USDA-NIFA Water for Agriculture

Research Grant:

2016-67026-25067

NSF EPSCoRNSF EPSCoR

Cooperative Agreement:

#EPS-1101342

Montana NASA EPSCoR

Research Grant:

80NSSC18M0025M

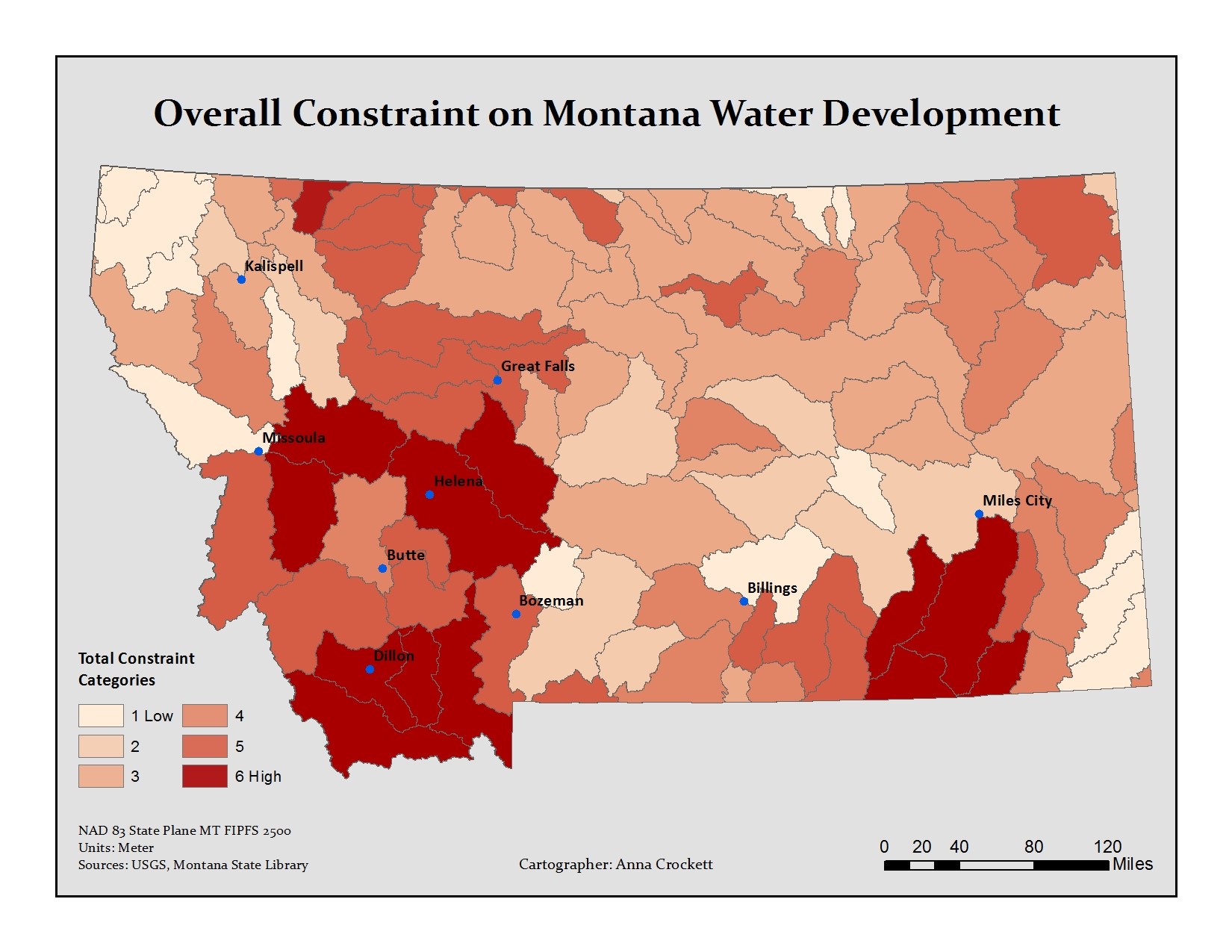

This analysis establishes that 13% and 33% or one-third of HUC-8 watersheds in the state have high to medium-high levels of legal constraints to water use, respectively. These legal constraints can translate into decreased flexibility for producers and water managers to change water uses or develop new sources of water under periods of increased hydrologic variability, including drought. The spatial pattern of these highly constrained areas is also important to note. Watersheds with high legal constraints are generally rural, but contain parts of counties with the highest populations and population densities and contain or are upstream of the main urban centers of the state. This result is not surprising even though withdrawals for public water supply only account for 1.8% of all water withdrawn from surface and groundwater sources in Montana annually (Maupin et al. 2010). Of the six constraining aspects of water law and policy, many of these tend to overlap around urban and peri-urban areas. For example, whereas surface water allocations play the biggest role in constraining water use in NE Montana, in SW Montana, surface water allocations combine with groundwater restrictions, instream flow rights, and increased water quality regulation on impaired stream segments in order to raise the overall level of legal constraints in these watersheds. Surface water allocations and groundwater restrictions were the most influential legal constraints to water use and development measured in this analysis, but in certain watersheds, other legal drivers were particularly important because they constrained the geographic scope of the entire watershed (e.g., the Blackfeet Water Compact in NW Montana and water quality regulations in the Bighorn River Basin of SE Montana).

This analysis is but a first step toward integrating legal and institutional constraints to water use with biophysical data on water availability and agricultural production. We hope that by using this information, agency hydrologists and water managers, agricultural industry planners and water users can (1) more accurately examine water availability under future scenarios and identify areas of potential adaptive capacity across the state; and (2) design more effective policies including incentives that create flexibility for water management in the most vulnerable areas, i.e. watersheds that are both legally constrained and have increasing sensitivity to hydrologic changes.

Please contact Brian Chaffin with any questions.

References:

Maupin MA, Kenny JF, Hutson SS, Lovelace JK, Barber NL, Linsey KS. 2010. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2010. USGS Circular 1405. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Reston, VA.