Two UM Researchers Earn Prestigious Early Career NSF Awards

By Cary Shimek, UM News Service

MISSOULA – Doug Brinkerhoff intends to use computer deep learning to improve predictions of sea level rise from melting ice sheets. Beverly Piggott will study how brain cells regulate their own acidity during development.

They are the most recent University of Montana researchers to earn awards from the National Science Foundation’s Faculty Early Career Development Program.

CAREER awards are among NFS’s most prestigious honors, given to promising early career faculty members to provide a foundation for a lifetime of leadership that integrates education with research.

An associate professor of computer science, Dr. Brinkerhoff was awarded $626,000 for a proposal titled “Accelerating Probabilistic Predictions of Sea-Level Rise with Deep Learning.” An assistant professor of neuroscience, Dr. Piggott received $1.1 million for a project called “Bioelectric Mechanisms of Brain Development.”

Brinkerhoff first came to UM in 2007 for an undergraduate degree in geology and then a master’s in computer science. After earning his geophysics doctorate in Alaska, he returned to UM as a faculty member in 2018.

He uses computer code to model the behavior of ice sheets. He said the models he works with are similar to those used to predict the weather but applied to ice rather than the atmosphere. More accurate predictions of ice sheet movement with the world’s warming climate could lead to better expectations for global sea level rise.

However, scientists still don’t completely understand the physics of ice sheets. It’s hard to predict how fast ice will slide over the hidden material it rests upon. There are unknown variables. Brinkerhoff said it’s also expensive running these ice sheet models.

“You could fully flesh out that range of possibilities a lot better with more computation,” he said. “But I can’t run a full-featured ice sheet model for Greenland or Antarctica 1,000 times for 100 years into the future. I don’t have enough computer for that.”

Brinkerhoff will try a workaround to overcome the unknowns and cost. He will train a neural network – a machine-learning algorithm similar to AI – to behave as if it were an ice sheet model. This will involve running the model for shorter periods of time and using mechanisms similar to those used to train language models like ChatGPT, taking in inputs and quickly producing outputs.

“It would operate a whole lot faster than a climate model or ice sheet model would, and hopefully make the same predictions,” he said. “That’s the idea: Replace the physics with a much, much faster approximate neural network. We call it an emulator.”

Will the Greenland ice sheet contribute 1 meter of sea level rise in the next 100 years? Brinkerhoff wants an emulator that will provide the best guess for future decision-makers.

“You are going to make a different decision on how to mitigate sea level rise if the accuracy is plus or minus 10 centimeters versus plus or minus 1 meter,” he said.

Brinkerhoff said his deep learning solution should require less computing power than standard ice sheet models, but he still intends to use UM’s Griz Cluster supercomputer, which was supported by previous CAREER award winner Hilary Martens.

He said much of his grant money will fund graduate students to help with the project. CAREER awards also have an educational component, and he is planning a summer school about the intersection of glaciology and machine learning tools, which will bring 15 students and five instructors from around the world to Montana. They will congregate at a field station near Dillon. The scientists will come from Germany, India, Canada, Taiwan and beyond.

“Hopefully we will build collaborations and come out with a strong scientific community,” Brinkerhoff said. “I’m super excited to bring in this set of young scientists who are prepared to use these new tools for climate predictions.”

The other CAREER winner, Piggott, studies the bioelectrical properties of neural stem cells. Bioelectricity is well known for its role to help neurons fire and muscles contract. It is produced by electrolytes (also known as ions like sodium and potassium) fluxing between cell membranes. Proteins called ion channels regulate these fluxes. Problems or mutations in ion channels can cause neurodevelopmental disorders.

Stem cells develop into other cells. In humans, neural stem cells are thought to exist primarily during early stages of development. Piggott said neural stem cells can divide many times, generating the large numbers of neurons needed to create a functional brain. When she and her research team examined the pH of the developing cells, they discovered that neurons are more acidic than the stem cells from which they originate.

“We have no idea why this might be the case,” she said. “So my proposal was to try to understand why neural stem cells and neurons regulate their pH and whether that facilitates how they work. Can a specific pH level help them perform their functions?”

A Wisconsin native, Piggott earned her Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, where she examined how neural circuits generate behavior. She then obtained a Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellowship to work in the renowned Jan Lab at the University of California San Francisco.

During her postdoctoral work, she discovered a novel role for “voltage-gated sodium channels in regulating neural progenitors [cells that give rise to neurons] during brain formation.” These ion channel proteins are opened by voltage, which allows a rapid flow of sodium to enter cells. They are best known for regulating neural firing, so a role for them in stem cell lineages was surprising.

Humans have nine of these channels and fruit flies have one, making them a more straightforward model to understand the biological function of the channels in cell types.

“With this grant, we are using a fruit fly model to study pH in neural stem cells,” Piggott said. “Some of the first ion channels were originally discovered in fruit flies, and research into this model helped us identify fundamental principles of how neural progenitors build a brain. By using this well described system, we can identify the proteins that drive distinct pH changes between neural progenitors and neurons and understand how pH state impacts cell behavior.”

She said unusual pH readings in the brain are associated with several different human maladies such as Christianson Syndrome, Huntington’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Autism spectrum disorders and seizures.

“If we understand the mechanisms by which cells regulate pH, we might be able to identify new therapeutic targets to treat pH dysfunction in various neurological disorders,” she said.

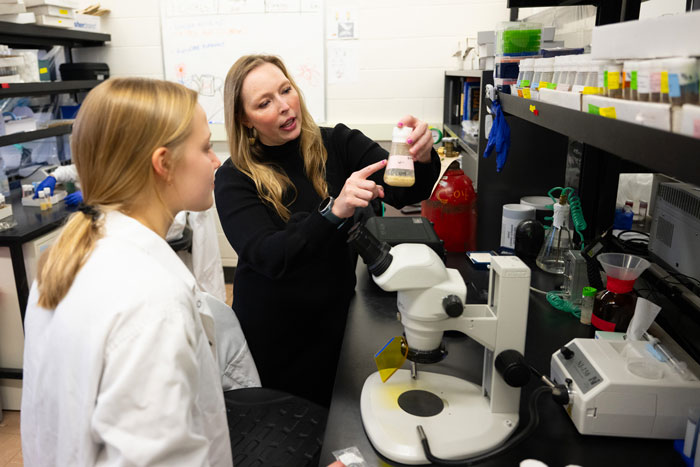

Piggott joined UM in 2020. She said the grant will provide stability to her lab, which now employs six people, including two graduate students, three undergraduate neuroscience majors and a research technician, who began working in the lab as an UM undergraduate before becoming a permanent employee.

“I was thrilled to receive this award, as it indicates experts in the field appreciate the significance of our studies,” she said.

As part of the education and research component of her CAREER grant, Piggott will introduce a Developmental Neuroscience Research course, which will allow UM students to work with her to investigate electrical properties of neural stem cell development. Additionally, she will develop a new K-12 exhibit for UM’s spectrUM Discovery Area at the Missoula Library that will demonstrate how fruit fly models can be used to study neurological diseases.

“Hopefully it will make the science come alive for the students,” she said.

###

Contact: Doug Brinkerhoff, UM associate professor of computer science, 406-243-2883, doug.brinkerhoff@mso.umt.edu; Beverly Piggott, UM assistant professor of neuroscience, 406-243-2668, beverly.piggott@mso.umt.edu.