UM Science Unlocks Secrets of High-Elevation Pregnancies

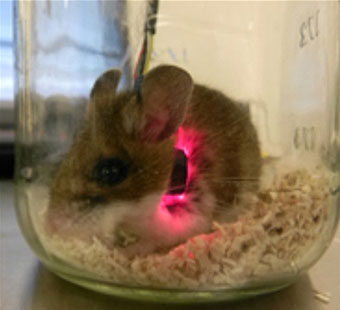

MISSOULA – Pregnancy at high elevations often is associated with low birth weights and other complications. These challenges occur in a wide range of mammals, from deer mice to human beings.

Research conducted at the University of Montana revealed some of the genetic underpinnings that allow certain highland mouse populations to protect developing fetuses in higher areas. The work was published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Understanding how deer mice survive and thrive at high elevations not only informs our understanding of basic evolutionary processes, it may also one day provide clues for treating a range of related disorders in humans,” said Zac Cheviron, a UM researcher and biology associate professor.

The work was led by Kate Wilsterman, a UM postdoctoral researcher who has since joined the faculty of Colorado State University. Cheviron, UM biology Professor Jeff Good and former UM postdoctoral researcher Rena Schweizer were her chief collaborators in Montana.

Their research shows that fetal growth is adversely affected by decreased oxygen at high elevations in mice that are native to low elevations. Mice native to high elevations, however, have genetic differences that provide placental modifications that protect fetuses from hypoxia, which is lack of oxygen to the fetus. This pattern is similar to that observed in humans, such as people of Tibetan or Andean ancestry. These human populations also protect fetal growth at high elevation, but researchers have little understanding of how it is achieved.

Cheviron said one of the most exciting aspects of their work was the discovery that many genes that seem to target fetal growth in their study species – highland deer mice – also have been associated with placental physiology in people.

“This suggests that the genetic and physiological mechanisms that underlie healthy pregnancies at high elevation may have deep evolutionary roots,” he said. “We might be able to use this insight to develop new treatments to improve pregnancy outcomes in humans.”

During the study, lowland mice experienced stunted fetal growth in hypoxia conditions, but highland mice avoided negative effects by altering their placentas.

“If we can understand how deer mice have ‘solved’ the problem of hypoxia for fetal growth,” Wilsterman said, “we may eventually be able to identify targets for treatment development in humans or be in a better position to identify where things are going wrong in gestational diseases that involve hypoxia.”

She said future studies will examine the tissue-level changes they discovered among deer mice. They also hope to identify the genetic variants that contribute to how specific cell types respond to hypoxia.

###

Contact: Zac Cheviron, UM biology associate professor, 406-243-4496, zac.cheviron@mso.umt.edu.