Appendix: The University of Montana’s Academic Future: A guiding document for Academic Affairs

Higher education is experiencing a watershed moment across the United States. Shifting student and societal needs, changing demographics (Grawe 2018; 2021), and the lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have all created unprecedented financial pressures that require colleges and universities of all types to redefine the inherent value of higher education in the face of new public mindsets and student expectations. Colleges and universities across the country are facing budgetary shortfalls and associated cuts. The institutions that survive, and in some cases thrive, will make long overdue innovations to both preserve and refresh the promise of higher education and move the higher education ecosystem in new directions. The University of Montana (UM) has the opportunity to both take advantage of – and serve exceptionally well – students who will be part of regional demographic trends which signal population growth in the West and increasing racial and ethnic diversity (Seltzer 2020; Grawe 2021, p. 52, 68).

To succeed as a flagship for the future that draws upon its enviable location, UM must adapt its portfolio of degree and curricular offerings to offer flexibility with both breadth and depth, including relevant interdisciplinary and experiential learning pathways that are centered on student needs and are recognized by students, parents, and employers as leading to strong post-graduate outcomes. We should embrace and cultivate our “dual identity” as a university with a strong liberal arts tradition that pairs with multiple strong graduate and professional programs. Likewise, we must embrace and take seriously the need to make a sustained commitment to serving students from all backgrounds, races and ethnicities, and recognize that doing so requires comprehensive changes and meaningful investments. And, we must help UM students cultivate a tolerance for ambiguity and understand the complex interdependencies in a rapidly changing world. Our guiding purpose in supporting students includes providing timeless values and essential relevant skills so that the student of today can become an engaged and productive member of society tomorrow.

To that end, President Bodnar highlights the need for UM to combine its notable strengths in the liberal arts with experiential learning opportunities and co-curricular career skills development, leading to post-graduate success in today’s complex world. Last fall, the President presented UM’s academic leaders with the following charge:

Adapt our curricular and academic approach to more intentionally and explicitly build in our students foundational competencies such as problem-solving, critical thinking, information and data literacy, teamwork, leadership, creativity, and innovation; and integrate significant experiential and work-based learning opportunities throughout every student’s experience, ensuring all students have skills necessary for success in a competitive, dynamic job market.

How do we do this? First, we reject the mistaken notion that a focus on student outcomes and career preparedness somehow threatens to diminish a strong foundation in the liberal arts; on the contrary, these concepts are intimately entwined. There is abundant evidence that both employers and graduate schools seek students with a liberal arts foundation grounded in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences (Pasquerella 2019). An effective liberal arts education, where students learn to view issues with a critical and curious mindset from multiple angles, prepares them for the wide variety of career opportunities they will likely encounter in their lifetimes. Employers and graduate schools seek graduates who bring hands-on, real-world experiences that demonstrate the application of foundational knowledge and skills in a wide range of settings.

Over the past decade, the World Economic Forum list of top ten critical job skills has changed markedly to stress competencies a liberal arts education can provide, such as analytical thinking and innovation, creative problem-solving, and resilience, to name a few (Whiting 2020). In fact, many institutions across the country are embracing the liberal arts, including top military academies like West Point, as well as other institutions like Northeastern University, which has developed an Experiential Academics program within their College of Humanities and Social Sciences that includes the pillars of cooperative education, undergraduate research, study abroad, and service learning combined with the rigorous study of society, culture, politics, and ethics (“Experiential Academics” 2021). When intentional and facilitated professional and experiential training are combined with a liberal arts foundation, graduates are better positioned to work effectively in diverse teams that must contend with ambiguity and complexity (Aoun 2018). Again, UM’s considerable strengths in several professional school realms is an asset here: those programs can help provide opportunities and insight for the university’s liberal arts core, while drawing and learning from that core themselves.

Like Northeastern University, the University of Southern California (USC)’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences is a good recent example of seeking such a fusion and re-imagining what a liberal arts core might look like. (“USC Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences” 2021). Recognizing the changing demographics and needs of today’s students, USC Dornsife developed a complete overhaul of the student experience (McGroarty 2021). Key components include:

- A revamped curriculum that includes numerous interdisciplinary degree offerings (“Majors and Minors” 2021);

- A reimagined first-year experience (“USC Core” 2021);

- The Dornsife Toolkit (“Dornsife Toolkit” 2021); and

- A collection of 2-credit classes that incorporate intellectual and practical skills that are typically acquired through work and life experience.

This holistic educational experience is best summarized by USC with their slogan, “Earning your undergraduate degree at USC Dornsife is the difference between a good education and a life-changing experience.” We see this as a model that could be successfully implemented at UM at a smaller scale, as it is grounded in components that are already present at UM: broad-based interdisciplinary liberal arts education supported by student support services, with both experiential learning and career readiness opportunities embedded in the curriculum.

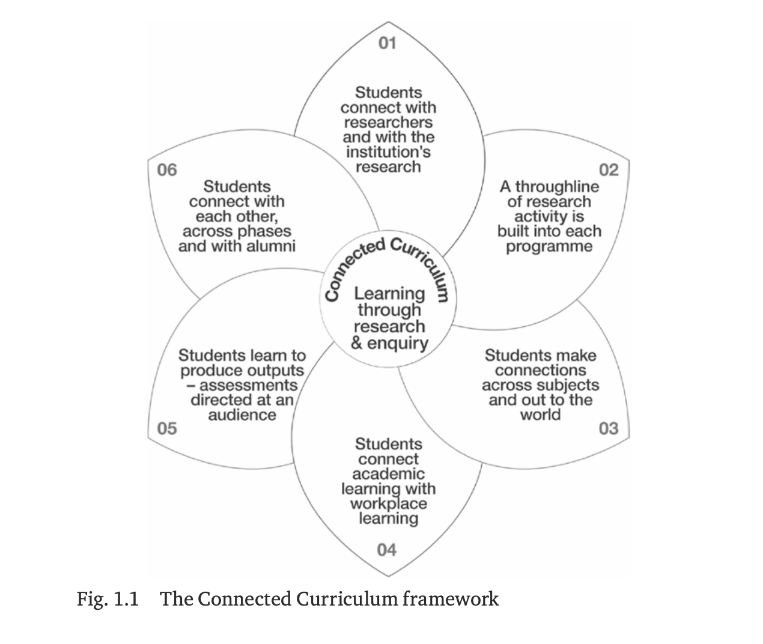

USC’s Dornsife College is an example that buttresses the work of the University Design Team (UDT), most notably through the UDT’s design principles and its study of A Connected Curriculum (Fung 2017). The design principles developed by the UDT derive from and are consistent with the group’s research, which shows that to prepare students for success after college in an ever-changing society, universities must develop a curriculum that is interdisciplinary, student-centered, and in which students do extended research and have significant opportunities for experiential learning. The design principles emphasize impact, inquiry, innovation, internationalization, inclusivity, and interdisciplinarity as guideposts for UM’s future. The UDT has offered a possible model for how the design principles could be implemented and advanced: the Connected Curriculum, first articulated by Professor Dilly Fung at the University College of London. The Connected Curriculum is grounded in the science of learning and centers on the long-standing—but often not truly implemented—notion of undergraduate education driven by interdisciplinary inquiry, with close integration of research and creative work. The overarching concept is presented graphically in the figure below, adapted from Professor Fung’s book. The approach has been successfully adopted and implemented at University College London and University College Cork, both of which are international leaders in higher education that is research intensive and experientially grounded.

Even with the Dornsife College and Connected Curriculum models, general education (Gen Ed) persists as a widespread challenge throughout higher education. And yet, Gen Ed represents an invaluable opportunity to apply concepts such as those in the Connected Curriculum. The institutions that have embraced bolder, more experiential and more interdisciplinary approaches to Gen Ed (e.g., USC’s Dornsife Core described above, Goucher College, Ripon College, College of William and Mary, Northern Illinois University, Virginia Tech, and the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, to name a few) have seen strong increases in student satisfaction such that their ability to attract and retain students improves substantially. UM can become one of those institutions. This would require us to change both our philosophical and fiscal approaches to our educational core. It would mean eliminating obstructive fiscal incentives which lead to an overabundance of Gen Ed courses, and redesigning the core curriculum to focus on the kinds of highly integrated, deeply experiential approaches students seek and employers value.

Despite the challenges of the last decade, UM boasts many of the strengths necessary to become an institution that is known for the quality of the undergraduate experience, such that it attracts and retains students. Data from prospective students show that compared to peer institutions, UM’s size is an advantage—it allows students to access a flagship university’s wide range of academic and social opportunities while engaging in classes, co-curricular opportunities and other educational modalities that allow for more intimate and tailored time with peers and professors. Most state universities cannot provide this ‘big yet small’ experience; UM can and does.

Experiential education, typically defined to include internships, undergraduate research, study abroad, and service learning, can be offered to all students at ‘big yet small’ institutions like UM. Fortunately, UM already has a strong tradition of providing experiential education opportunities to students in all of its colleges; in the past, the administration has identified student engagement in experiential learning as part of UM’s institutional goals (UM institutional assessment reports 2013-2015). There is ample opportunity to embed existing and new experiential learning opportunities in the curriculum for every UM undergraduate. The combination of experiential learning with a strong liberal arts foundation provides opportunities for synergies at a scale other universities cannot match.

We must approach this ideal in a way that ensures all students have access to experiential learning opportunities – and recognize that the ways in which students experience any curriculum, but perhaps especially deep-dive, experiential ones, is shaped by their socio-economic backgrounds. Experiential education must be guided strongly by the principles of inclusive pedagogy, and that includes recognizing the economic barriers to some critical experiences. For example, lower income students are often not able to afford an unpaid internship, and in higher education – as with the country as a whole – students with fewer economic resources and choices are disproportionately coming from BIPOC communities. Determining how to incorporate high-quality experiential learning opportunities while maintaining an equitable playing field for students is an essential challenge to address.

Success in carrying out any of our educational goals requires deliberate design for the outcomes we want. On the undergraduate front, recent market research indicates that UM has at least three significant challenges to overcome. Two are entwined with the academic enterprise: prospective students value academic quality and strong post-graduate outcomes. The third relates to prospective students and families favoring universities that offer a vibrant campus life. We are taking the market research and data provided by prospective students seriously – and to those three we add the overarching need to design our future with a comprehensive commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion.

This all means we must be willing to change the ways in which we deliver undergraduate education at UM. That is not a knock on our past or present; it is simply a recognition of the rapidly changing world and the moral, educational and fiscal imperatives we now face. All of our undergraduate programs need to use flexible and adaptable curricula, combined with intentional experiential learning and career readiness experiences to build on our strengths and improve our academic offerings and quality, thus improving perceptions and UM’s overall reputation. We should work toward presenting a diversity of offerings that encompass both the best of the liberal arts, as well as the more prescribed curricula of the professional colleges and schools.

The latter bears more explicit mention. While UM has seen a notable decline in undergraduate enrollment over the past decade, some portions of the campus bucked this trend, and demonstrate both areas of growing need and opportunity as well as models that might be broadly applicable across campus. Put most broadly, we are a comprehensive university, one that already serves a wide range of learners and needs, and that should be seen as an asset. From law to business, to health and medicine, to forestry and conservation, UM has seen multiple areas of stability or even notable growth amidst an overall challenging period. Likewise, our research enterprise has grown remarkably over the past decade, in turn expanding opportunities in both graduate education and the ways in which UM can serve its broad array of stakeholders. At times, these multiple dimensions of a comprehensive university can be seen as in conflict and create internal tensions, but they should be viewed as a strength which helps UM adapt to a shifting landscape in which student and societal demands are changing.

In thinking about paths to innovation, the University must leverage a key existing strength: its diverse and growing graduate student population, which makes up more than a quarter of current UM students. Graduate programs already enact many of the core principles articulated in this document, including innovation in interdisciplinary research and education, as well as degree outcomes with a significant impact on the local, state, regional, and international communities. Our professional programs contribute significant expertise to the state and region, while generating revenue for the institution. Our MFA programs carry the University’s creative mission to the public through theater, musical performance, and published works that extend our University’s reputation throughout the world in the form of Pulitzer Prize-winning graduates. Our academic disciplines at both the Masters and Doctoral levels create new knowledge and consolidate received wisdom, while building out the intellectual infrastructure of our society, and cementing core values of civic society. Our graduate students in research disciplines funded by grants contribute directly to our annual research expenditure of $110m by expanding our research capacity, which has been the primary contributor to obtaining performance funding from the state.

All of those positive impacts contribute directly to the undergraduate experience, especially in the ‘big yet small’ context: undergraduate students work in labs with graduate students, who mentor them in formal and informal ways, while providing role models for future success beyond their undergraduate degrees. Graduate students also teach many lower-division courses, and open up paths to cutting-edge ideas in a range of fields that cultivate student ambition. This graduate student population is a major asset to the University, in which we must continue to invest, and with which we can continue to innovate, especially in interdisciplinary fields. Decisions about steps ahead thus need to attend closely to the specific needs of graduate education, which in some areas can operate in higher faculty-student ratios (distance education, some forms of professional education with larger cohorts), but in many programs requires smaller ratios. Investment in graduate programs pays off by cultivating a high standard of excellence in research, creativity, and professional growth that radiates in positive ways to the larger undergraduate student population. Graduate education should be a core component of what we communicate to the public about the capacities and values of a state-funded institution of higher education.

To that end, UM should continue to actively develop an increasingly broad portfolio of learning modalities, from online delivery of “traditional” courses, to a range of both digital and in person offerings that can serve learners who are not seeking a four-year degree. Again, our location and the associated connections and expertise it brings provides clear opportunities here, some of which are already being realized. These can range from micro-credentials to full blown graduate degrees, and even offerings that don’t fall cleanly into any of these categories but draw from unique combinations of faculty expertise and demand. The key is to make sure there are structures and incentives in place that both help identify the opportunities and provide means by which faculty can engage in them. As with most areas stressed in this document, there are already excellent examples to be found across campus that demonstrate the potential. The challenge is often found in scaling up new modalities while continuing to meet the demands of existing programs.

Given UM’s existing strengths and context as well as national trends in the higher education landscape, we see a future for UM in which we make changes that accomplish seven goals:

- Offer more opportunities for breadth (i.e., interdisciplinary degrees) while maintaining depth in strategic areas and diversity in our degree offerings.

- Reimagine the first-year and Gen Ed experience to give students the opportunity to study real-world problems through an applied and interdisciplinary lens. The curriculum needs to appeal to student interests, which will improve students’ perceptions of the academic quality of their UM experience.

- Build intentional experiential learning paths (internships, undergraduate research, study abroad, and service learning) throughout each degree in ways that emphasize our unique ‘big yet small’ potential.

- Embrace and support strengths in graduate and professional education, and facilitate ways in which those are better integrated with an evolving residential undergraduate program.

- Improve perceptions of post-graduate outcomes by investing in alumni relations, strengthening ties to our recent graduates and using their success stories to strategically promote the UM undergraduate experience.

- Create budgetary pathways and incentives which expand our learner base, from online course and degree options, to a range of shorter-format offerings.

- Make justice, equity, diversity and inclusion a core principle that guides our entire academic enterprise.

Finally, to achieve such goals, we stress two points. One, as noted above, there are multiple examples of excellent and creative faculty efforts across campus that speak directly to the main goals of this document. In many cases, they simply need more targeted support, as well as mechanisms that best support the cross-fertilization of successful models so that good ideas can take root and flourish more broadly. Second, we emphasize the need for a “One UM” philosophy, in which the diverse components of our academic mission are seen as a strength, and in which inevitable shifts in student interest and demand across those areas over time do not become a force which divides us. Indeed, we are fortunate to have this broad base from which to respond to an educational environment that is undergoing substantial disruption. By working together, and embracing a willingness to change quickly and flexibly, the institution as a whole is best poised to succeed.

Principal contributors: Adrea Lawrence, Dean of the Phyllis J. Washington College of Education, Larry Hufford, former Dean of the College of Humanities and Sciences, Alan Townsend, Dean of the W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, and Ashby Kinch, Professor and Associate Dean of the Graduate School.