II.4 Individual Dignity

Text

"Section 4. Individual dignity. The dignity of the human being is inviolable. No person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws. Neither the state nor any person, firm, corporation, or institution shall discriminate against any person in the exercise of his civil or political rights on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas."Mont. Const. art. II § 4.

History

Sources

1884 Proposed Montana Constitution

The 1884 Proposed Montana Constitution did not acknowledge individual dignity or equal protection, but provided that "all persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.Proposed 1884 Mont. Const. art. I § 3: https://archive.org/stream/montanaconstitutmontrich#page/5/mode/2up

The 1884 Proposed Montana Constitution did contain an equal protection concept in Article XV, § 7: "All individuals, associations, and corporations shall have equal rights to have persons or property transported on and over any railroad, transportation or express route in this State. No discrimination in charges, or facilities for transportation of freight or passengers of the same class, shall be made by any railroad or transportation, or express company between persons or places within this State[.]" Proposed 1884 Mont. Const. art. XV § 7: https://archive.org/stream/montanaconstitutmontrich#page/30/mode/2up

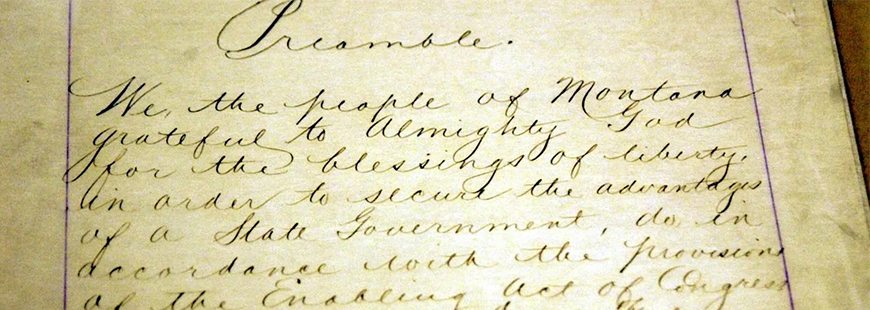

1889 Montana Constitution

The 1889 Montana constitution was ratified to include the exact same language as the proposed 1884 constitution:

"all persons are born equally free, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness."1889 Mont. Const. art. III § 3: https://archive.org/stream/constitutionofst00montrich#page/n7/mode/2up/

"All individuals, associations, and corporations shall have equal rights to have persons or property transported on and over any railroad, transportation or express route in this State. No discrimination in charges, or facilities for transportation of freight or passengers of the same class, shall be made by any railroad or transportation, or express company between persons or places within this State[.]" 1889 Mont. Const. art. XV § 3: https://archive.org/stream/constitutionofst00montrich#page/n41/mode/2up/

Federal Constitution

There is no right of individual dignity in the Federal Constitution, but equal protection is derived from the Fourteenth Amendment: "Amendment XIV Section 1.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." U.S. Const. amend. XIV.

Puerto Rico Constitution

At the time of the 1972 Constitutional Convention, the delegates on the Bill of Rights Committee were drafting Article II, Section 4 from scratch, their guides: state constitutional comparisons. Delegate Proposal 61 was forwarded to the Bill of Rights Committee by Delegate Richard Champoux, the Chairman of the Education and Public Lands Committee, as the “single provision of the 1972 Convention of which he was most proud.” Matthew O. Clifford and Thomas P. Huff, Some thoughts on the Meaning and Scope of the Montana Constitution's Dignity Clause with Possible Applications, 61 Mont. L. Rev. 301, 321, footnote 92 (2000). The language of Champoux’s proposal was borrowed from a similar provision in another constitution, ratified just some twenty years before, in Puerto Rico. Section 4 was derived almost entirely from the equal rights provision of the Puerto Rico Constitution, available to the delegates in the text of the Comparison of the Montana Constitution with the Constitutions of Selected Other States, a report prepared by the Constitution Revision Commission and republished by its successor, the Constitutional Convention Commission. The Commission, created by the 1971 Legislative Assembly, was tasked with compiling “historical, legal and comparative information about the Montana Constitution” in preparation for the delegates' work at the upcoming convention. Comparison of the Montana Constitution with the Constitutions of Selected Other States, Occasional Paper No. 5, iii-iv (1971-72).

Enabled by the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act of 1950, Puerto Rico held its own constitutional convention from September 1951 to February 1952. The result was the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, ratified by Puerto Ricans and approved by the United States months after the convention. Borrowing from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948, Puerto Rico’s Constitution identifies individual dignity as the keystone of its entire structure, and its special place in the Bill of Rights reflects international changes in a post-World War II attitude toward human rights and democracy. Vicki C. Jackson, Constitutional Dialogue and Human Dignity: States and Transnational Constitutional Discourse,, 65 Mont. L. Rev., at 22-25 (2004).

The Puerto Rico Constitution’s Article II, Section 1 reads:

“The dignity of the human being is inviolable. All men are equal before the law. No discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, sex, birth, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas. Both the laws and the system of public education shall embody these principles of essential human equality.” Comparison, supra note 8, at 32A.

Drafting

Background: The Constitution Revision Commission

By the late 1960’s Montana’s nearly eighty-year-old Constitution was due for a revision. The Constitution Revision Commission was established to “study the Montana Constitution”, begin drafting a proposed constitution, and report to the Legislative Assembly “any proposal for change".Constitutional Provisions Proposed by Constitution Revision Commission Subcommittees, Occasional Paper No. 7, preface (1971-72). The Legislative Council Subcommittee on the Constitution, a subcommittee of the Constitution Revision Commission, prepared a series of reports to be presented for deliberation in December 1969. Among these reports were a comparison of Montana’s Constitution with those of six other states, preliminary comments on each section of the existing Constitution, and proposed amendments. The Constitution Revision Commission’s goal was not to re-draft the constitution, but to evaluate its “adequacy.” Comparison, supra note 8, at iii-iv. At deliberations, the following conclusions were reached regarding Montana’s 1889 Constitution:

- There was a need for “substantial revision and improvement.”

- A Constitutional Convention was “the most feasible and desirable method of changing the Constitution.”

- The Commission would cede to elected delegates the task of re-drafting.

- The Commission would implement a public information program to encourage Montanans to consider a constitutional revision.Proposed Provisions, supra note 11, at preface.

Less than one year after the Constitution Revision Commission determined Montana’s Constitution was in need of revision, Montanans came together in agreement, voting by referendum in November 1970 to call a constitutional convention. By early 1972, Montana’s Constitutional Convention was underway.

Delegate Proposals

New Constitutional Section:

#10 Virginia Blend; Rejected: “Section __. Equal rights. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the state of Montana on account of sex.”

#32 Mae Robinson (w/ Lucille Speer); Rejected: “Section __. “No person shall, because of race, color, national origin, creed, religion or sex be subjected to any public or private discrimination in political and civil rights, in the hiring and promotion practices of any employer, or in the sale or rental of property. These rights shall be enforceable without action by the legislative assembly. Persons aggrieved shall have access to the Courts to enjoin discrimination prohibited by this section.”

#50 Bob Campbell; Rejected: “Section __. The equal protection of the laws shall not be denied or abridged by the state or its units of local government on account of race, color, creed, national ancestry or sex.”

#51 Bob Campbell; Rejected: “Section__. All persons shall have the right to be free from discrimination on the basis of race, color, creed, national ancestry or sex in the hiring and promotion practices of any employer or in the sale or rental of property. These rights are enforceable without action by the legislature but the legislature may provide additional remedies for their violation.”

#61 Richard Champoux (w/ William Burkhardt, Marshall Murray, J. Mason Melvin, & Jerome Kate); Adopted in part: “Section__. The dignity of the human being is inviolable. No person shall be denied the equal protection of the law, nor be discriminated against in the exercise of his civil or political rights or in the choice of housing or conditions of employment on account of race, color, sex, birth, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas, by any person, firm, corporation, or institution; or by the state or any agency or subdivision of the state.”

The Bill of Rights Committee

Members

- Wade J. Dahood, Chairman; Anaconda, Deer Lodge County, District 19; Republican

- Chet Blaylock, Vice Chairman; Laurel, Yellowstone County, District 8; Democrat

- Bob Campbell; Missoula, Missoula County, District 18; Democrat

- Dorothy Eck; Bozeman, Gallatin County, District 13; Republican

- Donald R. Foster; Lewiston, Fergus County, District 10; Independent

- R.S. (Bob) Hanson; Polson, Lake County, District 17; Independent

- George H. James; Libby, Lincoln County, District 23; Democrat

- Rachelle K. Mansfield; Geyser, Chouteau County, District 14; Democrat

- Lyle R. Monroe; Great Falls, Cascade County, District 13; Democrat

- Marshall Murray; Kalispell, Flathead County, District 16; Republican

- Veronica Sullivan; Butte, Silver Bow County, District 20; Democrat

Issues Before the Committee / Citizens and Citizen Groups Heard

In Missoula, Montana on January 12, 1972, the Bill of Rights Committee held a hearing to solicit suggestions and hear rights issues on the minds of Montanans.Bill of Rights Committee Hearing Notes, January 12, 1972, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives. A pressing issue, which many Montanans wanted addressed in the new constitution, was women’s rights. Numerous organizations petitioned for a provision prohibiting discrimination based on sex, including the Montana Federation of Womens’ Clubs (represented at the hearing by Bess R. Reed, a 30-year supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment), The American Association of University Women (in a letter sent by Elaine White, Missoula Branch President), the Missoula Business and Professional Women’s Club, and the Missoula Soroptimist Club.Id. The Montana League of Women Voters regularly sent letters petitioning the Committee to be ever-mindful of the significance of individual liberty. Delegate Rachelle Mansfield, responsible for presenting Section 4 to the Convention floor, received letters of support and gratitude from Montanan women, many of which she kept and are now in the archives at the Montana Historical Society in Helena, Montana. Delegate Richard Champoux, proponent of Delegate Proposal 61, the proposal from which Section 4 was largely drawn, was motivated by the story of his own mother, the discrimination in employment and indignities she faced, and her belief that “men and women should be treated equally and with dignity.”Clifford, supra note 7, at 321, footnote 92.

Additionally, the Montana Chamber of Commerce expressed concerns that citizen members of labor unions may denied employment based on that membership.Statement to the Montana Constitutional Convention Bill of Rights Committee by the Montana Chamber of Commerce, February 3, 1972, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives. The Montana State AFL-CIO expressed similar concerns, and advocated for protection in Section 4 for workers who had entered into collective bargaining agreements.Comments and Suggestions Concerning Proposed Bill of Rights by Montana State AFL-CIO, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives.

Committee Meeting Minutes Excerpts Regarding Delegate Proposals

February 8, 1972:

- RE: Proposal #10, “Out, decided on 61 instead.”

- RE: Proposal #61, “after the word "right" on line 16, the Committee decided to add "or, but not limited to". This change will have to to be discussed. Birth [strike] add culture”

- RE: Proposal #32, "Out."Minutes, Bill of Rights Committee, February 8, 1972, 2, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives.

February 9, 1972:

- RE: Proposal #61, "Adopted, with modifications."

- RE: Proposal #50, "Out."

- RE: Proposal #51, "Out, included in 61."

- "The Committee met at 8:00 P.M. and drew up the rough draft of the Bill Of Rights...It was decided to give our rough draft to the press. We are to send it to all the editors in the state."Minutes, Bill of Rights Committee, February 9, 1972, 2-3, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives.

February 12, 1972:

- The “Romney Hearing”, a presentation to all the Delegates

- Rachelle Mansfield presented Section 4… “#4 would prevent discrimination to any person because of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political religious ideas…”Minutes, Bill of Rights Committee, February 12, 1972, 3, Bill of Rights Committee Meeting Minutes, SMF-32, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives.

Text of Final Proposal and Accompanying Committee Comments

Section 4. INDIVIDUAL DIGNITY. The dignity of the human being is inviolable. No person shall be denied the equal protection of the law, nor be discriminated against in the exercise of his civil or political rights on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas, by any person, firm, corporation, or institution; or by the state, its agencies or subdivision [sic].

Section 4 unanimously adopted (11 yaes) at Roll Call Vote.

The proposed Declaration of Rights was intended by the delegates to be a contemporary replacement of Art III of the 1889 Constitution; no existing rights were diminished at the expense of adding new protections.Bill of Rights Committee Proposal No. VIII, February 23, 1972, in II MONTANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION 618, (1972). In drafting Art II of the 1972 Constitution, the Delegates were motivated by a particular spirit: “…the guidelines and protections for the exercise of liberty in a free society come not from government but from the people who create that government.”Id. at 619.

Section 4 was a new provision of the Declaration of Rights, representing Montanans’ concerns for equal protection under the law and freedom from discrimination. The intent of the delegates was expressed in their comments to Section 4, which accompanied the Bill of Rights Committee’s Proposal and was presented to the other Con-Con Delegates prior to Article II’s being brought to the floor of the Convention.Id. at 628 The Committee’s unanimous adoption of Section 4 was intended to “[provide] a Constitutional impetus for the eradication of public and private discrimination based on race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas.”Id.

In the comments to the proposed Section 4, the delegates gave their audience insight into the nature of the classifications the new provision established. Classifications such as “race”, “color,” and “sex” maintained their traditional meanings. Newer classifications, meanwhile, reflected Montana’s inclusive spirit: “culture” was intended to protect those groups with distinct heritage, namely Montana’s Native Americans; “social origin or condition” was intended to protect from discrimination based on “status of income and standard of living”; and “political or religious ideas” was intended as a class to be protected from discrimination by “public and private concerns.”Id.

Style and Drafting Committee Comments on Text

The Style and Drafting Committee recommended the following revision of Section 4: "INDIVIDUAL DIGNITY. The dignity of the human being is inviolable. No person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws. Neither the state, nor any person, firm, corporation or institution shall discriminate against any person in the exercise of his civil or political rights on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas."Report of Committee on Style, Drafting, Transition and Submission on Bill of Rights No. VIII, March 13, 1972, in II MONTANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION 962 (1972).

Comments on Style, Form, and Grammar: Section 4. The word “law” was made plural to agree with the parent 14th Amendment. Alteration of the form, but not the substance, of the second sentence makes the prohibition crystal clear. Countless court decisions make plain that a prohibition directed against the “state” includes all its arms, including “agencies or subdivisions.”Id. at 967.

Debate on the Convention Floor

Beginning March 7, 1972, the Bill of Rights Committee brought its proposed Declaration of Rights to the floor of the Constitutional Convention, to be put to a vote. Delegate Wade Dahood, the Committee’s Chairman, introduced Article II to the convention delegates: “[the] proposed Bill of Rights for the state of Montana…promises to provide the citizens of the State of Montana with the finest, most expansive declaration of rights enacted by any state of the United States.”V MONTANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION; VERBATIM TRANSCRIPT 1634 (1972). Section 4’s proponent, Delegate Rachelle Mansfield, offered it to the Convention with the Delegate’s intent clearly stated: “The committee unanimously adopted this section with the intent of providing a constitutional impetus for the eradication of public and private discrimination based on race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas. The provision, quite similar to that of the Puerto Rico declaration of rights, is aimed at prohibiting private as well as public discrimination in civil and political rights.”Id. at 1642. Mansfield then went on to explain the inclusion of the classifications that Section 4 was intended to protect: “sex” was included in response to “considerable” citizen testimony and in anticipation of the federal equal rights amendment; “culture” was included specifically to protect Montana’s American Indians; “social origin or condition” was included to protect against discrimination based on “status of income or standard of living”; and “political or religious ideas” were included to ensure protection from discrimination based on a person’s ideas.Id.

Delegate Otto T. Habedank of the General Government and Constitutional Amendment Committee moved to omit the language “by any person, firm, corporation” because of a concern that this part of the provision would interfere with individual privacy, namely that the language would “prohibit organizations that are incorporated from limiting their membership.”Id.at 1642-43. Delegated Dahood responded by reassuring Habedank that it was not the intended purpose of Section 4 to restrict the conduct contemplated, but only to “remove the apparent type of discrimination that all of us object to with respect to employment, to rental practices, [and] to actual associationship matters public or matters that tend to be somewhat quasi-public.”Id. at 1643. Dahood explained that the purpose of Section 4 was “to provide that every individual in the State of Montana, as a citizen of this state, may pursue his inalienable rights without having any shadows cast upon his dignity through unwarranted discrimination.”Id. According to Dahood, the language of Section 4 was drafted to impose the same limitations on discrimination on both the “state and its agencies” and the “private agencies that live within the society of the State of Montana.”Id. After a roll call vote, Delegate Habedank’s amendment to delete the language “by any person, firm, corporation or institution” failed.Id. at 1646.

Delegate Jerome T Loendorf, Vice Chairman of the Legislative Committee and Style, Drafting and Transition Committee member, posed a question regarding the potential for redundancy in Section 4, remarking that everything following “equal protection of the law” would be subsumed by that language and was therefore, possibly unnecessary.Id. at 1643. Dahood’s response was that “perhaps sometimes the sermon that can be given by [the] constitution, as well as the right, becomes necessary.”Id. at 1643-44. There was also discussion about whether Section 4, as written, would be non-self-executing. Delegate Mae Robinson, Bill or Rights Committee member and proponent of the rejected Delegate Proposal 32, voiced her concerns, to which Dahood responded: “…constitutions are based on the premise that they are presumed to be self-executing, particularly within the Bill of Rights. If the language appears to be prohibitory and mandatory, as this particular section is intended to be, then in that event, the courts in interpreting the particular section are bound by that particular presumption and they must assume, in that situation, that it is self-executing.”Id. at 1644.

Voting and Convention Adoption

After all present Constitutional Convention Delegates were afforded an opportunity to question the Bill of Rights Committee Delegates Wade Dahood and Rachelle Mansfield, Section 4 was put to a vote on March 7, 1972. Its adoption by the Convention was unanimous.Id. at 1646.

Ratification

Article II, § 4 was ratified by the people of Montana as part of the proposed 1972 constitution. The 1972 Voter's Pamphlet noted the article as a new provision: "New provision prohibiting public and private discrimination in civil and political rights."http://www.umt.edu/law/library/files/1972voterspamphlet

Before the 1972 Constitutional Convention began, there was concern among the delegates that bad press could “destroy [its] acceptance by the people.”Letter from Leo Graybill to Delegate Rachelle Mansfield, December 8, 1971, The Rachelle Mansfield Papers, SC 1899, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives. For Convention President, Leo Graybill, Jr., "portraying the right feelings about the important work of [the] Convention" was of grave importance.Id. In a letter addressed to Delegate Rachelle Mansfield, Graybill wrote: "...while we are doing our work, as the Convention progresses, the people of Montana must be both informed and involved. We, as the people's delegates, will have a duty to talk about the issues; to inform, educate, lobby and debate, and to involve ourselves and others."Id.

In a memo to all delegates dated March 13, 1972, Graybill sought the formation of a Voter Information Committee and the preparation of a Voter Information Pamphlet, encouraged media participation by delegates, and suggested other avenues for educating Montanans in preparation for the vote scheduled in June, 1972.Memo to All Delegates from Leo Graybill, March 13, 1972, The Rachelle Mansfield Papers, SC 1899, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives. In the final days before ratification, John H. Toole, the Chairman of the Public Information Committee, urged individual delegates to “do battle with the onslaught now being waged against us by opponents of the Constitution.”Memo to All Delegates from John. H. Toole, Chairman of Public Information Campaign, May 31, 1972, The Rachelle Mansfield Papers, SC 1899, Montana Historical Society Research Center, Archives. His call to action implored delegates to set up and run films continuously in public places, canvas flyers house-to-house, organize a “Get Out to Vote” campaign, make news clips for TV stations, watch opposition publicity and arrange for rebuttals, and place testimonial ads in local newspapers.Id.

Gerald Neely's A Critical Look: Montana's New Constitution was circulated in the months between the close of the 1972 Constitutional Convention and the vote to ratify. Neely outlined for Montana voters the changes brought about by the proposed constitution, and Section 4 was among the Bill of Rights provisions addressed. Presented to readers under the heading, "Discrimination," Section 4 was described as a provision that would put an end to discrimination perpetuated by the state, and by private citizens and organizations, going "far beyond current state or federal laws in the types of discrimination involved and with respect to who it applies to."Neely, Gerald J., The New Montana Constitution; A Critical Look, 1972.