners to similar arrangements

The goal of these strategies is to have people in settings that can be maintained with safe living conditions that prevent the virus and can provide appropriate support and care where someone might be or is sick. There are CMS disaster-related policies that can support paid support in alternate settings while maintaining a place in an institutional setting in the future.

A growing number of states are making efforts (e.g., use of strike teams and the National Guard) that were reflected in former Director of Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) Andy Slavitt’s recommendations made in his interview with Rachel Maddow. He advocated for interdisciplinary task force committees with federal government and state and local partners to coordinate three immediate efforts with long term care facilities. Dr. Slavitt’s suggestions also can be applied to support prisons and other institutional settings where people with disabilities live in rural America. His suggestions also are consistent with recommendations formulated from experiences at the COVID-19 outbreak in Kirkland, Washington. A few points are clarified in the related journal article and are included in italics with Dr. Slavitt’s suggestions.

- Get every facility the tests and need resources like personal protective equipment (PPE) and staff training on: a) infection control, symptom screening, and PPE use; b) monitoring residents’ symptoms; c) supporting social distancing, including restricting resident movement and group activities, and restricting visitors and nonessential personnel;

- Help them get to full capacity to meet the current needs, e.g., retrofitting room arrangements, expanding staff and supports to staff, organizing for hospice with more trained nurses—and help them stay at full capacity by identifying and excluding symptomatic workers with active screening programs (i.e., track body temperatures, breathing);

- Be transparent by holding regular phone calls (2-3 times/week) with local, state, and national partners, contribute to and use a data dashboard to track COVID-19 and related issues; and to share challenges and successes—and establishment of plans to address local PPE shortages, including county and state coordination of supply chains and stockpile releases to meet needs. These strategies require coordination and support from public health authorities, partnering health care systems, regulatory agencies, and their respective governing bodies

Concluding Thought

Available data can suggest that pairing the higher rates of people living in institutions reporting disability with higher concentration of institutional settings in rural America presents a need for further diligence of COVID-19 prevention and monitoring efforts.

While the focus of this blog is limited to institutional settings, other congregate care and home and community-based settings need similar attention and access to resources like PPEs, testing, trained staff, and treatment and living arrangement options. Additionally, as more people organize to understand the effects of COVID-19 on residents of institutional settings, there are other outcomes to monitor beyond COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, deaths and recovery and how these may vary across health disparity populations. Examples include data on anxiety and treatments among residents; abuse and neglect; and prolonged stays and rates of institutionalization. It also will be important to understand the impacts on the workers in institutional settings, the health care systems and its workers, and on the communities where the institutions are located. Systems changes also are of interest to monitor and understand moving forward, including the use of community living programs like Money Follows the Person.

Acknowledgements

This guest blog post was written by Meg Ann Traci, Ph.D., University of Montana Research Associate Professor, and Knowledge Broker for RTC:Rural.

The map was created by Arin Leopold, RCT:Rural student research assistant, and Lillie Greiman, RTC: Rural Project Director.