II.3 Inalienable Rights

Montana Constitution of 1972:

"'All persons are born free and have certain inalienable rights. They include the right to a clean and healthful environment and the rights of pursuing life’s basic necessities, enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and seeking their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways. In enjoying these rights, all persons recognize corresponding responsibilities.Mont. Const. art. II., § 3.&l

History

Pre-Revolutionary War “inalienable rights” passages

Concessions and Agreements of West New Jersey, dated March 13, 1677:

That no Proprietor, freeholder or inhabitant of the said Province of West New Jersey, shall be deprived or condemned of life, limb, liberty, estate, property or any ways hurt in his or their privileges, freedoms or franchises . . .Concessions and Agreements of West New Jersey Chapter XVII. Reprinted in Neil H. Cogan, Contexts of the Constitution: A Documentary Collection on Principles of American Constitutional Law 677 (Foundation Press 1999) (hereinafter Cogan).

John Locke, The Second Treatise, an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government (1698):

Man being born . . . with a Title to perfect Freedom, and an uncontrouled enjoyment of all the Rights and Priviledges of the Law of Nature, equally with any other Man, or Number of Men in the World, hath by Nature a Power, not only to preserve his Property, that is, his Life, Liberty and Estate, against the Injuries and Attempts of other Men . . .John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, The Second Treatise, an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government, Chapter VII, ¶ 87. Reprinted in Cogan, supra n. 2, at 125.

"Inalienable rights” during the Revolutionary War Era

Declaration and Resolves [of the First Continental Congress], dated October 14, 1774:

That the inhabitants of the English colonies in North-America, by the immutable laws of nature . . . have the following RIGHTS: . . . That they are entitled to life, liberty and property[.] Declaration and Resolves [of the First Continental Congress]. Reprinted in Cogan, supra n. 2, at 27.

Virginia Declaration of Rights, dated June 7, 1776:

That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Declaration of Independence (1776):

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness[.]

Jeremy Bentham, Short Review of the Declaration (1776):

“All men,” they tell us, “are created equal.” This surely is a new discovery; now, for the first time, we learn, that a child, at the moment of his birth, has the same quantity of natural power as the parent, the same quantity of political power as the magistrate.

The rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”—by which, if they mean any thing, they must mean the right to enjoy life, to enjoy liberty, and to pursue happiness—they “hold to be unalienable.” This they “hold to be among truths self-evident.” At the same time, to secure those rights, they are content that Governments should be instituted. They perceive not, or will not seem to perceive, that nothing which can be called Government ever was, or ever could be, in any instance, exercised, but at the expense of one or other of those rights.—That, consequently, in as many instance as Government is ever exercised, some one or other of these rights, pretended to be unalienable, is actually alienated.

“Inalienable rights” passages in selected constitutions from other states

Illinois Constitution of 1870:

All men are by nature free and independent, and have certain inherent and inalienable rights — among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. To secure these rights and the protection of property, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Pennsylvania Constitution of 1874:

All men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent and indefeasible rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, of acquiring, possessing and protecting property and reputation, and of pursuing their own happiness.

Missouri Constitution of 1875:

That all constitutional government is intended to promote the general welfare of the people; that all persons have a natural right to life, liberty and the enjoyment of the gains of their own industry; that to give security to these things is the principal office of government, and that when government does not confer this security, it fails of its chief design.

Colorado Constitution of 1876:

That all persons have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.

Missouri Constitution of 1945:

That all constitutional government is intended to promote the general welfare of the people; that all persons have a natural right to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and the enjoyment of the gains of their own industry; that all persons are created equal and are entitled to equal rights and opportunity under the law; that to give security to these things is the principal office of government, and that when government does not confer this security, it fails in its chief design.

Hawaii Constitution of 1950:

All persons are free by nature and are equal in their inherent and inalienable rights. Among these rights are the enjoyment of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and the acquiring and possessing of property. These rights cannot endure unless the people recognize their corresponding obligations and responsibilities.

Virginia Constitution of 1971:

That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Sources

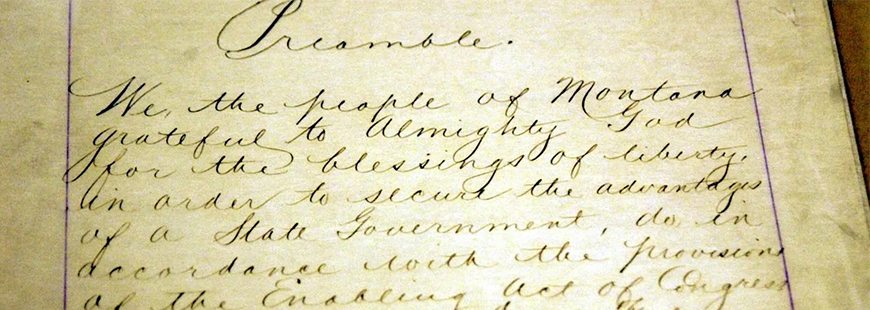

Draft Montana Constitution of 1884:

Article I Section 3:

That all persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.

Montana Constitution of 1889:

All persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness in all lawful ways.

The 1889 Constitutional Convention

July 18, 1889 – Committee of the Whole reads the draft art. 3 Section 3: “That all persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness in all lawful ways.” No amendments are offered.

July 18, 1889 – Committee of the Whole. Mr. Sargent of Silver Bow [objecting to a different constitutional provision prohibiting armed persons from being brought into the state to keep the peace]: “Mr. Chairman, Article 3 of our Bill of Rights says, ‘All persons are born equally free to have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their rights and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property,’ etc. . . . I say that it would be an infringement on his rights that he should not go anywhere to seek that protection that he is entitled to have under the Constitution of the State, and I am certainly opposed to the resolution for this reason.”

July 23, 1889 – final text of art 3. Sec. 3 read and not amended.

July 23, 1889 – delegates vote on text of Bill of Rights, adopt it by vote of 66-1.

Other Sources

From Study No. 10 for the Montana Constitutional Convention

“The [1889] Montana Constitution contains the following provisions [including art. III, § 3] which basically are expressions of political theory. . . . There is some question as to the propriety of retaining such statements of political theory in the declaration of rights. Their argument for their exclusion goes something like this: statements of political theory are hortatory, generally are not the subject of judicial interpretation and therefore are unenforceable. . . . This argument sounds even more plausible if one agrees that the judicial enforceability of the various civil liberties provisions is the main source of their capacity to limit government.”

“Given the outcome of the colonial insistence (separation from England and a revolution), it becomes clear that there is a closer than imagined relationship between the enunciation of supposedly unenforceable political theories and ideas and the sifting and distillation of these notions into concrete, even commonplace, legally enforceable doctrines.”

“Inalienable rights are thus held to be prior to government and not subject to any governmental power.”

“Putting their [Colonists’] rights to parchment did not create them; it only affirmed their existence[.]”

“If a right is inalienable, it is not the kind which a temporal government can grant or take away. Such inalienable rights were not part of the social contract ‘bargain’: government could at best secure them, but it could provide no substitute for them or impetus to trade them away.”

“Short lists (such as Jefferson’s) of the most basic inalienable rights, seemingly so broad as to find the approval of all, have a long history of evolving in the name of a number of political positions in heated conflicts and controversies. They also have many implications which are far beyond the bounds of this report. What is certain is that only the tip of the iceberg is seen in such constitutional expressions as that in the [1889] Montana Constitution [art. III, § 3].

Drafting

From Delegate Proposal No. 12 for a new constitutional article regarding the environment, introduced by Jerome J. Cate, January 21, 1972:

Section 3. RIGHTS OF INDIVIDUALS. Each person has an inalienable right to the unimpaired enjoyment of this public trust and shall be entitled to enforce this right on his own behalf and on behalf of others against any entity through appropriate legal proceedings.

From Delegate Proposal No. 20 for a new constitutional article regarding natural resources, introduced by C.B. McNeil, January 25, 1972:

Section __. ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY. It is the public policy of the State of Montana and the duty of each person to provide, maintain, and enhance a quality environment for the benefit of the people.

From Delegate Proposal No. 21 for a new section to former Article III, Bill of Rights, introduced by C.B. McNeil, January 25, 1972:

Section 32. It is the right of each person to have, and the duty of each person to maintain and enhance, a quality environment.

From Delegate Proposal No. 43 for revisions to former Article III, Section 3, Bill of Rights, introduced by Lyle R. Monroe, Richard B. Roeder, Bob Campbell, Dorothy Eck, Harold Arbanas, Lucile Speer, and Virginia H. Blend, January 27, 1972:

Section 3. All persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned are the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, the right to the basic necessities of life including the right to adequate nourishment, housing, and medical care, of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness in all lawful ways.

From Delegate Proposal No. 93 for revisions to former Article III, Section 3, Bill of Rights, introduced by Henry Siderius and Douglas Delaney, February 2, 1972:

Section 3. All persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, of collective bargaining to achieve a fair and just return for what they produce, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness in all lawful ways.

From Delegate Proposal No. 116 for revisions to former Article III, Section 3, Bill of Rights, introduced by J.K. Ward and 18 others, February 3, 1972:

Section 3. All persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness in all lawful ways. All people are free by nature and are equal in their inherent and inalienable rights. Among these rights are the enjoyment of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. These rights cannot endure unless people recognize their reciprocal responsibilities and obligations to secure and preserve these rights and to protect their property.

Bill of Rights Committee Report, February 22, 1972:

Draft of Article II, Section 3:

Section 3. INALIENABLE RIGHTS. All persons are born free and have certain inalienable rights which include the right of pursuing life’s basic necessities, of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, of acquiring, possessing and protecting property and of seeking their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways. In enjoying these rights, the people recognize corresponding responsibilities.

Ratification

Voters approve the 1972 Constitution

Ellis Waldron's "Montana Public Affairs" Report Number 12 from June of 1972 cites an approval rate of "slightly more than one-half of one percent of the total vote on the issue." Voters approved the Montana Constitution "by a vote of 116,415 to 113,883. The 1972 Constitution was ultimately approved by 2,532 votes.

The 1972 Voter Information Pamphlet

Article II DECLARATION OF RIGHTS:

Retained From Present Constitution:

"No rights protected by the present Montana Declaration of Rights are deleted or abridged in the proposed Constitution. These include the freedom of speech, assembly and religion; the right to self government; the right to acquire, possess and protect property; the right to suffrage; right to bail, and right to a trial by jury, among others. In addition the present Montana provision guaranteeing the right to keep and bear arms is retained in total."

New Provisions Added:

"In addition to retention of all rights protected by the present Constitution, the proposed document would protect the:

Right to pursue a clean and healthful environment. Section 3

Right to know (including the right to attend meetings of public agencies and to examine the agency's records), except when the demand of individual privacy clearly exceeds the merits of public disclosure. Section 9

Right of privacy. Section 10

Right to sue the state and its subdivisions for injury to person or property. Section 18

Right of participation. Government agencies must allow citizen access to the decision making institutions of state of government. Section 8

Right against discrimination in the exercise of civil and political rights. Section 4

Rights of persons under the age of majority (lowered to 18). Sections 14 and 15."

Interpretation

Right to a Clean and Healthful Environment

1999: Montana Environmental Information Center (MEIC) v. Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

"Although Article IX, Section 1(1), (2), and (3) were all approved by the convention on March 1, 1972 (Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. V at 1251, 1254-55, March 1, 1972) the right to a clean and healthful environment was not included in the Bill of Rights until six days later on March 7, 1972. On that date, Delegate Burkhart moved to add “the right to a clean and healthful environment” to the other inalienable rights listed in Article II, Section 3 of the proposed constitution. Montana Constitutional Convention, Vol. V at 1637, March 7, 1972."

Montana Envtl. Info. Ctr. v. Dept. of Envtl. Quality, 296 Mont. 207, 229 (1999).

"Applying the preceding rules to the facts in this case, we conclude that the right to a clean and healthful environment is a fundamental right because it is guaranteed by the Declaration of Rights found at Article II, Section 3 of Montana's Constitution, and that any statute or rule which implicates that right must be strictly scrutinized and can only survive scrutiny if the State establishes a compelling state interest and that its action is closely tailored to effectuate that interest and is the least onerous path that can be taken to achieve the State's objective."

Montana Envtl. Info. Ctr. v. Dept. of Envtl. Quality, 296 Mont. 207, 225 (1999)

[R]ight to pursue life's basic necessities

1996: Wadsworth v. State, 275 Mont. 287.

"While not specifically enumerated in the terms of Article II, section 3 of Montana's constitution, the opportunity to pursue employment is, nonetheless, necessary to enjoy the right to pursue life's basic necessities."

Wadsworth v. State, 275 Mont. 287, 298.

[R]ight to enjoy and defend their lives and liberties

The Montana Supreme Court has not yet addressed a constitutional right to defend lives and liberties in the context of Article II section 3. However, Mont. Code Ann. Section 45-3-101et. seq. does define the "Justifiable Use of Force."

[Right to] acquire, possess and protect property, and [to] seek their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways

2012: Montana Cannabis Indus. Ass'n v. State, 366 Mont. 224

"[T]he idea that the right to pursue employment and life's other ‘basic necessities' is limited by the State's police power is imbedded in the plain language of the Constitution. Article II, Section 3 states that citizens have the right to pursue ‘life's basic necessities ... in all lawful ways."

Montana Cannabis Indus. Ass'n v. State, 366 Mont. 224, 230 (2012).

"The fundamental right to seek health is found in Article II, Section 3 of the Montana Constitution and provides that Montanans have a fundamental right to “seek[ ] their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways.” (Emphasis added.) As with the right to pursue employment, the Constitution is clear that the right to seek health is circumscribed by the State's police power to protect the public's health and welfare."

Montana Cannabis Indus. Ass'n v. State, 366 Mont. 224, 231 (2012)

Committee Commentary

The committee proposes with two dissenting votes that the former Article III, section 3 be retained with a few substantive changes. The committee struck language which was felt to be redundant. In addition, it is recommended that the right to pursue life’s basic necessities be incorporated as a statement of principle. The intent of the committee on this point is not to create a substantive right for all for the necessities of life to be provided by the public treasury.

The committee heard considerable testimony, from low income and social services people alike, that the state’s current public assistance programs are not meeting the genuine needs of low income people who, because of circumstances beyond their control, are unable to obtain basic necessities. Accordingly, it is hoped that the legislature will have occasion to review these programs and upgrade them where necessary to provide full necessities to those in genuine need and to curb whatever abuses may exist in the programs.

What was attempted in this part of the proposed section was a statement of the principle that all persons have the inalienable right to pursue the basic necessities of life—that there can be no right to life apart from the possibility of existence.

The other inalienable rights were included with only minor changes in style for purposes of clarity. An additional right, the right of seeking health was incorporated in recognition of the fact that a right to life without health is a sorry proposition.

The final sentence of this section is new having been derived from delegate proposal No. 116. Testimony was received both favoring and opposing the inclusion of a statement of corresponding responsibilities in the declaration of rights. Some expressed the feeling that many were accepting rights without recognizing that they create obligations. Others were adamant that a declaration of rights should contain just that: the rights of persons against governmental abuses and the rights of minorities against the power of unchecked majorities. The committee felt that the inclusion of such a statement does not infringe or impair the rights granted in the declaration of rights but only accords a tone of responsibility to their exercise.

A number of delegate proposals were rejected in the drafting of this section. Delegate proposal No. 45 stipulated a substantive right to the necessities of life. No. 93 proposed an inalienable right to collectively bargain. The committee felt that the issue of collective bargaining—as well as its counterpart the right to work—were properly statutory matters.

Floor debate regarding constitutional provision on the Article IX right to a clean and healthful environment, March 1, 1972:

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Very well, the issue is on Mrs. Robinson’s proposal to amend Section 1 of the environmental part of the Natural Resources proposal. Mrs. Robinson, are you ready to close? DELEGATE ROBINSON: Mr. President, I would like to just briefly reiterate some of the comments that have been made since I last spoke. Mr. Garlington brought up the usage of some of these words. It reminds me of the last hearing that the Natural Resources Committee had . . . an attorney from Helena, Mr. Picotte, who represented North Dakota Utilities, was also concerned about the words “clean”, “healthful”, “quality”, because they were too metaphysical-if you will remember that terminology. Mr. Garlington’s objections seemed to be very similar to me. We are worried about someone being able to interpret these words. . . . Further, I’d like to indicate to you that in the Bill of Rights, in the present and the proposed, we have certain metaphysical terms such as “inalienable rights”, which include “the right of pursuing life’s basic necessities” or “of enjoying or defending their lives and liberty”, “of acquiring, possessing and protecting property”, and “of seeking their safety, health, happiness in all lawful ways”. These are pretty metaphysical terms, too, it seems to me. But it seems that, judging by contemporary community standards, we’ve had no trouble in determining what “liberty” means, what “freedom”, what “inalienable rights” mean. I submit that we are not going to have any trouble in determining what “clean” and “healthful” and “high-quality” means.

Floor debate regarding Bill of Rights committee report, March 7, 1972:

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: . . . Section 3-please read, Mr. Clerk.

CLERK HANSON: Mr. Chairman. “Section 3, Inalienable rights. All persons are born free and have certain inalienable rights, which include the right of pursuing life’s basic necessities; of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; and of seeking their safety, health, and happiness in all lawful ways. In enjoying these rights, the people recognize corresponding responsibilities.” Mr. Chairman, Section 3.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Monroe.

DELEGATE MONROE: Mr. Chairman. I move that when this committee does arise and report, after having under consideration Section 3 of Proposal Number 8, it recommends that the same be adopted. Mr. Chairman.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Monroe.

DELEGATE MONROE: In the inalienable rights section, we have basically kept it the same as the inalienable rights section in our present Constitution, except for some minor changes. If you’ll turn to page 15 in our committee proposal, you can read along with me. The committee proposes, with two dissenting votes, that the former Article III, Section 3, be retained with few substantive changes. The committee struck language which was felt to be redundant. In addition, it is recommended that the right to pursue life’s basic necessities be incorporated as a statement of principle. The intent of the committee on this point is not to create a substantive right for all the necessities of life to be provided by the public treasury. The committee heard considerable testimony from low-income people and social service people alike that the current state public assistance programs are not meeting the genuine needs of low-income people who, because of circumstances beyond their control, are unable to obtain basic necessities. Accordingly, it is hoped that the Legislature will have occasion to review these programs and upgrade them where necessary to provide full necessities to those in-who-in genuine need and to go-and to curb whatever abuses may exist in the programs. What was attempted in this part of the portion-the proposed section was a statement of principle that all persons have inalienable right to pursue the basic necessities of life, that there can be no right to life apart from the possibility of existence. Other inalienable rights were indicated, with only minor changes in style for purposes of clarity. In addition, an additional right, the right of seeking health, was incorporated in recognition of the fact that the right to life without health is a very sorry proposition. The final sentence of this section is-having been derived from Delegate Proposal Number 116. Testimony was received both favoring and opposing the inclusion of this statement of corresponding responsibilities in the declaration of rights. Some expressed the feeling that many were accepting rights without recognizing that they create obligations. Others were adamant that a declaration of rights should contain just that-the right of persons against governmental abuses and the rights of minorities against the power of unchecked majorities. The committee felt that the inclusion of such a statement does not infringe or impair the rights granted in the declaration of rights, but only accords a tone of responsibility in their exercise, In regard to basic necessities, we had about 17 people come before our committee. Many of them were of low income status economically, and we had social service workers. And it was our opinion that such a statement in the Bill of Rights as we have stated here does not suggest that the state pay out of the public treasury for those basic necessities, such as housing, medical care and nourishment, but that this is more or less a constitutional sermon so that maybe the Legislature, from time to time, can improve and update--update and upgrade our public assistance programs from time to time as they see fit. Of course, the right to health was incorporated in the last sentence and the second to the last sentence of our inalienable rights section. I didn’t look it up in the dictionary; but an inalienable right is something, in my estimation, that comes to each one of us just because we’re here and we’re human beings. Even if there was no such thing as a government, all of us would have these rights. I will stop at this point, and if there’s any comments we can hear them, and I move that we adopt this section. Thank you.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Is there further debate? Mr. Kelleher. No? Mr. Burkhardt.

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: I believe that you have, Mr. Chairman, a copy of an amendment for this section that does not delete anything. It’s the addition of eight words, and I wonder if the clerk could read it.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Will the clerk please read Mr. Burkhardt’s amendment.

CLERK HANSON: “Mr. Chairman. I move to amend Section 3, Bill of Rights Committee proposal, on page 4, line 26, by inserting, after the word ‘include’, the following words-quote: ‘the right to a clean and healthful environment’- comma, end quote. Signed: Burkhardt.”

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: Mr. Chairman.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Just a moment. Mr. Burkhardt wishes to make an amendment on line 26, after the word “include”, right at the end of the line-“which include”--and he wants to add the words “the right to a clean and healthful environment” before the phrase “the right to pursuing life’s basic necessities”, et cetera. Mr. Burkhardt, your amendment is allowed. Go ahead and discuss it.

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: Mr. Chairman. This is a statement that we, as a body, have already adopted in another section of our Constitution, in our Natural Resources section. We have the statement: “It shall be the duty of the State of Montana and each person to maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment.” And it seems to me that it’s simply striking the other side of the balance to put it here in our Bill of Rights, to recognize that this is, for the time in which we’re living and for the foreseeable future, one of the inalienable rights that we hope to assure for our posterity. I don’t care to belabor the issue. It seems to me it’s self-evident. I would reserve the right to close if there is debate on the issue.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Dahood.

DELEGATE DAHOOD: Mr. Chairman, I would ask Delegate Burkhardt if he will yield to a question.

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: I will.

DELEGATE DAHOOD: Delegate Burkhardt, I would like to inquire, on behalf of our committee, if by this proposed amendment it is your intention to provide the citizens of the State of Montana with the independent right to initiate a lawsuit when his own health and his own property is not affected within the contemplation of the present law?

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: Mr. Dahood, you have much experience as a trial lawyer and I may be somewhat at a disadvantage in handling the question, but I will try to answer it as I understand it. I read the Preamble to this section on the Bill of Rights and believed it. I think it’s a beautiful statement, and it seems to me that what I am proposing here is in concert with what’s proposed in that Preamble; that what we are talking about here is the goal toward which we try to grow as a society. I do not see it as an overt attempt to slip in with the opportunity to sue.

DELEGATE DAHOOD: Very fine. Thank you very much. Mr. Chairman, I certainly want to comment that, with respect to the basic concept itself, it is a concept with which no one can disagree, in my judgment, but I certainly would like to hear some of the other delegates with respect to the proposed amendment. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Is there further discussion? Mrs. Eck.

DELEGATE ECK: Our Bill of Rights Committee discussed environmental issues at some length and decided that we really shouldn’t include a section on environmental bill of rights, which I think that a great many of us had expected to do, since this would be covered by the Natural Resources Committee. We did submit a statement to the Natural Resources Committee which included, I think, a slightly stronger statement than what we’ve included here. We also concurred pretty much with the statement that they came up with, especially their statement of what the duty of the state is in regards to maintaining a clean environment, a healthful environment, a high quality environment-whatever you want to call it. It’s my understanding that they quite purposely did not include a statement of each individual’s rights, believing that this kind of a statement really fitted better into the Bill of Rights. We could include a separate statement on it, but I think that with what has gone before, it’s not really necessary; and I certainly do concur in Mr. Burkhardt’s amendment here as being quite appropriate to what the intention of it was in our committee and I think also the intention of the Natural Resources Committee. Thank you.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Is there further discussion? Mr. Toole.

DELEGATE TOOLE: Mr. Chairman, would Mr. McNeil yield to a question on this subject?

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. McNeil?

DELEGATE McNEIL: I yield.

DELEGATE TOOLE: Mr. McNeil, do you think this tends to reinforce your article in Natural Resources, or how do you regard putting this in with-in the light of what your own committee did?

DELEGATE McNEIL: I can’t speak for the committee; I can only speak as an individual. I introduced a delegate proposal which would have given each individual the right to a quality environment. I have already spoken on this “clean and healthful”. I’m afraid that that isn’t as strong as what we really want, but if that’s the will of the Convention and as strong as they think they can pass, why, I would agree with it.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Dahood.

DELEGATE DAHOOD: Well, Mr. Chairman, I would want the minutes and the record of this Convention to show that this amendment does not have as one of its purposes an attempt to circumvent the votes that were taken with respect to the Natural Resources motions that attempted to put in theories with respect to the environment, that were rejected by a majority of these constitutional delegates. And I trust that this is not the intention of the mover of the amendment; and if that be correct, then I would have no objection to the amendment.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Burkhardt, do you care to respond?

DELEGATE BURKHARDT: Am I closing or just responding, or what?

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Well, you’re probably closing, since I don’t see anyone else up. DELEGATE BURKHARDT: The way I figure it, Bob Kelleher owes all of us an hour and a half, and one of these days I’m going to take it, but not now. (Laughter) Just that I think running through all of us is a concern to provide for future years, and I think industry joins us in this concern. They are, after all, human beings whose children must grow up in our country; and already our major industries are on record in the direction and beyond what we’re stating here. So I would say that I did not vote the other day for the public trust concept because I felt it had been an emotional, a distorted issue and that it would be misunderstood; and it seems to me that we are providing here, though, a clear intent. It does present the right of every person. And we’ve already talked about the duties of persons, and it’s nice to balance it with this right. I close with that.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Very well, the issue arises on Mr. Burkhardt’s motion to add the terms-the words “the right to a clean and healthful environment” on line 26, page 4, of the Bill of Rights Article, Section 3. So many—

DELEGATE KAMHOOT: Roll call.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Kamhoot wants a roll call vote. So many as are in favor of Mr. Burkhardt’s amendment, vote Aye; so many as are opposed, vote No. Have all the delegates voted? [...]

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: 79 delegates having voted Aye and 7 No, the amendment to add that phrase to Section 3 passes-or is adopted. Is there any other discussion of Section 3? Mr. Kelleher.

DELEGATE KELLEHER: Mr. Chairman, I move to substitute the word “conceived” for the word “born” on line 25. Mr. Chairman.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Just a minute, Mr. Kelleher. Since you didn’t send that up, I have to write it out here.

DELEGATE KELLEHER: C-O-N-C-E-IV-E-D.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: B-O-R-N? Yes, Mr. Kelleher. Mr. Kelleher makes a motion to amend line 25 by striking the word “born” and putting in the word “conceived”.

DELEGATE KELLEHER: Mr. Chairman.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Kelleher.

DELEGATE KELLEHER: My purpose in this is, what’s the use of having rights of the living if I don’t have the right to be born? A most defenseless human being in the world is the human fetus, which is dependent upon its own mother for protection. And lastly, I would leave to the courts the meaning of when a-quote-“person’‘-close quote-as used in line 25, is conceived.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Mr. Dahood.

DELEGATE DAHOOD: Mr. Chairman, I stand in opposition to the amendment. What Delegate Kelleher is attempting to do at this time is, by constitutional command, prohibit abortion in the State of Montana. That issue was brought before the committee. We decided that we should not deal with it within the Bill of Rights. It is a legislative matter insofar as we are concerned. The world of law has for centuries conducted a debate as to when a person becomes a person, at what particular state, at what particular time; and we submit that this particular question should not be decided by this delegation. It has no part at this time within the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the State of Montana, and we oppose it for that reason.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Very well, Mr. Kelleher, you may close.

DELEGATE KELLEHER: May I have five seconds, please, for a roll call vote?

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: All right, we’ll have a roll call vote. The question now arises on Mr. Kelleher’s amendment to substitute the word “conceived” for the word “vote’‘-or for the word “born”. So that the first sentence would read: “All persons are conceived free and have certain inalienable rights.” So many as shall be in favor of Mr. Kelleher’s motion, vote Aye; and so many as shall be opposed, vote No. Has every delegate voted? (No response)

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Does any delegate wish to change his vote? (No response) [...]

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: 71 having voted No and 15 delegates having voted Aye, Mr. Kelleher’s motion fails. Is there other discussion of Section 3? (No response) Very well, members of the committee, you have before you, on the recommendation of Mr. Monroe that when this committee does arise and report, after having had under consideration Section 3, that it recommend the same be adopted as amended. So many as shall be in favor of that motion, say Aye.

DELEGATES: Aye.

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Opposed, No. (No response)

CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Section 3 is adopted.

Floor debate regarding the death penalty, March 9, 1972:

DELEGATE HARBAUGH: [...] And then, there’s another thing I really think that’s kind of interesting in this thing. When you gave the right in your Constitution for anyone to give--use sufficient force to enforce-to protect his own life and his own property, you, in a sense, said you can shoot somebody in self defense, and that’s a death penalty in reverse. In other words, you wouldn’t want to take that right away to protect your wife and your children and your property.

Report of Committee on Style, Drafting, Transition and Submission, March 13, 1972:

Draft of Article II, Section 3:

Section 3. INALIENABLE RIGHTS. All persons are born free and have certain inalienable rights. They include the right to a clean and healthful environment and the rights of pursuing life’s basic necessities, enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and seeking their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways. In enjoying these rights, all persons recognize corresponding responsibilities.

Comments on Style, Form, and Grammar:

Section 3. Structural changes serve clarity without altering substance.

Floor debate regarding constitutional provision on public assistance, March 14, 1972:

DELEGATE MONROE: Mr. McNeil, I’m wondering--a person that is an invalid in the Cascade County Convalescent Home, for example, that is on assistance; would you require them to earn their keep? DELEGATE MCNEIL: Of course not, Mr. Monroe. It says “the Legislature provide the opportunity”. If they’re incapacitated, they obviously would not have to work. The amendment is intended and directed to those who are physically able and capable of working who do not do so. [...] DELEGATE MONROE: Do you think every able-bodied person that is, let’s say, even temporarily on assistance should be made to earn that assistance? DELEGATE MCNEIL: Mr. Chairman, the proposed amendment provides that the opportunity to earn should be presented to them, and if the opportunity to earn their economic assistance is made available and they are physically able, I would say “Yes, they ought to before they receive it.” [...] DELEGATE MONROE: I would oppose this amendment to this particular article. It seems to me we’ve kind of covered it in our Section 3 of our Bill of Rights. We’ve suggested there that people have a right to pursue some of the basic necessities, and in that same section we also are suggesting that the people have a duty and responsibility--or corresponding responsibility, there-to take some sort of responsibility-for example, if they are receiving assistance. I don’t agree with the idea that people should have to work for, let’s say, welfare benefits, and I don’t disagree with it either; but I know the problems that exist right now. If we’re suggesting that people that are on assistance at this time go out and work for it, I think that’s a great idea, and it has happened in many occasions in many of the counties in the State of Montana. The fact is that you . . . [ ]tions, in many cases, because you run into union conflicts; and you would probably run into the same if you require assistance recipients to work for benefits there. It’s a beautiful and a great idea, but it’s rather impractical to implement. So I resist this particular amendment.

Floor debate regarding an amendment to the article on Labor of the Public Health, Welfare, Labor and Industry Committee Report by adding a new section requiring retail stores to be closed on Sundays, March 15, 1972:

DELEGATE DAVIS: [...] And although I am not a Seventh Day Adventist, this is a great infringement on the rights of-the religious thinking of people who do worship on a different day than Sunday. And I do suggest that it’s probably a violation of Section 3 of the Bill of Rights, which provides all people are born free and have certain inalienable rights, which include the right of pursuing life’s basic necessities. So I think this should be defeated. It’s not the type of thing-it’s an infringement on the rights of any Seventh Day Adventist who take their day off on Saturday, and if they wish to work on Sunday, they have that right.

Committee of the Whole debating a report from the Style and Drafting Committee, March 16, 1972:

CLERK HANSON: “Section 3, Inalienable rights.” Mr. Chairman. DELEGATE SCHILTZ: Mr. Chairman. I move that when this committee does arise and report, after having had under consideration Section 3, Style and Drafting Report Number 8, it recommend the same be adopted. Mr. Chairman, minor style changes. I have a note I want to check, though. Oh, you’ll notice on page 10, line 2, we changed “the people” to “all persons”, for the reason that they are doing some relating one to another and it’s pretty hard for the people to relate. So we changed it to “All persons recognize corresponding responsibilities”. CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Is there any discussion of Section 3? All in favor of Section 3, say Aye. DELEGATES: Aye. CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Opposed, No. (No response) CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: It’s adopted.

Floor debate and vote on specific provisions [March 18, 1972]:

Delegates’ vote on Article II, Section 3 was held on March 18, 1972. Article II, Section 3 passed by a vote of 91-2. Five delegates were absent, and two were excused.

Floor debate on [March 18, 1972]:

DELEGATE ARONOW: [. . .] This morning we adopted, on third reading, Section 3 of the Bill of Rights, the rights and this is one of the individual rights-the rights of pursuing life’s basic necessities. We’re not here to play God, to take away a man’s livelihood, take away his office; he had a right to rely upon it. We did eliminate one office-that’s the State Treasurer-but that treasurer is not able to run to succeed himself, so we did not deprive anyone of the right to make a living or the right to hold a job.

Style and drafting committee unanimously approves Article II, March 21, 1972:

CLERK HANSON: “Article II, Declaration of Rights,” page 3. Mr. Chairman. DELEGATE SCHILTZ: Mr. Chairman, I move when this committee does arise and report, after having had under consideration Article II, Final Report, Style and Drafting Committee, it recommend the same be adopted. Mr. Chairman, we have no changes in the Bill of Rights in Article II. CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Article II contains 35 sections. Is there any discussion of Article II? It has no changes. (No response) CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: All in favor of Article II, say Aye. DELEGATES: Aye. CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: Opposed, No. (No response) CHAIRMAN GRAYBILL: It’s adopted.

Delegates vote on Article II, March 22, 1972:

Delegates’ vote on entirety of Article II was held on March 22, 1972. Article II passed by a vote of 92-3. Four delegates were absent, and one was excused.

Subsequent Commentary

From April to June of 1972 The Billings Gazette published a series of 30 articles by staff writers in the Opinion section designed to inform voters about changes to their Constitution.

The fourth article in the series from May 2, 1972 was entitled "More protection for the individual." The article's opening paragraph stated, "Framers of the proposed 1972 Montana Constitution which will be voted on June 6 took some giant strides forward for mankind or entered fields into which no constitution should delve. It depends on how you look at their Declaration of Rights."

The fifth article in the series from May 3, 1972 was entitled "What's new in '72." This article's opening paragraph stated, "Did Montana's 1972 Constitutional Convention delegates get carried away when they launched into new protection rights?"

Both articles examine individual rights based on hypothetical situations that could either help or hurt Montanans in the long run. Both articles however, begin from the premise that individual inalienable rights set forth in the proposed constitution depart significantly from the status-quo.