II.28. Criminal Justice Policy — Rights of the Convicted

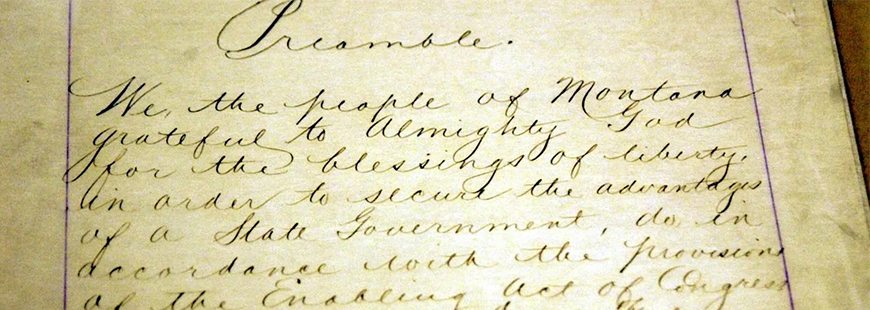

Montana Constitution of 1972

(1) Laws for the punishment of crime shall be founded on the principles of prevention, reformation, public safety, and restitution for victims. (2) Full rights are restored by termination of state supervision for any offense against the state.Mont. Const. art. II., § 28.

Drafting

(1) Laws for the punishment of crime shall be founded on the principles of prevention, reformation, public safety, and restitution for victims

The 1972 Constitutional Convention Bill of Rights Committee proposed the 1889 language of the first clause to remain the same. "Montana Constitutional Convention, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. 34, Vol. I, 128 In both the 1889 and 1972 Constitutions, the laws for punishment of crimes in Montana were founded solely on prevention and reformation. Id. The provision remained unchanged until the 1997 legislative session.

Representative Rod Bitney, a Republican from Kalispell, proposed HB 234, which placed a legislatively referred constitutional amendment on the 1998 ballot. 1997 Montana Legislature Senate Judiciary Committee notes. HB 234 was unopposed in hearings and succeeded in placing C-33 on the 1998 ballots. Id. C-33 proposed two principles to add to the clause: public safety and restitution for victims. Legislatively Referred Constitutional Amendment C-33 (1998) Voter Information Pamphlet Proponents of the amendment argued that although the rights of criminals are protected by the Montana Constitution, it "does not even mention the victims of crimes." Id. The argument for the amendment claimed that "no less tha[n] 10 percent of our state's population is a current victim" and that "[t]he approval of this Constitutional amendment would be one step in reforming a criminal justice system which far too often focuses only on the rights of the criminal." Id.

Mae Nan Ellingson (formerly Robinson), an original delegate of the 1972 Constitutional Convention, helped author the opponents' rebuttal of the issue. Id. Opponents to the amendment cited numerous laws that already protect the rights of the victim or provide for restitution, such as MCA 46-18-101 (requiring judges to emphasize restitution in sentencing); MCA 46-18-201 (requiring restitution to victims who suffer financial loss); MCA 46-18-115 (victims rights to make statements during sentencing hearings and offering opinions regarding appropriate sentences); and MCA 45-5-512 (allowing the court to restrict a defendant's employment and freedom of association to protect the victim, as well as allowing for the forced treatment of sex offenders with drugs to reduce likelihood of future offenses). The opponents also highlighted the Crime Victims Compensation Act of Montana, codified at MCA 53-9-1.

C-33 was approved by a wide margin in the 1998 election, passing with 71.38% of the votes, permanently adding the principles of public safety and restitution for victims to Art. II § 28 of the Montana Constitution. Montana Secretary of State, Historical Constitutional Initiatives and Constitutional Amendments, Accessed May 2016 (http://sos.mt.gov/Elections/forms/history/constitutionalmeasureslist2012.pdf)

(2) Full rights are restored by termination of state supervision for any offense against the state

The 1972 provision has one major change from its 1882 counterpart. Delegate Bob Campbell and the Bill of Rights commission elected to remove the 1882 provision that disenfranchised convicted felons for life. Montana Constitutional Convention, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. 34, Vol. I, 128 The committee considered the burdensome pardons system that a felon would have to navigate in order to vote and believed that "such a permanent punishment is contrary to the best interests of society, in that it does nothing to aid rehabilitation of a criminal." Montana Constitutional Convention, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. 34, Vol. I, 337 The removal of the 1882 provision was passed by a unanimous vote. Montana Constitutional Convention, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. 34, Vol. II, 643

The provision overlaps with sections two and four of Article IV of the Montana Constitution. Section two provides that a person is a qualified elector "unless he is serving a sentence for a felony in a penal institution" Mont. Const. Art. IV § 2 whereas section four states that people can run for public office once there is a "final discharge from state supervision." Mont. Const. Art. IV § 4 There was considerable debate as to whether full rights should be restored upon release from a penal institution, as provided in Art. IV § 2, or until final discharge from state supervision, as in Art. IV § 4. The delegates debated as to whether to amend the provision to delay the restoration of rights until complete termination of all state supervision, including parole. Most delegates were concerned that a recently paroled felon would be able to immediately be elected to public office, which they claimed would not be in the best interest of society. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 529 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Ultimately, the delegates approved the amendment by a vote of 86-6, delaying the restoration of rights until "termination of state supervision." Id.

Delegate Habedank proposed the following amendment to the provision: “Nothing contained in this section shall . . . allow a person convicted of crime to continue in or enter any business, trade, occupation or profession when prohibited from engaging therein by the licensing provisions provided by law.” Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1882 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Delegate Habedank was concerned that professional licensing boards were reinstating licenses simply because convicted individuals were being released from prison. Id. Delegate Campbell responded that the proposed amendment would eliminate any discretion on behalf of the licensing boards and that their decisions should be based on the individual merits of the applicant, not their criminal history. Id. The proposed amendment failed by a vote of 54-24. Id.

Proposed: Death shall not be prescribed as a penalty for any crime

The most widely contest provision of the Bill of Rights committee's proposal considered abolishing the death penalty. The 1889 Constitution initially had a provision stating that the principles of reformation and prevention "shall not effect the power of the legislative assembly to provide for punishing offenses by death." Montana Constitutional Convention, Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. 34, Vol. I, 128 The committee elected to remove the provision because it effectively granted the legislature a power it already had. Id. In its place, Delegate Campbell wanted a provision that stated that "[d]eath shall not be prescribed as a penalty for any crime." Id.

The committee realized the polarizing nature of abolishing the death penalty and were concerned that the Constitution could be rejected by voters simply because of their opposition to abolition. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1802 (Mont. Legis. 1972). The committee proposed that the incorporation of the abolition provision be put in front of voters alongside the Constitution for ratification as a stand-alone provision. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1803 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Regardless, Delegate Arbanas proposed that the convention incorporate the abolition of the death penalty directly into Art. II § 28. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1800 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Delegate Arbanas argued that the nation, as a whole, was moving away from capital punishment. Id. It should be noted that the convention was held after the United States Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Furman v. Georgia, but before they had issued a ruling (Furman v. Georgia implemented a nation-wide moratorium on the death penalty, finding its application to be arbitrary and in violation of the 8th Amendment of the United States Constitution). Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) Delegate Arbanas believed that it would soon be abolished nationwide and he wanted to "see Montana take a lead on something." Id. A long debate ensued demonstrating considerable division among the delegates.

After a lengthy debate between numerous delegates, Delegate Arbanas's proposal to incorporate the provision in Section 28 failed by a vote of 48-42. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1815 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Following the vote, Delegate Campbell again pushed for the abolition clause to be put on a separate ballot during ratification. Delegate Kelleher quickly proposed an amendment to the abolition clause that would carve out exceptions that allow use the death penalty for people convicted of killing law enforcement officers, prison guards, or if the defendant was convicted of a second capital felony. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1815 (Mont. Legis. 1972). The proposal was summarily dismissed by oral vote after delegate Campbell pointed out that the amendment "would not allow the legislature to have the complete flexibility that it should have." Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1817 (Mont. Legis. 1972).

The delegates continued to debate the provision to the point that Delegate Scanlin joked that "we've beat the death penalty to death." Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1818 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Delegate Campbell pushed the convention for a vote, but first read a letter from an inmate in Montana he had recently received. The letter detailed a prisoner whose cell mate confided in him that he had framed an innocent man for a crime he committed. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1820 (Mont. Legis. 1972). The letter emphatically demonstrated that innocent people do get convicted, largely proving Delegate Campbell's point moments before roll. The delegates approved the committee's proposal to create a separate ballot for abolition by a vote of 58-35. Mont. Const. Convention, Comm. Reps. and Transcrs., 1821 (Mont. Legis. 1972). Despite many delegates best efforts to constitutionally abolish the death penalty, the voters retained it by a vote ratio of three to one. Larry M. Elison and Fritz Snyder, The Montana State Constitution: A Reference Guide, p. 15 (2001)