Legal window squeezes prosecutor’s story

By Laura L. Lundquist

Grace Case reporter

People following the trial of W.R. Grace, particularly those in Libby, may wonder why it seems the government has to work so hard to prosecute a case that has played out in civil court several times already. Some question why the defense team for W.R. Grace is able to block seemingly important pieces of evidence.

Often the answers to these questions lie in the narrow scope of the charges filed against the defendant and various time limits that determine what evidence may be used in this trial.

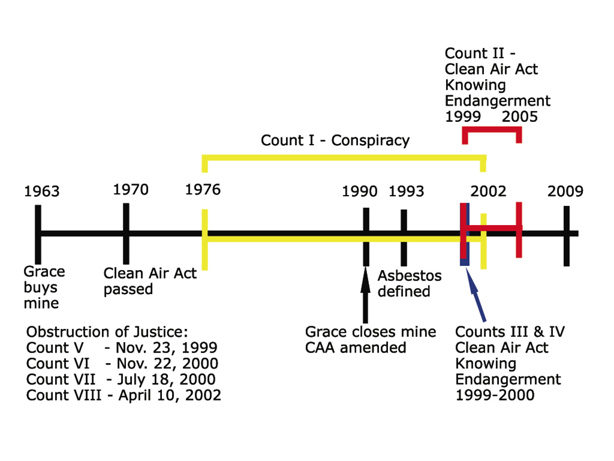

There are eight counts in the indictment against W.R. Grace, and only one has a statute of limitations that includes time prior to 1999.

A statute of limitations is a legally determined window of time that starts when someone supposedly committed an offense. If the statute of limitations is five years, for example, the suspect must be charged within five years of when the crime took place or it didn’t happen as far as the law is concerned. In addition, anything that the suspect did prior to those five years doesn’t count either.

Many defense objections in this trial have occurred when the prosecution has tried to admit a piece of evidence dated before Nov. 3, 1999. Evidence such as a photograph of someone’s child playing in a yard covered with vermiculite in 1997 may seem like it would easily document endangerment, but the defense was able to have it thrown out because of “relevance.”

Nov. 3, 1999, is the cut-off date for all the counts except the first, conspiracy, because the statute of limitations is five years and the charges were essentially filed on Nov. 3, 2004. The judge has allowed evidence to be submitted up through Dec. 5, 2005, creating a window of just six years, one month and three days that is the focus of allowable evidence for all but one of the counts in the trial.

Count II: Basically, the prosecution has to prove that W.R. Grace and the five individual defendants committed some act of knowing endangerment between Nov. 3, 1999 and Feb. 3, 2005, for them to be convicted of violating the Clean Air Act as described by Count II.

Counts III & IV: The time period is shortened to end on June 15, 2000, for endangerment counts III and IV.

Counts V –VIII: The prosecution also has to prove the defendants did certain things during the same time period to justify the four obstruction of justice charges of Counts V through VIII. However, the obstruction of justice charges might be less problematic to prove because each count is associated with a specific incident between 1999 and 2002.

For Count II of knowing endangerment, the prosecutors must show that the defendants released asbestos into the outside air in Libby and Lincoln County and allowed employees to go home covered in asbestos dust. The charge is similar for counts III and IV, but the location of ambient air release of asbestos is focused specifically on the “Screening Plant” and the “Export Plant,” respectively.

The obstruction of justice charges apply only to the corporate defendant, W.R. Grace, and are based upon instances where the company lied to the EPA and denied EPA response teams access to company property.

Except for the count of conspiracy, it doesn’t matter what happened before 1999. Prior to 1999, W.R. Grace could have been belching clouds of toxic gases into the Libby air or could have spent billions on humanitarian effort. Either way, for the purposes of this criminal trial, it is moot.

This frustrates people who claim there is evidence going all the way back to 1963, when Grace bought the Libby mine. Libby resident Mike Crill, a Grace Case blog reader, makes comments along the lines of, “Here, W.R. disGrace knew in 1963 what they were doing and who they were doing this to …”

But the prosecution is not allowed to use the volumes of evidence that they might have collected had the time period of the trial encompassed events as far back as 1963.

Count I: The count of conspiracy allows the prosecution the biggest range of evidence that might be used to argue the case. For that count alone, the prosecution is allowed to reach as far back in time as they have evidence to prove there was a conspiracy to keep the dangers of Libby’s mineral waste a secret from the people of Libby.

The start date ends up being 1976 because that’s the date of the prosecution’s oldest evidence: a study where defendant Henry Eschenbach gathered the health information of 18 retired mine workers and found that 14 had lung disease.

Since conspiracy is usually an on-going crime that criminals try to keep secret, investigators can’t pin down the final date when they know the crime has ended. For all they know, the conspiracy may still be occurring, so when would a statute of limitations time period start? This is why conspiracy evidence can be so old.

But the prosecution must prove that the conspiracy was ongoing during the period that otherwise defines the time limits of the trial. At least one example of at least one defendant doing something to continue the conspiracy must be proven to have occurred within that narrow time period starting Nov. 3, 1999.

Individual defendants could be acquitted on the conspiracy charge if they can raise a doubt about their involvement in the conspiracy by showing they withdrew from the conspiracy before Nov. 3, 1999.

Grace closed its Libby mine in 1990, nine years before Nov. 3, 1999, the start of the time period from which evidence can be presented.

So, the government’s task in prosecuting W.R. Grace may appear tortured to the non-lawyers familiar with events related to the trial. Government attorneys must make their case using evidence that comes only from the narrow window that opened five years before the case was filed – and nine years after Grace closed it’s Libby mine in 1990.

They could have – and judging by the objections to evidence offered, would have — told a different story had the indictment been filed 10 or 15 years earlier.