II.21. Bail

“All persons shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, except for capital offenses, when the proof is evident or the presumption great."

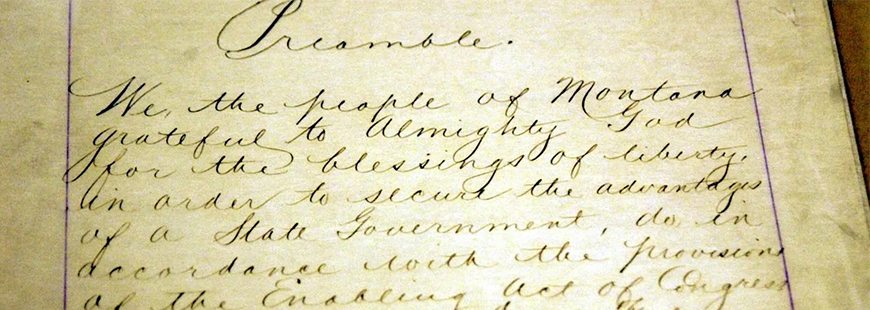

History

Sources

1884 Montana Constitution (proposed)

That all persons shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, except for capital offenses when the proof is evident or the presumption is great.

1889 Montana Constitution

All persons shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, except for capital offenses, when the proof is evident or the presumption great.

Drafting

Bill of Rights Committee Proposal (Comments)

The committee voted unanimously to retain this section unchanged. As it stands, the section announces that all persons are bailable except in certain capital offenses. No delegate proposals were received on this provision.Montana Const. Convention Committee Comments, 639-40 (Vol. II).

Montana Constitutional Convention Floor Debate

Delegate R.S. Hanson: The committee voted unanimously to retain this section unchanged. As it stands, the section announces that all persons are bailable except in certain capital offenses. No delegate proposals were received on this provision.5 Verbatim Transcript 1771 (Mar. 9, 1972).

Ratification

Delegate Hanson informed the other delegates that the committee unanimously voted to retain Section 21 unchanged and stated that no delegate proposals had been received on the provision. 5 Verbatim Transcript 1771 (Mar. 9, 1972). The Delegates adopted the committee proposal without opposition on March 9, 1972. Id. The delegates ultimately adopted the final draft of Section 21 unchanged on March 22, 1972.7 Verbatim Transcript 3001-02 (Mar. 22, 1972). 1972 Official Text with Explanation: “Identical to the 1889 constitution. Guarantees that all persons are bailable except in case of certain offenses punishable by death.

Interpretation

Mont. Code Ann. § 46-9-102 State ex rel. Murray v. Dist. Court, 35 Mont. 2504, 190 P. 513 (1907) This case came under a writ of supervisory control by the Silver Bow County Attorney, seeking review of the court’s decision to admit defendant to bail. Defendant Michael Daly was charged with deliberate homicide of Charles Kern in Butte, Montana. In the charging documents, there was no mention of bail. Daly orally petitioned the district court for an order allowing and setting bail. The district court granted the petition and admitted Daly to $10,000 bail. The county attorney, however, opposed Daly’s petition and resisted bail, stating that the proof of Daly’s guilt was evident, and the presumption of his guilt was great. The county attorney did not provide any testimony to substantiate his opposition. The Supreme Court held that the constitutional exception denying bail in capital offenses is not self-executing, and that the prosecuting attorney must make some showing of proof. “[W]hen an application is made for bail, in a capital case, the county attorney, if he resists the application, should make some showing that the proof is evident or the presumption great, thus bringing the case within the exception mentioned in the Constitution. On failure to make such showing, the defendant is entitled to bail in all cases[.]”35 Mont. at 507, 190 P. at 514. The Court stated, however, that if the attorney does make such a showing, “the court or judge should refuse bail without hesitation.”Id.

Miller v. Eleventh Judicial Dist. Court, 2007 MT 58, 336 Mont. 207, 154 P.3d 1186 Defendant Terry Miller was charged with negligent homicide after a drunk-driving incident. His bail was originally set at $30,000, but subsequently lowered to $10,000 after he informed the court he could not pay the original amount, though he made no actual showing of indigence at his bail hearing.2007 MT 58, ¶ 9. Miller argued that because he was indigent, any amount of bail would violate his constitutional right to bail under Article II, Section 21. Id. ¶ 2. The Court noted that Miller was correct in that he had a presumptive right to reasonable bail, but stated that Miller had a burden of presenting a record to prove that he had no ability to pay or that there were reasonable conditions he could have been released on which would ensure the protection of the community. Id. ¶ 15. See also Mont. Code Ann. §§ 46-9-106, 108, 111. Absent such proof, the Court held there was no violation of his constitutional right to bail.

Commentary

Montana Constitutional Convention Study

The Montana Constitution contains two provisions relating to bail. Article III, Section 20 provides: “Excessive bail shall not be required . . . .” This provision is identical with the federal Eighth Amendment. The Montana Constitution also goes beyond the explicit wording of the federal document in Article III, Section 19: “All persons shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, except for capital offenses, when the proof is evident or the presumption great.”

The rights reflected in those provisions have deep historical roots. The old English common law extended bail in all cases—partly because of the costs and difficulties in detention. Exceptions gradually were introduced until, by the mid-eighteenth century, bail was not allowed wherever an offence was of very substantial nature. This was at the time when there were in excess of 160 capital crimes; thus, offenses which were bailable were few and minor. In 1689, the English Bill of Rights announced the principle that bail must be reasonable; in this enactment, Parliament charged the ousted king with infringing the liberties of citizens by denying reasonable bail. There are very good reasons for allowing a person accused of a crime to be free on reasonable bail. As stated by Chief Justice Vinson in a 1951 Supreme Court case, “the traditional right to freedom permits the unhampered preparation of a defense.” Further, unless the right to bail before trial is preserved, the presumption of innocence, secured only after centuries of struggle, would lose its meaning.” Society may be entitled to assure that the accused will be present at his trial; however, if an accused is presumed innocent until convicted, he stands on the same footing as other citizens in society and does not belong in jail. Another rationale, state in an old Supreme Court case, is:

The statutes of the United States have been framed upon the theory that a person accused of crime shall not, until he has been finally adjudged guilty in the court of last resort, be absolutely compelled to undergo imprisonment or punishment, but may be admitted to bail, not only after arrest and before trial, but after conviction and pending a writ of error.

For these and other reasons, provisions on bail have found their way into nearly every constitutional list of procedural safeguards. The Montana constitutional provisions are supplemented by Title 95, Chapter 11 of the Revised Codes of Montana, 1947. Included in these statutes are provisions for the defendant’s release on his own recognizance, for overrriding[sic] the presumption of entitlement to bail, for bail after conviction (largely discretionary), for determining amount of bail and so on. Montana Constitutional Convention Study No. 10, Bill of Rights, 152-53 (1972) (footnotes omitted) (emphasis in original).