II.23. Detention

Article II, Section 23. Detention. No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same; if he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner provided by law, and in the presence of the accused and his counsel, or without their presence, if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof.

History

Sources

England

The Second Act of Phillip and Mary (1555). And be it further enacted, that the said Justices shall have Authority by this Act, to bind all such be Recognizance or Obligation, as do declare any Thing material to prove the said Manslaughter or Felony against such Prisoner as shall be so committed to Ward, to appear at the next general Gaol-delivery to be holden within the County, City or Town Corporate where the Trial of the Said Manslaughter or Felony shall be, then and there to give Evidence against the Party. Stacey M. Studnicki,Material Witness Detention: Justice Served or Denied?, 40 Wayne L. Rev. 1533, 1536, n.12 (1994) (quoting 2 & 3 Phil. & Mar., ch. 10).

Statute of Elizabeth (1562). If any person or persons upon whom any process out of any of the courts of record within this realm or Wales shall be served to testify or depose concerning any cause or matter depending in any of the same courts, and having tendered unto him or them, according to his or their countenance or calling, such reasonable sums of money for his or their costs or charges as having regard to the distance of the places is necessary to be allowed in that behalf, do not appear according to the tenor of the said process, having not a lawful and reasonable let or impediment to the contrary, that then the party making default shall forfeit £ 10 and give further recompense for the harm suffered by the party aggrieved. 5 Eliz. I, c. 9, 12 (1562).

Federal

Statutes

The First Judiciary Act of 1789. The Act provided for taking the deposition in a civil case of "any person...who shall live at a great distance from the place of trial than one hundred miles, or is bound on a voyage to sea, or is about to go out of the United States, or out of such district...or is ancient or very infirm." Studnick, supra note 1, at 1536 n. 21 (quoting 1 Stat. 23, 88). The Act provided that a person could be compelled to appear and be deposed, and if the witness could not be produced at trial, the deposition could be used as the witness's testimony. Studnick, supra note 1, at 1536, n. 20 (citing 1 Stat. at 89). The Act also allowed for the recognizance of witnesses for their appearance to testify in the case, and authorized imprisoning witnesses who failed to appear. Studnick, supra note 1, at 1536–37, n. 22 (citing 1 Stat. at 91).

Bail Reform Act of 1966. If it appears by affidavit that the testimony of a person is material in any criminal proceeding, and if it is shown that it may become impracticable to secure his presence by subpoena, a judicial officer shall impose conditions of release pursuant to section 3146. No material witness shall be detained because of inability to comply with any condition of release if the testimony of such witness can adequately be secured by deposition, and further detention is not necessary to prevent a failure of justice. Release may be delayed for a reasonable period of times. until the deposition of the witness can be taken pursuant to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. 18 U.S.C. § 3149.

United States Constitution

The federal constitution does not provide for any rights regarding detaining witnesses in criminal proceedings. See Dorwart v. Caraway, 2002 MT 240, ¶ 85; Buhmann v. State, 2008 MT 465, ¶ 158; Larry M. Elison and Fritz Snyder, The Montana State Constitution: A Reference Guide, 20 (2001).

Michigan

Statutes

Laws of the Territory of Michigan (1820). And be it further enacted, that every justice of the peace may issue subpoenas for witnesses being in the county in which the justice resides, or within fifteen miles of the place of trial; and every such witness who shall not appear, or appearing, shall refuse to give evidence in such action, shall forfeit and pay for every such default of refusal, (unless some reasonable cause be proved, on oath, to the satisfaction of the said court) such fine or fines, not exceeding the sum of ten dollars, nor less than sixty-two cents, as the said court shall think reasonable to impose; and the said court is hereby authorised and required to issue a warrant to any constable, to levy the same of the goods and chattels of the offender, and for want thereof, to take and convey him or her to the gaol of the county wherein the offence shall have been committed, there to remain until he or she shall pay such fine, together with the costs attending the same, or be discharged by due course of law. Act of May 20, 1820, Laws of the Territory of Michigan, § 8 at 230 (1820).

Revised Statutes of Michigan (1846). When the prisoner is admitted to bail, or committed by the magistrate, such magistrate shall bind by recognizance, the complainant, and all the material witnesses against such prisoner, to appear and testify at the next court having cognizance of the offence, and in which the prisoner shall be held to answer, and it shall be competent, in all cases contemplated in this section, for any magistrate in the county where any such offence is alleged to have been committed, to issue process to compel the attendance of any witness or witnesses, before him, at any time in vacation or between the terms of the court having cognizance of the offence, for the purpose of compelling such witnesses to enter into any recognizance required by the provisions of this section. If the magistrate shall be satisfied by due proof, that there is good cause to believe that any such witness will not perform the condition of his recognizance, unless other security be given, such magistrate may order the witness to enter into a recognizance, with one or more sureties as may be deemed necessary, for his appearance at court. When any married woman or minor is a material witness, any other person may be allowed to recognize for the appearance of such witness. All witnesses required to recognize, either with or without sureties, shall, if they refuse, be committed to prison by the magistrate, there to remain until they comply with such order, or be discharged according to law. Revised Statutes of Michigan, ch. 163, §§ 19-22 (1846).

1850 Michigan Constitution

Article VI, Section 31. Excessive bail shall not be required; excessive fines shall not be imposed; cruel or unusual punishment shall not be inflicted, nor shall witnesses be unreasonably detained.

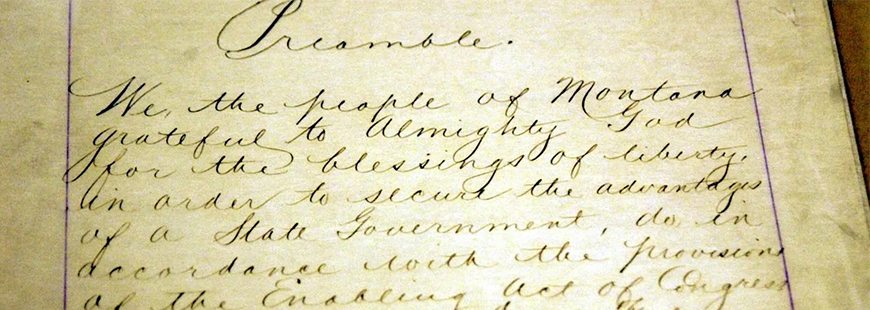

Montana

1884 Montana Constitution (proposed)

Article I, Section 17. That no person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any case longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security, he shall be discharged; if he can not give security, his deposition shall be taken by some Judge of the Supreme, district, or county for that purpose, of which time and place the accused and the attorney prosecuting for the people shall have reasonable notice. The accused shall have the right to appear in person and by counsel. If he have no counsel, the judge shall assign him one in the behalf only. On the completion of such examination, the witness shall be discharged on his own recognizance, entered into before said judge, but such deposition shall not be used, if in the opinion of the court the personal attendance of the witness might be procured by the prosecution, or is procedure by the accused. No exception shall be taken to such deposition as to matters of form.

1889 Montana Constitution

Article III, Section 17. No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same; if he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner prescribed by law, and in the presence of the accused and his counsel, or without their notice of the time and place thereof. Any deposition authorized by his section may be received as evidence on the trial, if the witness shall by dead or absent from the state.

Drafting

Committee Report

Bill of Rights Proposal Number 8

Article II, Section 23 is exactly the same as Article III, Section 17 of the 1889 Montana Constitution. The provision prohibits unreasonable detention of witnesses and prescribes in detail the procedure for securing testimony in the event the witness cannot be procured from the trial. No delegate proposals were received on this particular section. 5 Verbatim Transcript 1772 (Mar. 9, 1972), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

Transcript

Clerk Smith: “Section 23. Detention. No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same. If he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner prescribed by law and in the presence of the accused and his counsel or without their presence if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof. Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on the trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from the state.” Section 23, Mr. Chairman.

Delegate Foster: Mr. Chairman. I move that when this committee does rise and report, after having had under consideration Section 23 of the Bill of Rights Proposal Number 8, it recommends that the same be adopted. Mr. Chairman. This section is exactly the same as Article III, Section 17, in the present Constitution. The provision prohibits unreasonable detention of witnesses and prescribes in detail the procedure for securing testimony in the event the witness cannot be procured for the trial. No delegate proposals were received on this particular section. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Delegate Habedank: In connection with Section 23, Mr. Dahood, was any consideration given by your committee to enlarging the use of the deposition so that it could be used under circumstances where the witness was not absent from the state or dead? It occurs to me that there are many instances which would arise, where a deposition has been so taken, that the evidence is necessary, the witness cannot be located. He may be ill, many other things.

Delegate Dahood: Well, Mr. Well, Mr. Habedank, that was discussed to some extent, not any great extent; but we felt that the Montana Civil Procedure Act would take care of that under the discovery Sections, 26 through 37. And we thought that the deposition sections contained therein covered those situations that you refer to now.

Delegate Habedank: Did you consult with any prosecuting attorneys-I have never been one-as to whether or not they have ever

Delegate Dahood: Habedank, we did not consult with any prosecuting attorney. Again, we have the new Criminal Code which we think, in certain sections, covers that situation. And we did not see that there was any particular reason or need for any constitutional change. That is why we stayed with the section as it is.

Delegate Kelleher: I just Delivered a proposed amendment to the clerk, Mr. Chairman. It simply would strike the last sentence off and I move to strike the last sentence of Section 23, starting at lines 24 through 26 on page 8. Mr. Chairman.

Chairman Graybill: Explain you want to strike the last sentence?

Delegate Kelleher: Only the last sentence.

Chairman Graybill: The last sentence begins–

Delegate Kelleher: “Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on a trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from the state.”

Chairman Graybill: All right. Mr. Kelleher has proposed an amendment to Section 23 which would strike the last sentence from the language of Section 23: “Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on a trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from

Delegate Kelleher: The reason- the primary reason for striking this, Mr. Chair- man, is that I believe it clearly violates Section- Amendment 6-of the federal Constitution which, as you know, has been incorporated into Article XIV. The matter is well covered under Section 95.1802. In fact, I think the whole section is constitutional, but it is a rather important matter, so I did not move to strike the whole section. At page 171 of the Bill of Rights Committee’s own report–the very fine work done by Mr. Applegate–he points out the fact that in Pointer versus Texas, that was a 1965 case, the 6th Amendment was put in the 14th Amendment-and, of course, that was written many years after our own-original Constitution was drafted-that the government can- not use such a deposition. The deposition may be used by the defendant. And we could amend to put that-to allow that in the last sentence, but that’s already included in our statutes, so I see no need for it. And this is very similar to Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure; and in Moore’s Federal Practice, the commentary reads: “The government has no right to move to take a deposition under Rule 15. The use of depositions in criminal cases has always raised questions of possible infringement of a defendant’s 6th Amendment right to confront witnesses against him. This was no doubt the reason for the Supreme Court’s rejection of the original advisory commit- tee’s proposal to permit government depositions, as well as for the rejection of a similar provision contained in a proposed amendment.” Now, I realize, as I said, that it’s in the present Constitution, but that amendment-that portion of it was declared unconstitutional. If the committee wants to allow the defendant, as it is in the federal rule, to use these depositions, I have no objection to that, but just that-so long as the government in a prosecution cannot use the deposition because of the 6th Amendment. And that matter, incidentally, is very well covered in the committee’s following section, Section 24, the fourth line at the bottom of page 8, where we read: “to meet the witnesses against him face to face”. Even though the deposition has been taken, that-the criminal defendant still has a right to have that deponent- have the jury examine his demeanor on the wit- ness stand. Thank you.

Delegate Dahood: Mr. Chairman. We do not object to the motion by Delegate Kelleher, but I think I should explain some of the problems that have been discussed, for the benefit of the nonlawyer delegates. The word “deposition” simply means that you take the testimony of a witness, under oath before a court reporter, and then that testimony is transcribed. When you have a material witness who is absolutely essential to the case for the state or the prosecution, it sometimes becomes necessary to preserve that testimony for the benefit of the state by taking what is called a deposition. Again, nothing more nor less than the testimony of that witness, under oath, by question and answer. The Montana Criminal Code is going to protect the defendant, because that deposition can only be taken upon proper notice. And one of the bulwarks of liberty under our system of law is the right of the defendant to confront the witness who may stand against him and through his counsel to cross- examine that witness. That right is provided when a deposition is taken. In other words, the state is represented by the prosecuting attorney, the questions are asked of that particular witness. Those questions are written down by the court reporter, as well as the answers; and then the attorney on behalf of the defendant will ask questions and they are written down along with the answers. And any objections with respect to any questions that may be wrong are then decided by the judge at a later time. Since these matters are covered within our Montana Criminal Code and, with respect to any other matter that may relate to any civil procedure, also covered by theMontanaCivi1 Procedure Code, there is really no problem. The constitutional guarantees are going to be applied. We did not take that sentence out, because we were quite concerned about making sure that, wherever we could, we left the basic rights of the people in the same language in which they were framed in 1889, where the language was still correct and was still proper and was still reflective of society’s cur- rent needs to have these particular rights in the Bill of Rights. With that explanation, I again state that the Bill of Rights Committee has no objection to the amendment to delete as proposed by Delegate Kelleher. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Chairman Graybill: On line 21, it says-it says in line 20 that the deposition of such a witness must be taken in the presence of the accused or his counsel or without their presence if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof. And then, down in your next section-Section 2 4 - it says “to meet the witnesses against him face to face”. Assuming a situation where a criminal- where a person might be charged but not yet apprehended, would you expect this person to come in and appear for the deposition? And if you don’t really expect that, then how are you going to let him meet the witnesses face to face? In other words, I’m bothered by Mr. Kelleher’s point that in some cases, the defendant-it isn’t just a matter of notice like in a civil case. This defendant may have good reason not to appear, and yet he wouldn’t be able to meet his accuser face to face as you are requiring in the next section.

Delegate Dahood: In my judgment, Mr. Chairman. I think it is absolutely essential that the person against whom that deposition is to be sued does appear, under circumstances where he is before the court under process of court. I should think that in the situation that you have just stated, that the particular defendant is not yet under the control of the court by effective service of process, and therefore in my judgment, he would not be bound by any deposition taken under those circumstances.

Chairman Graybill: That may be; that doesn’t appear to me from lines 22 and 23.

Delegate Dahood: Well, that would be my opinion: that the only time that you can use a deposition is when there has been fair process, just process, due process with respect to the defendant. There’s some technical reason to that defendant. There’s some technical reason as to why he is not within the power and jurisdiction of the court because he has not been arrested and arraigned. Under those circumstances, I do not think that this particular type of deposition procedure can be effective against him. And that is our thinking and my thinking as Chairman of the committee. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Delegate McDonough: Mr. Dahood-granting power to a trial judge to allow this deposition to be entered if all the qualifications are met in the preceding section and if they are met down below; whereby if it is struck out, regardless of whether–what the 6th Amendment says, until it’s specifically ruled on by the court maybe it should be left in to allow the prosecution to be able to introduce such a deposition even though, at the time of the trial, the defendant does not have the right to, you know, to be able to be present and cross-examined.

Delegate Dahood: Well, Delegate McDonough, I think you raised a good point. I think that the Montana Criminal Code, which, of course, was recently passed and which recently became law in Montana, does cover the point. But I think you’re correct that this does provide a direction to the court that if these other conditions are met, then this particular deposition shall be admissible. But in my judgment, I do not think eliminating this particular section is going to change the status of criminal procedure in any respect. And perhaps, Mr. Chairman, as long as these questions are being raised and there is some doubt, perhaps then we should reject the amendment. I, from a standpoint of substance, do not think it’s going to affect our present state with respect to civil procedure in the criminal area at all. But if there is some question, then I think perhaps then, even though I have no personal objection on behalf of the committee to the amendment, it ought to be rejected. We looked at this section. I looked at it; the other lawyers looked at it. There were things that we could have done, perhaps to make the wording more clear, perhaps to add something; but we did think that there were other areas of the law which, of course, were enacted by the Legislature that covered the situation. There are basic constitutional protections with respect to a defendant that must be honored at all times. But in view of the questions that have been raised, and questions by lawyers, I would think under the circumstances then, perhaps I should not agree with Delegate Kelleher and per- haps the section should remain as it is. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Delegate Davis: Mr. President [Chairman]. I would feel compelled to resist the amendment. There’s a lot of truth in what’s been said about the fact that the federal may control, but this has been in the statutes-or in the Consti–interpreted the last time in 147 Montana–I don’t know what year that would be, but about ’65 or after that–and they held that this provision allowing for the taking of depositions does not violate Article III, Section 16, of the Montana Constitution, which provides for the right to confrontation and that this deposition taken under authority of this provision are admissible upon trial upon showing the witness is either dead or not within the jurisdiction. It’s extremely important in a case, and I think I maybe can give you an example that may be of some benefit. In a recent criminal action, we had a real notorious criminal who robbed an old man down by the river, tied him up and he was going to kill him. The witnesses to the thing were from out-of-state. We’re permitted to take their deposition and preserve it. The testimony is then preserved, and in some instances, you don’t have the defendant himself captured. You don’t even know who he is, maybe, until several years later, in some recent cases in Montana. The first part of this section permits you to take this man-material witness and hold him unless he makes bail or take his deposition. Well, the whole theory is not to hold the material witness. It’s the right of another person is ‘involved here now, is the right of a witness. He’s not going to be confined till trial. You can release him, but he takes his deposition, If the defendant is unknown or in flight, it’s not necessarily prejudicial; it may never be used. In the case that I’m referring to, the defendant jumped $15,000 bail and was apprehended 2 years later, hoping that the old man would die. His testimony would then be gone, the case is gone against him; or the other material witness would be gone, who had moved out of state in the construction business. So I would think that it would be a grave mistake to take away this. If the courts-if the federal courts are very jealously guarding all rights of defendants, the Supreme Court is very jealously guarding all rights of defendant, and I don’t think it would accomplish what you’re really seeking to do by just deleting the last portion of this. There needs to be a provision for taking of depositions of material witnesses in any criminal case, and I’m sure we want to preserve that. Thank you.

Delegate Kelleher: Mr. Chairman. I didn’t mean to instigate a great debate over such a minor technical matter. But in State versus Storm, our own Supreme Court held-and this is no place to conduct an education class on criminal procedure. I realize that, too-but our Supreme Court, in 1953, said it was error for the trial court to allow the testimony of a witness at the first trial to be read into evidence at the second trial. It was the right of the defendant to have the jury seen- observe the witness upon the witness stand. It was his right that the jury see how the witness acted upon direct- and cross-examination. It was his right to have the jury judge the credibility of the witness from his appearance and manner while on the witness stand. None of these rights could be had except and unless the witness met the defendant-"face to face”- in the presence of the jury during the course of the trial. This is awful clear law. I thought it was. I had a murder case last summer, and the only wit- ness was a prostitute. And they had to go find her, put her in jail, take her deposition, and she took off. The Federal Court in Pointer versus Texas- once again, the blue and white book done by Mr. Applegate-clearly sets forth that “The Supreme Court held that the right would be enforced against the state under the 14th Amendment according to the same standards to protect those personal rights against federal encroachment.“- close quote. There’s no doubt-by striking the last sentence, they could still take the deposition of any defendant. They could put this person in jail. And the reason I didn’t strike the whole section is, as I told Chairman Dahood the other day I had planned originally to do, is that I think there’s some merit to leaving the first part of the section in so that they just can’t take them, lock them up, take their deposition and then forget about them. They have to release them, but even that’s covered by the statute. The more I’m thinking about it, Chairman Dahood, I think maybe the whole sec tion ought to be stricken. It’s unnecessary in the Bill of Rights and it’s covered by the federal-I mean, it’s covered by our statutory law, in Title 95 of the Revised Codes. If we want to leave in an unconstitutional provision, that’s all right. I’m not going to make a big issue-there’s a lot of other matters that are a lot more important, Mr. Chairman, that we should be getting on to. 5 Verbatim Transcript 1771–76 (Mar. 9, 1972) (edited), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

Vote

The delegates voted unanimously to retain the former Article III, Section 17 unchanged. 5 Verbatim Transcript 1775–76 (Mar. 9, 1972), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol5.pdf.

Style and Drafting Report

Style and Drafting Report Number 8

The Style Drafting Report for Article II, Section 23 made only one change–it changed line 26 to read "provided by law" as a opposed to "prescribed by law" in order to be consistent:

No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same. If he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner provided by law and in the presence of the accused and his counsel or without their presence if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof. Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on the trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from the state. 7 Verbatim Transcript 2504–05 (Mar. 16, 1972) (emphasis added), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol7.pdf.

Transcript

Delegate Joyce: Yes, Mr. Chairman. I’m going to move at this time to suspend the rules.

Chairman Graybill: On 23?

Delegate Joyce: On Section 23. And if I am successful, I would propose to strike the last sentence, because as I understand it, the United States Supreme Court has held that a deposition may not be received as evidence at the trial if the witness is dead or absent from the state; and it just seems to me that we really shouldn’t pass some- thing that’s contrary to the federal Constitution.

Chairman Graybill: Very well, the Chair understands Mr. Joyce’s motion to be to suspend the rules to-so that we could reconsider Section 23. And he has also further said that if that happened, he would make a motion to reconsider and would be interested in the last sentence; but notice that the whole section will be open. Is there any discussion of the motion to suspend the rules? All in favor of suspending the rules on Section 23, say Aye.

Chairman Graybill: Does any delegate want to change is vote? Very well, 64 having voted in favor and 16 against, the motion to suspend the rules is adopted. Mr. Joyce, do you want to make a motion to reconsider?

Delegate Joyce: Mr. Chairman. I move to reconsider the section–the action of the Convention on Section 23, and if that motion passes I would have a motion to delete the last sentence.

Chairman Graybill: Is there discussion on the motion to reconsider? All in favor of the motion to reconsider, say Aye.

Chairman Graybill: It’s adopted. Now, Mr. Joyce, do you want to state your–Mr. Joyce, you did vote on the prevailing side when we adopted this, didn’t you? To the best of your recollection? (Laughter).

Delegate Joyce: Let me say I think so.

Chairman Graybill: Very well, what’s your motion?

Delegate Joyce: Mr. Chairman. I move to delete the last sentence of Section 23, on line 29, at page 13–that’s where I’m reading the following words, beginning with “Any”: “Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on the trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from the state.”

Chairman Graybill: Very well. You may have a motion deleting the last sentence beginning with the word “Any” in line 29: “Any deposition with the word “Any” in line 29: “Any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on the trial if the witness shall be dad or absent from the state.” Mr. Joyce.

Delegate Joyce: Mr. Chairman. It’s my-as I understand it, the United States Supreme Court has held that you cannot use a deposition in a criminal trial against a defendant in that, if the person-the witness is dead, he must-his evidence is gone forever. And if he’s absent from the state, you can’t use the deposition against him because the federal Constitution, which guarantees that a person will be confronted by-has the right to be confronted by his accusers-that on the trial of the case, the jury has the right to see the accuser to test his credibility and witness on the stand and if he isn’t there the evidence just can’t be admissible. And any constitution or statutes that authorize it violate the federal Constitution. And since the Supreme Court has so held, it seems to me that adopting a Constitution thereafter, that we really shouldn’t fly in the face of the United States Supreme Court.

Delegate Dahood: Mr. Chairman. There is some question as to whether or not this particular provision would conflict with that particular decision, because there are instances where the testimony that is so preserved may be in favor of defendant. But in any event, the Criminal Code of the State of Montana, which was recently enacted, does provide for the particular procedure involved in these matters. And because of that concern that’s been expressed by Delegate Joyce and several other lawyers who are members of the Convention, the committee would have no objection to deleting that sentence. It does not take away from the substance of that particular Section 23. 7 Verbatim Transcript 2504–06 (Mar. 16, 1972) (edited), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol7.pdf.

Vote

The delegates voted unanimously to delete "any deposition authorized by this section may be received as evidence on the trial if the witness shall be dead or absent from the state," from Article II, Section 23:

No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same; if he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner provided by law, and in the presence of the accused and his counsel, or without their presence, if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof. 7 Verbatim Transcript 2506 (Mar. 16, 1972), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol7.pdf.

Final Consideration

The committee voted 95 to 2 to delete the provision in 1889 constitution that depositions may be used in a trial if the witness who gave it is dead or absent from the state. The retained language is identical to the 1889 constitution. 7 Verbatim Transcript 2651–52 (Mar. 18, 1972), available at http://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/mt_cons_convention/vol7.pdf; The Proposed 1972 Constitution for the State of Montana Official Text with Explanation (Voter's Information Pamphlet) 7, available at http://www.umt.edu/law/library/files/1972voterspamphlet.

Ratification

1972 Voter's Pamphlet

General: Declaration of Rights

No rights protected by the present Montana Declaration of Rights are deleted or abridged in the proposed Constitution. These include the freedom of speech, assembly and religion; the right of self government; the right to acquire, possess and protect property; the right to suffrage; right to bail, and right to trial by jury, among others. In addition, the present Montana Provision guaranteeing the right to keep and bear arms is retained in total. The Proposed 1972 Constitution for the State of Montana Official Text with Explanation (Voter's Information Pamphlet) 3, available at http://www.umt.edu/law/library/files/1972voterspamphlet.

Article II, Section 23

Section 23. Detention. No person shall be imprisoned for the purpose of securing his testimony in any criminal proceeding longer than may be necessary in order to take his deposition. If he can give security for his appearance at the time of trial, he shall be discharged upon giving the same; if he cannot give security, his deposition shall be taken in the manner provided by law, and in the presence of the accused and his counsel, or without their presence, if they shall fail to attend the examination after reasonable notice of the time and place thereof. Mont. Const. art. II, § 23; The Proposed 1972 Constitution for the State of Montana Official Text with Explanation (Voter's Information Pamphlet) 7, available at http://www.umt.edu/law/library/files/1972voterspamphlet.

Article II, Section 23 Explanation

Deleted provision in 1889 constitution that depositions may be used in a trial if the witness who gave it is dead or out of state. Retained language is identical to 1889 constitution. The Proposed 1972 Constitution for the State of Montana Official Text with Explanation (Voter's Information Pamphlet) 7, available at http://www.umt.edu/law/library/files/1972voterspamphlet.

Vote

On June 6, 1972, Article II, Section 23 was ratified by the people of Montana as part of the Proposed 1972 Constitution.

Interpretation

1889 Montana Constitution, Article III, Section 17

State v. Vanella, 40 Mont. 326 (1910)

Following being convicted of second degree murder, Robert Vanella appealed the order denying him a new trial. Vanella argued that he deserved new trial because he was deprived of his right to meet the witnesses against him face to face, as the deposition of two witnesses was read into evidence. However, at the time of his trial, Vanella did not object to the depositions being used. Vanella, 40 Mont. at 336.

The Court first held that by failing to object to the depositions, Vanella waived his right to insist that showing of whether the witnesses were dead or absent from the state should have been made. Vanella, 40 Mont. at 337. Then the Court further explained what Article III, Section 17 required. The Court reasoned that, in criminal cases, that depositions must be taken on notice to and in the presence of the accused and his counsel, unless the accused and his counsel failed to attend the deposition. And that the burden is on the defendant to show that he was not present, or was not given an opportunity to be present, before he can complain. Vanella, 40 Mont. at 337–38.

In re Tooker, 147 Mont. 207 (1966)

Albert Tooker was charged by information for the murder of Harvey W. Dishaw. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 209, 212. Because the state’s material witnesses were transients, the county attorney decided to obtain their testimony via depositions as provided by Article III, Section 17 of the 1889 Constitution. Tooker received notice of the depositions of the two witnesses, and the depositions were taken by a court reporter with Tooker, his attorney, and the county attorney all present. Tooker’s attorney cross-examined both witnesses. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 212. On the trial date, neither witness could be found. As a result, each witness’s deposition was read to the jury. Ultimately, Tooker was found guilty of second degree murder, and was sentenced to forty years’ imprisonment. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 208, 213.

Tooker filed a petitioner for a writ of habeas corpus on May 25, 1965, raising several claims, including the Court recognized implied claim of infringement of Article III, Section 17. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 208, 215. Tooker alleges that the state made no sufficient showing that the witnesses were dead or absent from the state. The Court reasoned that the county attorney’s office, after the subpoenas they issued were returned without service, made real efforts to locate the two witnesses by contacting law enforcement agencies around the state and one agency out of the state. They were unable to find out the whereabouts of either witness. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 217. Accordingly, the Court found that there was a sufficient showing at the time of trial that the witnesses were absent from the state, denying Tooker’s habeas petition. Tooker, 147 Mont. at 220.

1972 Montana Constitution, Article II, Section 23

As of May 2018, there are no Montana Supreme Court cases interpreting Article II, Section 23 of the Montana Constitution. But see Buhmann v. State, 2008 MT 465, ¶ 158 (Nelson, J., dissenting) ("Certain causes of Article II, Section 23...provide guarantees to a greater extent than like provisions of the federal constitution."); Dorwart v. Caraway, 2002 MT 240, ¶ 85 (Nelson, J., concurring) ("Moreover, Montana's Constitution guarantees rights that are not provided for in the federal constitution...rights regarding the initiation of criminal proceedings, criminal detention, imprisonment for debt and rights of the convicted (Article II, Section 20, 23, 27 and 28 respectively."); Associated Press, Inc. v. Mont. Dep't of Revenue, 2000 MT 160, ¶ 61 (Nelson, J., concurring) ("Article II, Section 23 protects 'persons' from being imprisoned to secure testimony, except as specified.").

Commentary

Larry M. Elison and Fritz Snyder, The Montana State Constitution: A Reference Guide, 20 (2001).

Related Sources

Montana Constitution

Article II, Section 21. Bail. All persons shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, except for capital offenses, when the proof is evident or the presumption great.

Article II, Section 22. Excessive Sanctions. Excessive bail shall not be required, or excessive fines imposed, or cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Montana Code Annotated

Montana Code Annotated §§ 46-4-301–307 (2017). Investigative subpoenas -- reporting requirement for peace officers.

Montana Code Annotated §§ 46-15-101–120 (2017). Subpoenas and witnesses.

Montana Code Annotated §§ 46-15-201–204 (2017). Depositions.

Montana Code Annotated § 37-61-419 (2017). Attorney prohibited from becoming surety on bond.

Montana Code Annotated § 46-11-601 (2017). Recognizance by or deposition of witness.

Federal Statutes

18 U.S.C. § 3144 (2018). Release or detention of a material witness.

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure Rule 46. Custody; Supervising Detention.

State Statutes

Mich. Comp. Laws Serv. § 767.35 (2018). Witness; danger of loss of testimony; admission to bail or commitment.

Cases

Blair v. United States, 250 U.S. 273 (1919).

United States v. Anfield, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

Bacon v. United States, 449 F.2d 933 (9th Cir. 1971).

Hurtado v. United States, 539 F.2d 674 (9th Cir. 1976).

In re Cochran, 434 F. Supp. 1207 (D. Neb. 1977).

Arnsberg v. United States, 757 F.2d 971 (9th Cir. 1984), cert. denied, 475 U.S. 1010 (1986).

Ashcroft v. al-Kidd, 563 U.S. 731 (2011).

Secondary Sources

Stacey M. Studnicki, Material Witness Detention: Justice Served or Denied?, 40 Wayne L. Rev. 1533 (1994).

Ronald L. Carlson, Jailing the Innocent: The Plight of the Material Witness, 55 Iowa L. Rev. 1 (1969).

Ronald L. Carlson & Mark S. Voelpel, Material Witness and Material Injustice, 58 Wash. U. L. Q. 1, 2 (1980).

Catherine Cone, Text and Pretext: The Future of Material Witness Detention After Ashcroft v. al-Kidd, 62 Am. U. L. Rev. 333 (2012).