X.7 Nondiscrimination in Education

No religious or partisan test or qualification shall be required of any teacher or student as a condition of admission into any public educational institution. Attendance shall not be required at any religious service. No sectarian tenets shall be advocated in any public educational institution of the state. No person shall be refused admission to any public educational institution on account of sex, race, creed, religion, political beliefs, or national origin.

History

Sources

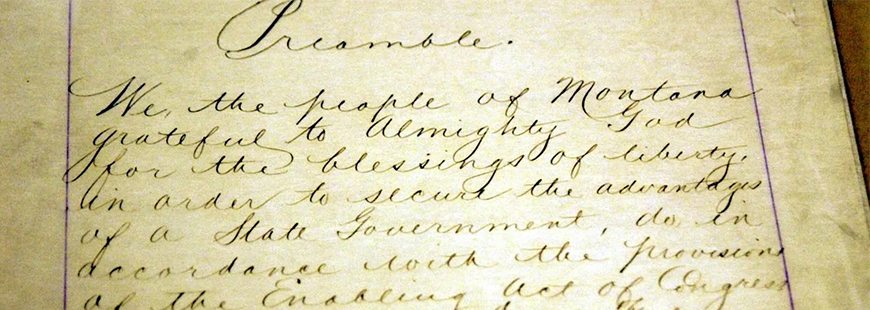

1884 Montana Constitution (proposed)

Article IX, Section 7. The public free schools of the State shall be open to all children and youth between the ages of five and twenty-one years.

Wiki Author's Analysis: Although Article IX, Section 7 of the proposed 1884 Constitution was omitted by subsequent Constitutions, it nevertheless reflects Montanans' longstanding intent that the State's schools be open to all and free from discrimination. For example, in an address to Montana voters, infra, the 1884 Constitutional Convention emphasized that the Constitution's Education provision opens school doors "unconditionally" to all ages, regardless of creed or political party.

Article IX, Section 10. No religious or partisan test or qualification shall ever be required of any person as a condition of admission into any public educational institution of the State, either as teacher or student; nor shall attendance be required at any religious service whatever, nor shall any sectarian tenets be taught in any public educational institution of the State; nor shall any person be debarred admission to any of the collegiate departments of the University on account of sex.

1889 Montana Constitution

Article XI, Section 9. No religious or partisan test or qualification shall ever be required of any person as a condition of admission to any public educational institution of the State, either as teacher or student; nor shall attendance be required at any religious service whatever, nor shall any sectarian tenets be taught in any public educational institution of the State; nor shall any person be debarred admission to any of the collegiate departments of the university on account of sex.

Other Sources

- 1884 Montana Constitution, An Address to the Voters of the Territory of MontanaMont. Const. Conv. Comm'n., Mont. Const. Conv. Occasional Paper No. 1: Mont. Const. of 1884 52 (1971–1972).

"Education. No State Constitution has made better educational provisions than the one we present for your candid consideration. The experience of mankind has demonstrated that the happiness, prosperity and permanency of a country is measured by the intelligence of its people. No surer or better means for the dissemination of knowledge among all classes of society has ever been devised than the one here presented. This Constitution commits the State fully and unequivocally to the perpetual maintenance of public free schools; opens the school doors unconditionally to the admission of all ages between the ages of five and twenty-one years . . . No stronger guarantees could have been devised than are contained in this Constitution to prevent our schools of every grade from falling into the hands or under the influence of any sect or creed, or political party."

Wiki Author's Analysis: It is notable here that the 1884 Constitutional Convention, in explaining its goals for the State's educational institutions to voters, emphasizes protection from political and religious discrimination, but does not address discrimination based on sex or race. While sex discrimination made it into the text of all three versions of this provision, racial and other forms of discrimination would be absent until 1972.

- Elbert F. Allen, Sources of the Montana State Constitution (June 10, 1910)Mont. Const. Conv. Comm'n., Rsch. Memorandum No. 4, 5 (1971–1972).

"In general. By far the larger part of our constitution was taken directly from that of Colorado, some from California and less amount from other states."

Wiki Author's Analysis: Based on Allen's comments, relevant provisions from the Colorado and California Constitutions are provided below. The two states adopted their respective Constitutions prior to the proposal of the 1884 Montana Constitution. Therefore, it is probable that the drafters would have used California and Colorado's models when they drafted the Montana analogue.

"Article XI, 1889 Montana Constitution. Article eleven, Education, is not based on any other single constitution, although undoubtedly most of the sections were based on already existing school laws; probably the constitutions of Cal., Colo., Kan. and Minn., but we have been unable to get any information which would justify us in making any definite statement. Sec. 11 was probably original with the committee and was prompted by the unsatisfactory provisions of other states, Mr. A.J. Craven mentions Iowa in particular."

Wiki Author's Analysis: A review of the 1857 Iowa Constitution, to which Allen probably alludes, reveals no similar provision to Montana's nondiscrimination in education provision.

- 1876 Colorado ConstitutionColo. Const. art. IX, sec. 8 (1876) (available at https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/CO_Constitution_150dpi_Signed.pdf).

Article IX, Sec. 8. No religious test or qualification shall ever be required for any person as a condition of admission into any public educational institution of the State, either as teacher or student; and no teacher or student of any such institution shall ever be required to attend, or participate in any religious service whatever. No sectarian tenets or doctrines shall ever be taught in the public schools, nor shall any distinction or classification of pupils be made on account of race or color.

- 1879 California ConstitutionCal. Const. art. IX, sec. 8 (1879) (available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c025463003;view=1up;seq=134).

Article IX, Sec. 8. No Public Money for Sectarian Schools. No public money shall ever be appropriated for the support of any sectarian or denominational school, or any school not under the exclusive control of the officers of the public schools; nor shall any sectarian or denominational doctrine be taught, or instruction thereon be permitted, directly or indirectly, in any of the common schools of this State.

Montana Constitutional Convention Commission

- Comparison with the Constitutions of Other StatesMont. Const. Conv. Comm'n., Mont. Const. Conv. Occasional Paper No. 5: Comparison of the Montana Constitution with the Constitutions of Selected Other States XI, 9 (1971–1972).

Wiki Author's Introduction: In an effort to provide the 1972 Constitutional Convention Delegates with information about the previous versions of the Montana Constitution, the Convention Commission published a series of research papers. Here, the Commission compared Montana's 1889 constitutional provisions to those of other states. The Commission did not compare Montana's nondiscrimination in education provision to California or Colorado's Constitutions, discussed supra.

"COMMENT: This section is identical to Section 10, Article IX of the 1884 Constitution. Section 9 has never been amended nor have any amendments been proposed to alter its 1889 wording.

ALASKA: No comparable section in Article VII.

HAWAII: No comparable section in Article IX.

MICHIGAN: No comparable section in Article VIII.

NEW JERSEY: No comparable section in Article VIII.

PUERTO RICO: No comparable section in Article II.

MODEL STATE CONSTITUTION: No comparable section in Article IX."

- 1968 Legislative Council Report on the Montana ConstitutionMont. Const. Conv. Comm'n., Mont. Const. Conv. Occasional Paper No. 6: 1968 Legislative Council Report on the Montana Constitution Ch. XII, 54 (1971–1972).

"COMMENT: None of the six constitutions used for comparative purposes have similar provisions. The Council concludes, however, that this section is adequate."

- Constitutional Provisions Proposed by Constitution Revision Commission Subcommittees Mont. Const. Conv. Comm'n., Mont. Const. Conv. Occasional Paper No. 7: Constitutional Provisions Proposed by Constitution Revision Commission Subcommittees 184 (1971–1972).

"Comment: The subcommittee recommends that this section be retained, although it may be unnecessary because of the first amendment, religious and equal protection freedoms of the United States and Montana Constitutions."

Wiki Author's Analysis: This Comment foreshadows concerns voiced by a Delegate during the 1972 Constitutional Convention, discussed infra. That is: whether Article X, Section 7 is an unnecessary redundancy in light of the right to dignity and protection from discrimination found in Article II, Section 4 of the 1972 Constitution.

Drafting

Education and Public Lands Committee Proposal: Reported February 22, 1972Mont. Const. Conv., Comm. Report, Vol. II 730–31.

Wiki Author's Introduction: The Education Committee's comments preview concerns that would be ultimately fleshed out by the body of the Convention during floor debates. For its pat, the Committee viewed Article X, Section 7 not as an unnecessary iteration of guarantees provided in the Bill of Rights, but as a necessary specification for teachers and students in the public educational institutions. Additionally, prior to the floor debate, the Committee attempted to clarify that the provision would not ban objective learning about religious principles. Nevertheless, the Committee members would ultimately be called upon to explain this distinction on the Convention floor.

Proposed Text

Section 7. NON-DISCRIMINATION IN EDUCTION. No religious or partisan test or qualification shall ever be required of any person as a condition of admission into any public educational institution of the state, either as teacher or student; nor shall attendance be required at any religious service whatever, nor shall any sectarian tenets be taught in any public educational institution of the state; nor shall any person be debarred admission to any public institution of learning on account of sex, race, creed, religion, or national origin.

Comments

"This section is a broadened version of the present section 9. A statement specifically banning discriminatory practices in education provides a necessary specification with respect to teachers and students of nondiscrimination principles broadly articulated in the Bill of Rights. The committee feels that the principle set forth in the last sentence of the present section i.e., 'nor shall any person be debarred admission to any of the collegiate departments of the university on account of sex,' represents an arbitrary limitation on the general principle of nondiscrimination in admission policies. The committee has therefore broadened the language to include all public educational institutions under the protection of the provision and to prohibit other kinds of possible discrimination.

The committee also considered carefully the language of the phrase, 'nor shall any sectarian tenets be taught in any public educational institution,' and decided against any change in wording. There has been no record of difficulty in the interpretation of the meaning of this provision, which clearly is not intended to restrict objective learning about religious principles, but rather to prohibit the active promotion in a public school of religion or of any particular religious doctrine. The existing language adequately expresses this principle."

Debate: March 11, 1972Mont. Const. Conv., Verbatim Trans. 2031–45, Mar. 11, 1972.

Wiki Author's Introduction: The following section contains excerpts from the verbatim transcript recorded during the 1972 Constitutional Convention. It has been divided into subsections based on issue.

Meaning of "Qualification"

Wiki Author's Introduction: Over the concerns of Delegates Bugbee and Dahood, Education Committee Chairs Champoux and Noble, with the support of Convention President Graybill, iterated that the only qualifications with which the provision is concerned are political and religious. And, the provision's supporters pointed out that any ambiguity found in the word "qualification" had never been brought to bear in Montana's courts in nearly a century (nor has it since).

- Delegate Noble: "I think it's self-explanatory. It's about like the old Constitution, with the addition of 'race, creed' and 'religion or national origin.' Other than that, it's the same as what we have."

- Delegate Harlow: "Mr. Chairman. I merely move-- or rise for a bit of discussion and clarification in regard to this section it referred to as the nondiscrimination section. And it states that no qualification, along with the other words, shall be required to attend school. It has disturbed me over the years-- and particularly in the later years, but over the years-- that school boards will set up some arbitrary qualifications that a student must meet before they can attend school. Quite a few years ago, when the styles of ladies' dresses were coming higher, the Glasgow School Board said that the girls could not come to school if they wore stylish dresses. Just lately, we had a case that's been brought clear to the courts, both in Hamilton and in Columbia Falls, in which the school board arbitrarily set up a requirement on how often you were supposed to get a haircut. And the court upheld the student in Hamilton. He could not go to school because his hair was a little bit long-- similarly applied to the students in Columbia Falls. Now, I would like to know if this word 'qualification' in the Constitution would prohibit such actions by school boards. And if this word has been in here as it is said and as I will agree to-- then what right has the Supreme Court or-- this didn't go to the Supreme Court; I think it may. But the local courts can state that school boards can set up qualifications before a student is allowed to come to school. Now, the-- I'm perfectly willing to accept the fact that maybe some qualifications as to health might debar the student from coming to school, if it's a contagious disease or something along that particular line-- he might want to come to school. But I would like to get some opinions from the various judicial lines here, if this word will restrict and make school boards allow students to come to school where they are properly dressed and hair length and various other things."

- Delegate Davis: "Mr. President. As a member of the majority on this, it's my understanding that that has been interpreted only as saying 'no religious or partisan test or qualification.' I think it refers only to the religious or partisan test or qualification and doesn't go into these other matters in this Constitution. I think that's the reason why that has not been a factor in determining these, as near I know, Mr. Harlow."

- Delegate Bugbee: "...You talked previously about the word "qualification.'"

- Delegate Champoux: "Yes."

- Delegate Bugbee: "You think there's no problem there?"

- Delegate Champoux: "I wouldn't say that. What I'm basing my conclusion on is the past record of the courts. That's all I'm basing it on. I think Mr. Davis would substantiate me on that, that we haven't had any problems on that. Whether we will in the future, who knows?"

- Delegate Bugbee: "Delegate Dahood, what's your opinion of that word?"

- Delegate Dahood: "I'm bothered by the word 'qualification.' I suppose somebody could use it in a way in which it's not intended. I regret that Delegate Foster's amendment didn't carry, and then perhaps we could have gone back to the word 'qualification'-- had something that's going to carry out our intent. But I could see where someone could cause some problem with respect to 'qualification.'"

- Chairman Graybill: "Mrs. Bugbee and Mr. Dahood. May the Chair observe that Mr. Davis explained at the beginning of this, and I think it's not an unreasonable explanation, that the word 'qualification' is modified by 'religious' and 'partisan.' It's religious qualification and partisan qualifications which the Constitution has been held so far to prescribe [sic]. Now, if you want to take it out of there, fine, but that's Mr. Davis' explanation."

- Delegate Davis: "Mr. President. This was placed in the Constitution in 1889. We've never had a case come up on it yet. Now, maybe we can change it and do better than they've done the last 80-some years, but I have some serious doubts. I also told the constituents in my area that I was going to try to leave some of the things in that worked for about 80 or 90 years without causing any problems. So I support the majority to leave it like it is."

Meaning of "Sectarian Tenets"

Wiki Author's Introduction: As predicted by the Education Committee, Delegates on the floor expressed concern about the distinction between teaching religion for objective educational purposes and advocating religious doctrines. Delegate Burkhardt explained that nothing in Article X, Section 7 would act to prevent schools from objectively educating students about various religious principles. Nevertheless, the provision was ultimately revised to prohibit advocacy of sectarian tenets, rather than that sectarian tenets must not be "taught."

- Delegate Bugbee: "Mr. Champoux. Again, I don't understand--when you use the word 'sectarian tenets to be taught in any public educational institution,' what do you do about a Department of Religious Studies? I agree with Mr. Brown. It seems to me that this is something to be studied and thought about and learned about."

- Delegate Champoux: "...if you go back to the original in the old [1889] Constitution, it says practically the same thing. As a matter of fact, in that area, it does say exactly the same thing. And the intent, of course, of the original section was to keep a public school teacher from teaching his particular religious tenets in the classroom. And this is the way it's been interpreted by the courts, as we understand it. Now, the University has, of course, had a School of Religion. I'm not quite sure, it isn't directly affiliated with the school-- the University, is it? Directly part of the University?"

- Delegate Bugbee: "Yes, it is."

- Delegate Champoux: "...Okay, now the only thing I can say at this point is that since the University has been able to do it up to this point without objection, I would say it's still allowed."

- Delegate Burkhardt: "...in speaking to the teaching of sectarian tenets, is a different concept than Mrs. Bugbee was referring to, where you have an attempt to understand in depth the meaning and the philosophy of various religious groups. That's one thing. Another thing is to advocate a particular tenet, and that is what this section originally was intended to protect, that you would not simply be, as in the University, examining in depth various philosophies and religions and thinking about them with some adult perspective."

Interaction with Bill of Rights: Discrimination

Wiki Author's Introduction: Like the Convention Commission foreshadowed a delegate might, Delegate Brown argued that Article 10, Section 7 constituted an unnecessary and confusing iteration of the rights expressed in the Bill of Rights under Article II, Section 4. Delegate Champoux responded that teachers who came before the Education Committee testified that political and religious hiring discrimination represents a discrete issue from those addressed in the Bill of Rights. Likewise, Delegate Cain pointed out that hiring in the educational setting is particularly vulnerable to the majoritarian political or religious views of a particular community. Delegate Robinson questioned whether entrance exams like the LSAT could be characterized as prohibited partisan testing. Delegate Champoux brushed her question aside, however, leaving the issue unanswered and potentially ripe for interpretation by the Montana Supreme Court. Ultimately, Delegate Brown's effort to delete Article X, Section 7 as redundant was unsuccessful.

- Delegate Brown: "Mr. Chairman. I'll move to delete Section 7. I'm not moving to delete this because I believe in discrimination in education. I want to make that clear. But Section 4 of our Bill of Rights fully covers any discrimination in the exercise of any of your civil and political rights and covers race, color, sex, cultures, social, political, religious ideas. And this is not in most Educational Articles in other constitutions. I feel it's surplus, because it's been covered."

- Delegate Champoux: "As Chairman of the committee, I feel I have to say something about this. I hadn't considered that, Mr. Brown, even though I was the mover of that particular one on discrimination in the Bill of Rights. We were concerned here about some problems in terms, well, first of all, of teachers that came up before the committee, teachers in certain areas. And, I believe, one of our committee members even made the point that he had experienced this where the community had been totally of one denomination-- regardless of what it had been-- and there'd been discrimination in that community in terms of hiring. That was one of the conditions. The other one was, if you'll notice, at the end, we've added the original statement said-- had something concerning just sex in terms of-- I mean-- discrimination in terms of higher eduction on the basis of sex. And we've extended it. Now, if you can satisfy us that this clause in the Bill of Rights does cover that, I would certainly be willing to accept it."

- Delegate Cain: "The consideration of the rights of teachers in placement without regard to religion and other external personal choices has come full-circle since I first began to teach. When I first began asking for teacher positions, there was a surplus of qualified teachers; there were more available than there were vacancies. A good opening was often obtained by political pull. Many application forms asked such questions as, 'What is your church affiliation? Do you attend weekly? Would you be willing to teach a Sunday School class? Do you play cards? Do you smoke? Do you drink? Do you support a political party?' Those days passed, and we came into a period where there were more vacancies than there were qualified-- and I emphasize qualified applicants. Now, we are again in a period like the late thirties, when teachers are unable to find jobs. Could it not happen again?"

- Delegate Robinson: "Mr. Champoux. On your-- this last section, dealing with discrimination, I noticed that in the Education proposed draft as compared with the Bill of Rights, you leave out political ideas, which was included in the Bill of Rights. And I-- was that intentional?"

- Delegate Champoux: "No ma'am, but we heard you had an amendment to put it in there. We haven't seen it yet, but we heard."

- Delegate Robinson: "Well, if Mr. Brown's move to delete does not prevail, I will offer such an amendment." [Delegate Robinson's amendment passed after she ultimately moved to amend.]

- Delegate Robinson: "The first section, as Mr. Davis indicated, has been interpreted to be religious or partisan test or qualifications. I'm not sure exactly what a partisan test is. But I think at a different time, and it may be a different court, could that not be interpreted to say that no test of any qualification could be required? That is, the University System would always be precluded from having entrance exams, for example?"

- Delegate Champoux: "In reference to your first question, a partisan test is usually interpreted as meaning belonging to one particular political party, for instance. These two last words, 'test' and 'qualification,' are nouns, as you well know, with the adjective modifier 'religious' and 'partisan.' Now, it has held up for the many years since the Constitution has been in force, where it has never been subjected to the test whether that means that there are no qualifications that apply. Where is that precedent, I would say that it has never been challenged, to my knowledge, on the basis of the argument you make. I think it would stand the test of time. In reference to Mr. Harlow's . . . Mr. Harlow brought up a good point, and Paul, I don't think at this point that our Constitution covers that, personally. And from the judges' opinions, apparently it doesn't, and I think it's certainly for a lack. If you look at-- there are two other things here, though, in reference to Mr. Brown's deletion movement, that are not applicable to the Bill of Rights section as I see it. For instance, it says here, 'nor shall attendance be required in any religious service whatever.' But more important than that, it says 'nor shall any sectarian tenets be taught in any public educational institution of the state.' Now, if we eliminate the entire section, we're going to be eliminating those two points too, and I think you should consider that.'

- Delegate Robinson: "It was not clear to me from your answer whether or not your committee dealt with the question of whether or not the institutions of higher learning in Montana could or could not use LSATs, or any kind of a test, for admission to the University."

- Delegate Champoux: "Well, Mrs. Robinson, I didn't grab that question to begin with, or understand it. The answer is 'No, we haven't; we didn't.' And I know of no case that's been-- come before the courts using this clause as a basis to support a test for entrance. It could perhaps; I don't know."

- Delegate Brown: "Mr. Chairman. I'll briefly close. I think the questions have showed that we just keep adding things; we get more confusion. And we do have religious studies in our institutions of higher learning-- I know Missoula does-- and discrimination is completely covered very broadly by the Bill of Rights. And I repeat, I see no reason to put more of this into the Constitution."

[On Delegate Foster's motion, Chairman Graybill initiated a roll call vote on Delegate Brown's motion to delete Section 7 in its entirety.]

- Chairman Graybill: "56 having voted No and 33 Aye, the motion fails."

Delegate Harbaugh's Attempt to Substitute Language

Wiki Author's Introduction: Delegate Harbaugh moved to revise the language of Section 7 to read as a guarantee more suited for the Bill of Rights. Delegates Champoux and Noble successfully led the resistance against this effort. For his part, Delegate Champoux seemed to imply that Delegate Harbaugh had raised this revision in the Education Committee; and, Delegate Champoux's implication extended to questioning whether Delegate Harbaugh simply wanted more religion inserted into public educational institutions. Additionally, Delegate Burkhardt, with Delegate Dahood's backing, emphasized that the proposed revision was so broad as to be unenforceable. The proposed revision was ultimately defeated.

- Delegate Harbaugh [as read into the record by Clerk Hanson]: "Substitute for Section 7. Mr. Chairman. 'All public educational institutions in this state shall guarantee the integrity of the diverse political, religious, cultural and social sectors of a pluralistic society. No discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, creed, or national origin shall be permitted in matters of employment in or admission to any public educational institution.'"

- Delegate Harbaugh [opening]: "...I move this substitute motion because we did discuss this in our Education Committee and, after quite a lot of discussion, decided to stay with the original section. Possibly, this would be a compromise-type of article. There was a time, certainly, in the history of our educational system where we needed a listing, perhaps, of the sort that is contained in the present section. However, I think that times have changed and that we have seen that strict statements, such as the one in the [1889 Constitution's] Article IX, have been construed sometimes in such a way that they prohibit some of the things that we maybe didn't want to prohibit; study of maybe certain religious material or this kind of thing in the public schools. And really, all I'm doing is trying to restate the tenets of the present section in a more positive language and term, so that it would not prohibit some of the things that I think we find desirable today in our educational institutions. Thank you."

- Delegate Noble: "As a member of the committee and the one who proposed this section, I resist Mr. Harbaugh's amendment. We talked in the committee, and the committee voted unanimously to adopt the other one."

- Delegate Champoux: "All right, now, when we talk about a pluralistic society, is it your intent, then, by this-- for the record perhaps to get more religion in our schools?"

- Delegate Harbaugh: "No. My intent is that . . . we simply not stifle the freedom of the student to study various beliefs and points of view. It's not my intention to make public school into an institution that instructs youngsters or promotes any particular religious point of view."

- Delegate Aasheim: "Mr. Chairman and delegates. I think we're concerned about this matter of 'taught,' and I think it's justified. I'm sure that we're not trying to hinder the teaching of religion in any University System; the comparative religions in the high schools or grade schools. What we are concerned about is promoting one particular religion over another..."

- Delegate Burkhardt: "I'm concerned, and I thought maybe as a lawyer, [Delegate Dahood], you could speak to this. As I read it, we are here guaranteeing the integrity of diverse sectors of a pluralistic society. It doesn't say we're defending them in school. We're on record to go out and promote them and defend them everywhere. I wonder how we're going to afford that and other questions."

- Delegate Dahood: "Yes, and I really have some doubt. In fact, I've expressed my opinion, and probably what we ought to do is find one sentence to indicate that we're not going to have any discrimination of any kind in education. And I think we'd be a lot better off."

- Delegate Wilson: "Yes, Mr. President. I think the old [1889 Constitution] section has served us well over the years. I don't see any quarrel with it at all. [The Committee] only added six words to the old section. I think this is sufficient and adequate. I think we know what we're voting on when we vote for it. I think the courts have determined that this is right, and I don't see any need to borrow trouble or stir up dissension. And I would urge the adoption of the majority [Committee] report."

[Chairman Graybill initiated a roll call vote on Delegate Harbaugh's motion to substitute for Section 7 the language: "All public educational institutions in this state shall guarantee the integrity of the diverse political, religious, cultural and social sectors of a pluralistic society. No discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, creed, or national origin shall be permitted in matters of employment in or admission to any public educational institution nor shall any sectarian tenets be advocated in any public educational institution of the state."]

- Chairman Graybill: "62 having voted No and 23 having voted Aye, the motion is defeated."

"Advocated" Replaces "Taught"

Wiki Author's Introduction: As discussed previously, the Delegates' concern about the blurred line between teaching religious principles and advocating for religious doctrines ultimately led them to substitute the word "advocated" for the original "taught."

- Clerk Smith [reading into the record Delegate Harper's motion]: "Mr. Chairman. I move to amend Education Article, page 5, Section 7, line 20, by changing the word 'taught' to the word 'advocated.'"

- Delegate Harper: "It's a one-word change, and I think it strikes at many of the comments that have been made here, so I won't belabor the point. I suppose most of us have had experience with this kind of conflict in the minds of people-- administrators and teachers in our public schools, as to just how far they can go in even bringing up religious subjects. Mr. Champoux said a moment ago that they didn't mind people studying them, but we didn't want them taught. Well, that's hard to do. It's pretty hard for any person to bring up a subject, in a sense, without teaching it, though it was possible when I was a student, I'm sure of that. The school person-- one schoolteacher, for example, invited me into a class on English Literature to talk about the Book of Job in the Bible. The next year, the same course was taught by another teacher, who felt that this would be a religious imposition on students, and so the format of the course was changed. It didn't make any particular difference to me. I simply use it as an illustration of the fact that the word "taught" does mean different things to different people. I think the word-- a word like "advocated," as Mr. Aasheim and I are suggesting, seems to be more directly to the point of what this whole section is about."

[Chairman Graybill called an oral vote on Delegate Harper's motion to replace "taught" with "advocated."]

- Chairman Graybill: "The Ayes have it, and it's amended."

Adoption

- Chairman Graybill: "Members of the body, you have before you for your consideration, on the recommendation of Mr. Noble that when this body does arise and report, after having had under consideration Section 7, as amended, we recommend it be adopted . . . the Ayes have it, and it's adopted."

Final Draft Floor Vote: March 17, 1972Mont. Const. Conv., Verbatim Transcript 2576.

Wiki Author's Introduction: Perhaps in an effort to distinguish Article X, Section 7 from the anti-discrimination guarantees found in the Bill of Rights, the drafters replaced "person" with "teacher or student." In this way, the Delegates mitigated textual redundancies and protected the interests of the teachers who testified in support of the provision.

- Delegate Schiltz: "Mr. Chairman, I move that when this committee does rise and report, after having had under consideration Section 7, Style and Drafting Report Number 10, it recommend the same be adopted. Mr. Chairman, there are no substantive changes. We did insert, instead of 'person' of line 28, 'teacher or student,' and I think we borrowed some of that from the comments. And I have gone over it with Mr. Champoux, and he had no problem there. We didn't know-- we couldn't see that any such tests would be applied to anybody other than teachers or students; and so that could be a basic change or a substantive change, but I don't think it is. That's all.

Report of Committee on Style, Drafting, Transition and Submission Final Report: Reported March 22, 1972Mont. Const. Conv., Comm. Report, Vol. II 1070.

Text

Section 7. NON-DISCRIMINATION IN EDUCATION. No religious or partisan test or qualification shall be required of any teacher or student as a condition of admission into any public educational institution. Attendance shall not be required at any religious service. No sectarian tenets shall be advocated in any public educational institution of the state. No person shall be refused admission to any public educational institution on account of sex, race, creed, religion, political beliefs, or national origin.

Ratification

1972 Official Text with Explanation:

Section 7. NON-DISCRIMINATION IN EDUCATION. No religious or partisan test or qualification shall be required of any teacher or student as a condition of admission into any public educational institution. Attendance shall not be required at any religious service. No sectarian tenets shall be advocated in any public educational institution of the state. No person shall be refused admission to any public educational institution on account of sex, race, creed, religion, political beliefs, or national origin.

- Proposed 1972 Constitution for the State of Montana: Official Text With ExplanationProposed 1972 Constitution of the State of Montana, "Voter Information Pamphlet" 15 (1972).

"Last sentence revises 1889 constitution which merely forbade denying any person entrance to a university because of his or her sex by broadening the language to include all public educational institutions and to include other kinds of discrimination. Other changes in grammar only."

- Gerald J. Neely, A Critical Look: Montana's New Constitution (1972)Gerald Neely, The New Montana Constitution: A Critical Look (1972) (available at https://www.umt.edu/law/library/montanaconstitution/campbell.php).

"Some of the major changes with respect to education in the new document are . . . broadened provisions prohibiting discrimination in admission to public educational institutions."

Interpretation

Commentary

- Linda J. Wharton, State Equal Rights Amendments Revisited: Evaluating Their Effectiveness in Advancing Protection Against Sex Discrimination (2005)<ref>Linda J. Wharton, State Equal Rights Amendments Revisited: Evaluating Their Effectiveness in Advancing Protection Against Sex Discrimination, 36 Rutgers L. J. 1201, n.2 (Summer 2005) (emphasis added).</ref>

"Two states—Wyoming and Utah—added sex equality guarantees to their constitutions at the same time that they extended the right of suffrage to women in the late nineteenth century. UTAH CONST., art. IV, § 1; WYO. CONST. art. I, § 2. California added a provision to its constitution that expressly prohibited sex discrimination in employment in 1879. CAL. CONST. art. I, § 8. Some states also explicitly provide protection against sex discrimination in public education in their constitutions. CAL. CONST. art. I, § 31(a); HAW. CONST. art. X, § 1; WYO. CONST. art. VII, §10; MONT. CONST. art. 10 § 7."