IX.1 Protection and Improvement

(1) The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations. (2) The legislature shall provide for the administration and enforcement of this duty. (3) The legislature shall provide adequate remedies for the protection of the environmental life support system from degradation and provide adequate remedies to prevent unreasonable depletion and degradation of natural resources. Mont. Const. art. IX., § 1.

History

Sources

Drafting

Committee Proposal

On March 1, 1972, the Natural Resources and Agricultural Committee originally proposed Article IX, § 1(1) as: “Section 1, Protection and Enhancement. The State of Montana and each person must maintain and enhance the environment of the state for present and future generations.” This did not include the current obligation to “maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment.” “Subsection 2. The Legislature must provide for the administration and enforcement of this duty. Subsection 3. The Legislature is directed to provide adequate remedies for the protection of the environmental life support system from degradation and to provide adequate remedies to prevent unreasonable depletion and degradation of natural resources.” Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. 4 at 1200, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol4.pdf.

Delegate Proposals

Delegate James initially proposed an amendment to the language of the originally proposed Article IX, § 1(1) “to remove ‘the’ and insert “a clean and healthful”; delete “of the state” and insert “for the protection and enjoyment of present and future generations.” After a roll call vote of 40 delegates voting aye, and 44 voting no with 16 absent, Delegate James’s proposal was lost. Id. at 1202-1210.

Several other delegates proposed separate amendments which included variations of “a clean and healthful” until the descriptive adjectives of Art. IX, § 1(1) proposed by Delegate Campbell were ultimately accepted. Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. 5 at 1229-1251, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

Delegate Cross made a proposal to strike language in both subsection 2 and 3 to include: “To meet the obligation set forth in Section 1, each Montana resident may take appropriate legal proceedings against any party, governmental or private, subject to reasonable limitation and regulation as the Legislative Assembly may provide by law.” The proposal was defeated with 44 delegates voting aye, and 46 voting no with 10 delegates either absent or excused. Id. at 1251-1254.

Floor Debate

On the proposed “clean and healthful” amendment:

As originally proposed, Committee members believed the provision was the strongest environmental protection of any state constitution without the proposed amendment including “clean and healthful.”

Delegate McNeil: “Your committee presents and recommends, in its proposal, the strongest constitutional environmental section of any existing state constitution. Subsection 1 requires the state and each person, which, of course, includes corporations and all legal entities as well as individuals, to maintain and enhance the Montana environment for present and future generations. . . In addition, the provision drafted by the majority requires that we, at least at a minimum, maintain the present Montana environment. Your committee considered, at length, an exhaustive list of descriptive adjectives to precede the word environment, such as healthful, pleasing, quality, high-quality, unsoiled, and, finally, my very own, unique, and concluded that no descriptive adjective was adequate or necessary. This was not considered by the majority to be a compromise, but rather an acknowledgement of the present Montana environment as encompassing all of those descriptive adjectives. Constitutional provisions of other states were studied, but none were considered adequate, as no other state has Montana’s environment. And therefore, your committee felt that the best recommendation is to require that all must maintain and enhance the Montana environment. . . The majority felt that the use of the word ‘healthful’ would permit those who would pollute our environment to parade in some doctors who could say that if a person can walk around with 4 pound of arsenic in his lungs or SO_2 gas in his lungs and wasn’t dead, that that would be a healthful environment. We strongly believe – the majority does – that our provision – or proposal is stronger than using the word ‘healthful.’” Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. 4 at 1200-1201, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol4.pdf.

After Delegate James proposed the “clean and healthful” amendment to be included in subsection 1, a number of Delegates expressed their views on including the descriptive adjectives:

Delegate Campbell believed that without “clean and healthful” the section lacked the force it was intended to have. “I feel that the present section, as presented by the committee, stating that the State of Montana will maintain an environment is absolutely worthless. What this says, in effect, instead of being the strongest in the nation, is that there is no type of standard whatsoever to define this environment. A ‘clean and healthful environment’ is not defined. It would be defined by the Montana Supreme Court and the Legislature that we are hoping will initiate effective controls. All of this says that they will enhance the environment. It does not describe whether it is good environment, bad environment, polluted environment, or anything.” Id. at 1204, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol4.pdf.

Delegate John Anderson on the originally proposed subsection: “I feel that subsection 1 of Section 1 spells it out very clearly that we must maintain this quality environment that we have-and not only maintain it, but improving it; as the article says, to enhance it.” Id.

Delegate McNeil added: “[T]he majority felt this would permit degradation of the present Montana environment to a level as defined in Illinois, which may be clean and healthful. And our intention was to permit no degradation from the present environment and affirmatively require enhancement of what we have now.” Id. at 1205.

To address concerns about interpretation of Art. IX, § 1 by the courts and the implications of including descriptive adjectives, Delegate Heliker consulted University of Montana Law Professor John McCrory, who stated, “Contrary to the view of the committee majority, I believe that descriptive adjectives are necessary for guidance for interpreting the Constitution, to insure that present problems are not perpetuated. The words ‘clean and healthful’ have common usage and meaning which would furnish such guidance.” Id. at 1206.

It was the intent of many delegates to vote for what they believed included the strongest protecting language. Delegate McNeil stated: “I want the record to clearly reflect that I am not voting against Mr. James’ amendment, but rather voting for what I believe to be the stronger statement. And I believe the entire delegation will agree that, whichever we adopt, that it is the intention of this Convention to adopt the stronger of the two.” Id. at 1209.

On the interrelationship of subsections 1 and 3:

Delegate McNeil stated: “Subsection 3 mandates the Legislature to provide adequate remedies to protect the environmental life-support system from degradation. The committee intentionally avoided definitions, to preclude being restrictive. And the term “environmental life support system” is all-encompassing, including but not limited to air, water, and land; and whatever interpretation is afforded this phrase by the Legislature and courts, there is no question that it cannot be degraded. . . Subsection 3 further mandates the Legislature to provide adequate remedies to prevent unreasonable depletion and degradation of natural resources. Although it is recognized that some nonrenewable natural resources are to be consumed, this provision permits the Legislature to determine whether the resources [are] being unreasonably depleted and requires preventive remedies.” Id. at 1201.

Delegate Robinson further contended: . . . “that if you're really trying to protect the environment, you'd better have something whereby you can sue or seek injunctive relief before the environmental damage has been done; it does very little good to pay someone monetary damages because the air has been polluted or because the stream has been polluted if you can't change the condition of the environment once it has been destroyed.” Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. 5 at 1230, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

Delegate Gysler defended the originally-proposed subsection 3, stating: “The reason that the majority did not support a separate section saying “the right to sue”, the paragraph 3 of our report states, “The Legislature is directed to provide adequate remedies for the protection of the environmental life support system from degradation and to provide adequate remedies to prevent unreasonable depletion of natural resources.” Now, to those of us that studied what we were doing for a long time before we did it, we felt that this, in itself, is a lot stronger than, certainly, the proposal we're looking at right now.” Id. at 1232-1233.

Adoption

After a roll call vote of 49 delegates voting aye, and 38 voting no with 13 either absent or excused, Delegate Campbell’s proposal was passed by the Convention on March 1, 1972. Id. at 1246-1251.

After a voice vote, Chairman Graybill announced subsections 2 and 3 were adopted by the Convention on March 1, 1972. Id. at 1254-1255.

Inalienable Rights

Delegate Burkhardt proposed the right to a clean and healthful environment be added to the inalienable rights found in Art. II, § 3. After a roll call vote of 79 delegates voting aye, and 7 voting no with 14 either excused or absent, Delegate Burkhart’s proposed amendment was adopted and included as an inalienable right on March 7, 1972. Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. 5 at 1637, available at https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

In making this proposal, Delegate Burkhardt stated: “This is a statement that we, as a body, have already adopted in another section of our Constitution, in our Natural Resources section. We have the statement: “It shall be the duty of the State of Montana and each person to maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment.” And it seems to me that it’s simply striking the other side of the balance to put it here in our Bill of Rights, to recognize that this is, for the time in which we’re living and for the foreseeable future, one of the inalienable rights that we hope to assure for our posterity.” Id.

Ratification

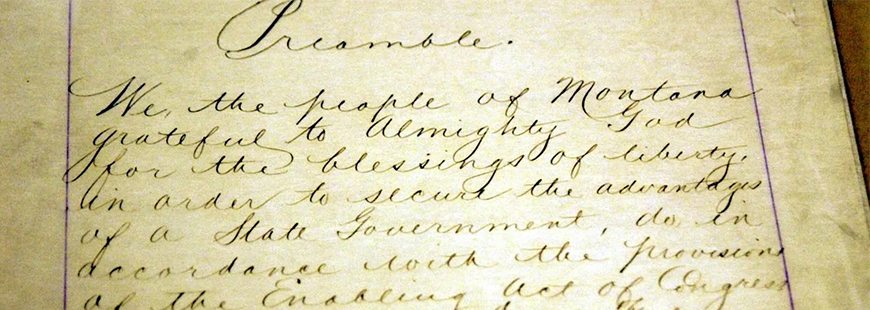

1972 Official Text with Explanation

“New provision creating a duty of the state and its people to protect and improve the environment. D.O.W.R & C.”Official Proposed Constitution Voter Information Pamphlet. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library/MontanaConstitution/Miscellaneous%20Documents/Const%20VIP.pdf

Gerald Neely’s Commentary

Gerald Neely was a Billings attorney during the Constitutional Convention, and edited the statewide publication called the “Con Con Newsletter.” This newsletter was hailed as “....one of the best publications we have ever seen” by the Citizens Conference on State Legislatures. Mr. Neely also served as a United Press International wire reporter.

“The state, each person, and all legal entities must—under the new document—"maintain and enhance" Montana's environment with the legislature to administer and enforce this "duty." (Art. IX, sec. 1(1),(2)). Rejected by the Convention was the controversial "public trust” doctrine whereby the state would hold in trust all land for the benefit of the people. Under the proposal, the legislature must provide "adequate remedies" to protect the environment—air, water, land, natural resources—from degradation and "unreasonable" depletion. (Art IX, sec. 1(3)). The provision permits the legislature to determine whether the resource is being unreasonably depleted and requires preventive remedies. If that includes class actions by individuals without the necessity of showing direct damage to the individuals, the legislature would have to so provide. The proposal is the strongest environmental section of any existing state constitution. See section 3, Bill of Rights.” Neely, Gerald J., The New Montana Constitution: A Critical Look. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library%5CMontanaConstitution%5CCampbell/NeelyPamphlet.pdf

Montana Chamber of Commerce Newsletter

The Montana Chamber of Commerce developed a policy statement about the proposed 1972 Constitution in which they offered general commentary about each article of the new Constitution ahead of the special ratification session. Their general opinion of the proposed Constitution was that “[b]ecause the provisions of the proposed Constitution are so broad in their scope and impact with the pros and cons so evenly balanced, the Board of Directors urge all members to study carefully and give thoughtful consideration to all provisions of the proposed Constitution and then vote June 6th in such a manner as to reflect their own best interest and the long-range good of Montana."

More specifically, the Chamber offered the following commentary on article IX: “While business is rightly concerned about provisions contained in this article and their possible application by ecology extremists, careful reading fails to show that any new powers or actions are extended or mandated beyond the types of ecology/environmental statutes already enacted. It was generally felt that Section 3, Water Rights, is an improvement over existing provisions. It was noted that Section 3 is necessary if Montana is to be able to protect our water against downstream appropriation or inter-regional diversion!”Montana Chamber of Commerce Newsletter. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library/MontanaConstitution/MHS%20Ratif/Cham%20Comm%20Newsletter%20ocr.pdf

Farm Bureau Pamphlet

The Farm Bureau released a pamphlet ahead of the special ratification session, which included commentary from a number of concerned citizens. The pamphlet begins with some general commentary from the Farm Bureau president Bernard Harkness in which he expressed his inability to support the proposed commentary. In the “Critical Comments” section of the pamphlet, he made the following comments on article IX, section 1:

“The above sub-sections on environment directs the state legislature to provide for class action . . . . The effects of such legislation would allow an individual to bring action against an industry or another individual even though he may not be directly affected. ‘Future generations’ creates an ambiguity. Should it be for the 10th or 20th generation?”1972 Farm Bureau Pamphlet. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library/MontanaConstitution/MHS%20Ratif/Farm%20Bureau/Farm%20Bureau%20Pamphlet.pdf

Billings Gazette, April 1-12, 1972

In an article by Charles S. Johnson, entitled “Delegates dispute environmental rule,” Mr. Johnson reports that the provisions in the proposed Constitution were the strongest environmental protections in any state constitution, but that some, like Louise Cross, D-Glendive, fought for provisions with “more teeth.” Another delegate deeply involved in the environmental provisions of the Constitution, C.B. McNeil, R-Polson, noted that “[The environmental section] is especially important when you consider that most delegates came here with the idea of streamlining the old constitution, but they believed the environment so important they added a new provision.”Johnson, Charles, "Delegates dispute environmental rule," Billings Gazette, April 1-12, 1972. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library/MontanaConstitution/MT%20Newspapers%20Mansfield/Billings%20Gazette%200401-1272%20ocr.pdf

Delegate Lucile Speer's Letter

Lucile Speer, D-Missoula, wrote a letter to Dr. Richard Roeder in April of 1972 reporting “some penetrating questions from the ‘politically alert’ people in Missoula." On the environmental provisions, she had the following to share from her constituents:

“Naturally, the environmentalists (including most of campus) are disappointed. On the other hand, two senior citizens wanted to know if the provisions on natural resources would prevent them from cutting trees on their ranches or would take away their 'rights' to streams starting on their land!”

She went on to discuss her conversations with labor interests, who were not terribly upset by the environmental article. In her estimation, this was likely evidence of “how innocuous it is.”

This information was presented to Dr. Roeder in the context of Speer’s general dismay at how little most people she spoke with knew about the proposed Constitution.Speer, Lucile letter to Dr. Richard Roeder, April 21, 1972. http://www.umt.edu/media/law/library/MontanaConstitution/Roeder%20Collection%20at%20MSU/FAQ%20-%20Roeder%20tabloid%20prep.pdf

Interpretation

Cases

1999: Montana Envtl. Info. Ctr. (MEIC) v. Dep’t. of Envtl. Quality

In MEIC, the Court reasoned that “to give effect to the rights guaranteed by Art. II, § 3 and Art. IX, § 1 of the Montana Constitution they must be read together and consideration given to all of the provisions of Art. IX, § 1 as well as the preamble to the Montana Constitution. In doing so, we conclude that the delegates' intention was to provide language and protections which are both anticipatory and preventative. The delegates did not intend to merely prohibit that degree of environmental degradation which can be conclusively linked to ill health or physical endangerment. Our constitution does not require that dead fish float on the surface of our state's rivers and streams before its farsighted environmental protections can be invoked. The delegates repeatedly emphasized that the rights provided for in subparagraph (1) of Art. IX, § 1 was linked to the legislature's obligation in subparagraph (3) to provide adequate remedies for degradation of the environmental life support system and to prevent unreasonable degradation of natural resources.” Montana Evtl. Info. Ctr. v. Dep’t of Envtl. Quality, 1999 MT 248, ¶ 77, 296 Mont. 207, 988 P.2d 1236.

The Court noted the intent of the Constitution framers for the rights guaranteed in Art. II, § 3 and the rights within Art. IX, § 1 to be interrelated and interdependent. The Court therefore concluded that the implication of those rights in either Art. II, § 3 or Art. IX, § 1 required strict scrutiny (to be narrowly tailored to a compelling state interest.) Id. at ¶¶ 63-65.

2001: Cape-France Enters. v. Estate of Lola H. Peed

In Cape-France Enterprises, the Court applied the protections and provisions of Art. IX, § 1 to private action and private parties. Cape-France Enters. v. Estate of Lola H. Peed, 2001 MT 139, ¶ 32, 305 Mont. 513, 29 P.3d 1011. “Causing a party to go forward with the performance of a contract where there is a very real possibility of substantial environmental degradation and resultant financial liability for cleanup is not in the public interest; is not in the interests of the contracting parties; and is, most importantly, not in accord with the guarantees and mandates of Montana’s Constitution, Art. II, § 3 and Art. IX, § I.” Id. at ¶ 37.

2012: Northern Plains Resource Council, Inc. v. Montana Board of Land Comm'rs

In Northern Plains Resource Council, the Court reasoned that “because the leases themselves do not allow for any degradation of the environment, conferring only the exclusive right to apply for State permits, and because they specifically require full environmental review and full compliance with applicable State environmental laws, the act of issuing the leases did not impact or implicate the right to a clean and healthful environment in Article II, Section 3 of the Montana Constitution.” Northern Plains Resource Council, Inc. v. Montana Board of Land Comm'rs, 2012 MT 234, ¶ 19, 366 Mont. 399, 288 P.3d 169. Since unlike MEIC, the leases did not implicate fundamental rights to a clean and healthful environment, strict scrutiny was not required. Id. at ¶ 20.

2020: Park County Envtl. Council (PCEC) v. Montana Dep’t. of Envtl. Quality

In PCEC, the Court was faced with determining whether a statutory amendment barring equitable remedies for violations of the Montana Environmental Policy Act was unconstitutional under Art. II, § 3 and Art. IX, § 1. Park County Envtl. Council v. Montana Dep’t. of Envtl. Quality, 2020 MT 303, ¶¶ 52. The amendment at issue allowed for projects to operate even when they were approved for operation without the proper environmental review by MEPA. Id. at ¶ 57. The only remedy allowed under the statute was to remand to the DEQ to complete its review, however, the project could not be forced to stop during the course of that review. Id. The Court reasoned: “As in MEIC, the 2011 Amendments at issue here are unconstitutional because they undercut the State’s ability to determine in advance whether a given activity will cause environmental harm and thereby take actions to “prevent unreasonable depletion and degradation of natural resources” as required by Art. IX, § 1(3), of the Montana Constitution. Additionally, the 2011 Amendments categorically remove the Plaintiffs’ only available remedy adequate to prevent potential constitutionally-proscribed environmental harms, in violation of Art. IX, § 1(3), of the Montana Constitution’s guarantee of ‘adequate remedies.’” Id. at ¶ 88. The court concluded the amendment was not narrowly tailored to further a compelling state interest. Id. at ¶ 86.

The PCEC Court determined that its conclusion of the amendment being unconstitutional “flows from the content of the statute itself, not the particular circumstances of the litigants,” making the amendment facially unconstitutional. Id. at ¶ 86. In MEIC, however, the Court limited its decision to be applied to the facts of the case rather than analyze it as a facial constitutional challenge even though both the MEIC and PCEC Courts were faced with similar blanket exceptions. Id. at ¶ 87. Justice Leaphart offered a special concurrence in MEIC which was adopted by the PCEC Court stating:

“I do not see how the Court can logically avoid declaring that the statute is unconstitutional on its face. The constitutional infirmity of § 75-5-317(2)(j), MCA (1995), is not limited to the facts in the present case but inheres in the statute’s creation of a blanket exception. It creates a blanket exception to the requirements of nondegradation review for discharges from water well or monitoring well tests without regard to the harm caused by those tests or the degrading effect that the discharges have on the surrounding or recipient environment. The fact that there may be water discharges from well tests, say for agricultural purposes, that do not in fact create harm to the environment, does not alter the fact that such discharges are exempted from nondegradation review and that such review is the tool by which the State implements and enforces the constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment. The facial unconstitutionality of § 75-5-317(2)(j), MCA (1995), lies in its exemption of particular water discharges from nondegradation review without consideration of the nature and volume of substances in the water that is discharged. The possibility that some water discharges will not harm the environment does not justify their exemption from careful review by the State to protect Montana’s fundamental rights to a clean and healthy environment and to be free from unreasonable degradation of that environment. The whole purpose of the nondegradation review is to determine, in advance, whether a water discharge will be harmful and, if so, is the harm justified and can it be minimized. See § 75-5-303, MCA. In excluding water discharges from well tests from review, the statute makes it impossible for the State to “prevent unreasonable depletion and degradation of natural resources” as required by Art. IX, § 1(3), of the Montana Constitution.” Id.

Legislation

Montana Environmental Policy Act (Mont. Code Ann. Title 75)

Public Trust Doctrine (Mont. Code Ann. § 77-1-102)

Commentary

Cameron Carter, Kyle Karinen, A Question of Intent: the Montana Constitution, Environmental Rights, and the MEIC Decision, 22 Pub. Land & Resources L. Rev. 97 (2001).

Jack Tuolske, The Legislature Shall Make No Law . . . Abridging Montanan’s Constitutional Right to a Clean and Healthful Environment, 15 Se. Envtl. L.J. 311 (2007).

Gregory S. Munro, The Public Trust Doctrine and the Montana Constitution as Legal Bases for Climate Change Litigation in Montana, 73 Mont. L. Rev. 123 (2012).

Hallee C. Kansman, Constitutional Teeth: Sharpening Montana’s Clean and Healthful Environment Provision, 81 Mont. L. Rev. 247 (2020).