II.19. Habeas Corpus

The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall never be suspended.

History

Sources

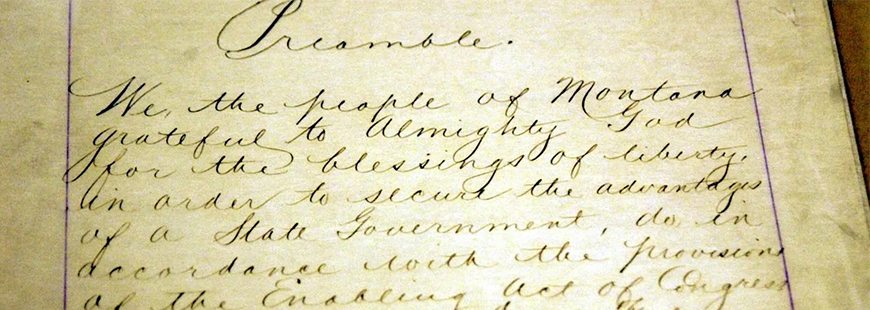

1884 Montana Constitution (proposed)

That the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall never be suspended, unless in case of rebellion or invasion the public safety require it. Mont. Const. art. I, § 21.

1889 Montana Constitution

The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall never be suspended, unless, in case of rebellion, or invasion, the public safety require it. Mont. Const. art. III, § 21.

Other Sources

Drafting

Bill of Rights Committee Proposal (Comments)

The committee believes that this most basic of procedural rights requires complete protection. Accordingly, the proposal provides that the writ of habeas corpus--the right to test the legitimacy of one's detention--ought never to be suspended. The committee is aware that a serious rebellion or invasion could lead to a federal suspension of the writ. However, it is urged that the state of Montana should not suspend the writ at the state level without a problem of such magnitude as to require federal action. It seems plain that the federal government could be counted upon to assist in keeping the state courts open to review any habeas corpus petitions submitted even in a statewide emergency.

The committee notes that nine states have similar provisions that guarantee that the writ shall never be suspended. The importance of the writ can be seen in Montana history. In 1914, when the Governor proclaimed a state of insurrection in Silver Bow county, the military closed down the courts in that county and arrested persons without warrant or charge, held them without bail to be tried without a jury before a military tribunal. Some of those detained used the writ of habeas corpus to good effect, securing an order that the military re-open the courts in Silver Bow County. (In re McDonald, 49 Montana 454, 143 P. 947 (1914)). The committee cites this as an example of the value of this important procedural safeguard precisely in times of stress.Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. II, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal 638-639.

Montana Constitutional Convention Floor Debate

Delegate R.S. Hanson: The present language is shown in our Bill of Rights: "The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall never be suspended." In the present section, Number 21, we have deleted the words "unless in case of rebellion or invasion, the public safety requires it." The committee felt that we would be accomplishing what we wante dto by cutting out the last words. We hope that you will move for the amendment--or the adoption of this section.

After a brief comment from Delegate Johnson regarding the "cowboys down in Powder River country" and their love of the words "habeas corpus," Section 19 was unanimously adopted.5 Verbatim Transcript 1764 (Mar. 8, 1972).

Ratification

1972 Official Text with Explanation: Revises 1889 constitution which allowed the writ of habeas corpus to be suspended in case of rebellion or invasion. Revision provides that the writ (the right to test the lawfulness of a person's being detained) may never be suspended.

Interpretation

Mont. Code Ann. § 46-22-101 (1981)

Mont. Code Ann. § 46-22-101 (1985)

Mont. Code Ann. § 46-22-101 (currently in force)

Lott v. State (2006)

In light of the writ's history and purpose, as well as Montana's constitutional guarantee in Article II, Section 19, that the writ of habeas corpus shall never be suspended, we conclude that, as applied to a facially invalid sentence--a sentence which, as a matter of law, the court had no authority to impose--the procedural bar created by § 46-22-101(2 ), MCA, unconstitutionally suspends the writ.Lott v. State, 150 P.3d 337, 342 (Mont. 2006).

When the delegates ratified the 1972 Constitution, they intended, at a minimum, that an individual incarcerated pursuant to a facially invalid sentence--for example, a sentence which either exceeds the statutory maximum for the crime charged or which violates the constitutional right to be free from double jeopardy--have the ability to challenge its legality.Id.

Beach v. State (2015)

In Lott v. State, 2006 MT 279, 334 Mont. 270, 150 P.3d 337, we held that statutory limitations on the availability of the writ of habeas corpus are unconstitutional under Article II, Section 19 of the Montana Constitution as applied to an offender sentenced to a “facially invalid sentence” where the facial invalidity stems from a rule created after time limits for directly appealing or petitioning for postconviction relief have expired. Lott, ¶ 22.Beach v. State, 2015 MT 118 at 6.

Rather than a mere deterrent, the writ is the “birthright of the people” and “one of the most important safeguards of the liberty of the subject.” Lott, ¶ 6. Indeed, our Constitution guards the writ more completely than the Federal Constitution. Compare Mont. Const. art. II, § 19 with U.S. Const. art. I, § 9. Rather than primarily a deterrent to the courts, the writ in Montana is a tool for achieving justice.Id. at 61 (Wheat, J., dissenting).

Montana’s habeas statutes—which I contend should be applied in this case—compel a different result. Our own habeas corpus statutes indicate different restrictions than those created by the federal framework.Id. at 90 (Shea, J., dissenting).

[T]he seemingly broad right granted by § 46-22-101(1), MCA, is appropriately constrained by § 46-22-102, MCA, which places a restriction on what sorts of claims may be raised in a habeas proceeding, and which may be subject to the retroactive application of new constitutional rules on habeas review. This statute provides: “A person may not be released on a writ of habeas corpus due to any technical defect in commitment not affecting the person’s substantial rights.” Section 46-22-102, MCA. Unlike § 46-22-101(2), MCA, which we held unconstitutional in Lott v. State, 2006 MT 279, 334 Mont. 270, 150 P.3d 337, § 46-22-102, MCA, comports with both the protection of the writ enshrined in the Montana Constitution and the historical purposes of habeas corpus.Id. at 105 (Shea, J., dissenting).