III.1. Separation of Powers

Mont. Const. Art. III, § 1

The power of the government of this state is divided into three distinct branches—legislative, executive, and judicial. No person or persons charged with the exercise of power properly belonging to one branch shall exercise any power properly belonging to either of the others, except as in this constitution expressly directed or permitted.

History

The doctrine of separation of powers is most often associated with social and political philosopher Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu’s work, Spirit of Laws.<cite> NCSL, Separation of Powers: An Overview, found at http://www.ncsl.org/research/about-state-legislatures/separation-of-powers-an-overview.aspx (last visited May 1, 2018).</cite> In it, Montesquieu uses the term “trias politica” to describe the division of governmental responsibilities into distinct branches, positing:

“When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty …. [T]here is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive.”<cite>Charles-Louis de Secondat Montesquieu, Spirit of Laws, Book XI, chapter 6 (1748). </cite>

Thus, under Montesquieu’s model, the political authority of the state ought to be divided into three branches of government to prevent the concentration of power into one branch, limit any one branch from exercising the core functions of another, and provide for checks and balances.<cite>NCSL, supra note 1. </cite> In short, separation of powers was an antidote to the perceived tyranny of monarchs such as King George III.<cite> See THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE para. 2 (U.S. 1776); M.J.C. VILE, CONSTITUTIONALISM AND THE SEPARATION OF POWERS 175-76 (2d ed. 1998) (The English theory of mixed government held that the presence in the legislature of the three states of monarchy, aristocracy, and people would prevent the constitution from degenerating into the corrupt forms of tyranny, oligarchy, or anarchy.).</cite>

As applied to the British constitutional system, Montesquieu discerned a separation of powers among the monarch, Parliament, and the courts of law.<cite>3 Modern Constitutional Law § 37:1 (3rd ed.). </cite> In the American colonies, however, distrust of the monarchy translated into distrust of colonial governors and, in turn, executives of state.<cite>Louis J. Sirico, Jr., “How the Separation of Powers Doctrine Shape the Executive,” Working Paper Series: Vill. U. Charles Widger Sch. L. at 3 (2008), found at http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/wps/art118 (last visited May 1, 2018). </cite> This distrust led to a debate among both state and federal constitutional drafters who sought to minimize executive power in trade for legislative omnipotence.<cite>Id. (quoting James Madison, Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, at 312 (W.W. Norton 1987). </cite> Debates abounded, with states such as New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire giving comparatively more power to the executive than their distrustful counterparts.<cite>Id. at 15-17. </cite> At the federal level, James Madison defended the Constitution’s adherence to the principles of Montesquieu in Federalist Papers numbers 47 and 48, and described the separation of powers as “essential to a free government.”<cite>James Madison, The Federalist No. 48 at 308 (New American Library ed., 1861). </cite> Madison felt that consolidation of power into just one branch of government, or “in the same hands,” was tantamount to tyranny.<cite>James Madison, The Federalist No. 47 at 373-74 (Hamilton ed. 1880) (quoted in United States v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437, 469 (1965). </cite>

Even a century later, Montana was no exception to the distrust of government in general, yet adopted separation of powers in each of its constitutional iterations just as Madison argued. Montana’s provision for three branches of government contained “many specific prohibitions, grants and mandates … all of which serve to limit legislative power.”<cite>Id. </cite> The same could be said of the powers of other branches of government.<cite>Larry Elison & Friz Snyder, The Montana State Constitution 4, 17-18 (Greenwood 2001). </cite>

Sources

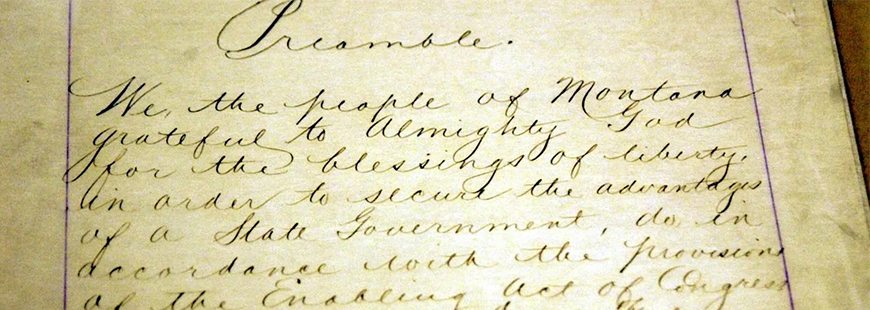

Separation of powers has been a cornerstone to Montana’s constitutional history from its nascent territorial formation to its modern 1972 form. In each constitution between then and now, separation of powers can be found in each source document, and in each the doctrine is evidently reformed and perfected until the 1889 constitution, which the 1972 constitution took verbatim:

Organic Act of the Territory of Montana, May 26, 1864 (13 Stat. 85)

- § 2 vests executive power and authority in the governor;

- § 4 vests legislative power and authority in the governor and legislative assembly, consisting of a council (7 members) and house of reps (13 members);

- § 6 extends powers of legislature to be consistent with U.S. Const., placing limits on legislative powers; requires presentment of bills to executive for approval or veto

- § 9 vests judicial power in one Supreme Court, district courts, probate courts, and justices of the peace

- § 15 gives governor power to define judicial districts and assign judges until legislative assembly thereafter exerts power in its first or subsequent sessions to organize, alter, or modify judicial districts and assign judges

Montana Territory Organic Act, March 2, 1867

(a.k.a. An Act amendatory of “An Act to provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Montana,” approved May 26, 1864; 14 Stat. 426)

- §§ 2, 3, 4 authorizes judiciary to hear and determine civil and criminal cases; limits on power; salaries; define judicial districts and assign judges

- § 5 clarifies the governor’s duties in regards to elections

- §§ 5, 6 revives the lapsed legislative functions of the Territory; authorizes the creation of legislative districts for the election of representatives to “both houses of the legislative assembly” and nullifies all prior laws of the “so-called legislative assembly of 1866”

Montana Constitution, 1884: Art III, § 1

“The powers of the government of this State are divided into three distinct departments: The Legislative, Executive, and Judicial; and no person, or collection of persons, charged with the exercise of powers properly belonging to one of these departments, shall exercise any powers properly belonging to either of the others, except as in this Constitution expressly directed or permitted.”

Provisions enumerating department powers:

- Art. IV Legislative Department

- Art. V Executive Department

- Art. VI Judicial Department

Enabling Act of 1889 (25 Stat. 676)

The Enabling Act of 1889 omits any specific reference to separation of powers between branches of government, but implications abound if only by reference to branches by name.

- § 3 authorizes vote for the legislative assembly

- § 4 commands the state to adopt the United States Constitution; authorizes the creation of state constitution so long as it is “republican in form”

- §§ 5, 21 refer to judicial and legislative districts

- § 12 provides for public lands to be granted to the state upon admission into the Union “for the purpose of erecting public buildings at the capital of said States for legislative, executive and judicial purposes.” (Emphasis added).

Comparison to Article IV of the 1889 Montana Constitution

COMMENT: With little debate and no changes, this Article was adopted from Article III of the 1884 Constitution (Proceedings, p. 691). This section has never been amended, nor have any amendments been proposed to alter its 1889 wording.<cite>Mont. Const. Conv. Comm., “Comparison of the Montana Constitution with the Constitutions of Selected Other States,” Montana Constitutional Convention Occasional Papers: Report No. 5, art. IV at 1 (1971-1972). </cite>

“Article four. Distribution of Powers, is the same as Colo.”<cite>Mont. Const. Conv. Comm., Elbert F. Allen, “Sources of the Montana State Constitution,” Montana Constitutional Memorandums: Memorandum No. 4 at 3 (June 10, 1910).</cite>

Legislative Council Report on the Montana Constitution

Summary:

The constitutions of forty states explicitly refer to the three branches of government; ten state constitutions and the federal constitution have no specific provision for separation of powers. Of the six constitutions used for comparative purposes, only two (Michigan and New Jersey) have a similar provision. Although a power of government may be vested in more than one branch in modern times, this article clearly expresses the basic concept of separation of powers and removal might imply rejection of that concept. Substitution of the term “branches” for the term “departments” would be more accurate, but the Council concludes that this article is adequate at the present time.<cite>Mont. Const. Conv. Comm., “Legislative Council Report on the Montana Constitution,” Montana Constitutional Convention Occasional Papers: Report No. 6 at 17 (1971-1972). </cite>

Comparison to U.S. Constitution

Where the Montana Constitution specifically provides for the separation of powers, the U.S. Constitution only implies it through its enumerated powers to the legislature, executive and judiciary:

The doctrine of separation of powers is fundamental in our system. It arises, however, not from Art. III nor any other single provision of the Constitution, but because ‘[b]ehind the words of the constitutional provisions are postulates which limit and control.’<cite> National Mut. Ins. Co. of Dist. of Col. v. Tidewater Transfer Co., 337 U.S. 582, 590–91 (1949) (quoting Principality of Monaco v. Mississippi, 292 U.S. 313, 322 (1934)).</cite>

To wit:

- Art. I, § 1: All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

- Art. II., § 1, cl. 1: The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.

- Art. III, § 1: The judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.

Drafting

Little discussion was had over whether separation of powers ought to be revised in the 1971-1972 constitutional convention (as noted in Comparison of Article IV of the Montana Constitution, supra). However, in Montana’s Constitutional Convention Study No. 12, author Richard F. Bechtel writes:

"Montana’s 1889 Constitution was written during a period in which legislatures were distrusted; as a result, it and other constitutions written during the same era are said to offer strong evidence of the belief that state officials cannot be trusted."<cite> Mont. Const. Conv. Comm., Richard F. Bechtel, “The Legislature,” Montana Constitutional Convention Studies at 1 (1971-1972). </cite>

Such distrust in 1889 may or may not have existed in 1972, but given the constitutional convention’s ready adoption of the 1889 text, such distrust lives on by its adoption.

Federal

The doctrine of separation of powers is not clearly stated in the constitution but flows naturally from the division of federal government into three branches, each given enumerated powers. Kwai Chiu Yuen v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 406 F.2d 499 (9th Cir. 1969), certiorari denied 395 U.S. 908.

Separation of powers was not instituted with the idea that it would promote governmental efficiency, but was looked to as a bulwark against tyranny. U.S. v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437, 443 (1965).

Violation of the doctrine of separation of powers occurs when there is an assumption by one branch of powers that are central or essential to the operation of a coordinate branch, provided that the assumption disrupts the coordinate branch in the performance of its duties and is unnecessary to implement a legitimate policy of the government. Chadha v. INS, 634 F.2d 408 (9th Cir., 1980), certiorari granted 454 U.S. 812, affirmed 462 U.S. 919.

The doctrine of separated powers is implemented by a number of constitutional provisions, some of which entrust certain jobs exclusively to certain branches, while others say that a given task is not to be performed by a given branch. For example, Article III's grant of ‘the judicial Power of the United States’ to federal courts has been interpreted both as a grant of exclusive authority over certain areas, Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 2 L.Ed. 60, and as a limitation upon the judiciary, a declaration that certain tasks are not to be performed by courts, e.g., Muskrat v. United States, 219 U.S. 346; cf. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579.

State

Judicial interference on the Executive Branch

Because of the division of governmental powers into three distinct departments under the Constitution, neither the district courts nor the Supreme Court may substitute their discretion for the discretion reposed in boards and commissions by legislative acts. Peterson v. Livestock Commission, 120 Mont. 140, 181 P.2d 152 (1947).

Chief water judge’s issuance of orders restraining and prohibiting Board of Natural Resources and Conservation and Department of Natural Resources and Conservation from adopting administrative rules in examination and determination of water rights was not an improper intrusion by the judiciary on executive powers, where the only effect of the orders was to require Board and Department to desist from making rules beyond their power. In re Dep’t of Nat. Res. & Cons., 226 Mont. 221, 740 P.2d 1096 (1987).

Judicial interference on the Legislative Branch

It is not function of courts to second-guess and substitute their judgment at every turn of the road for the judgment of the legislature in matters of legislation, and same is true in case of direct legislation by the people via the initiative process. State Bar of Mont. v. Krivec, 193 Mont. 477, 632 P.2d 707 (1981).

Generally, courts will acquiesce in legislative decision unless it is clearly erroneous, arbitrary or wholly unwarranted. Harvey v. Blewett, 151 Mont. 427, 443 P.2d 902 (1968).

Change in law is for the Legislature not the courts, and the courts should not add to, subtract from or amplify the terms of a statute. Fergus Motor Co. v. Sorenson, 73 Mont. 122, 235 P. 422 (1925); State v. Walker, 64 Mont. 215, 210 P. 90 (1922); State v. Board of Comm’rs of Hill Cnty., 56 Mont. 355, 185 P. 147 (1919).

Legislative interference on the Judicial Branch

The legislature cannot restrict or impair exclusive power of Supreme Court to regulate practice of law. Kradolfer v. Smith, 246 Mont. 210, 805 P.2d 1266 (1990).

The legislature may constitutionally delegate its legislative functions to an administrative agency, but it must provide, with reasonable clarity, limitations upon the agency’s discretion and provide the agency with policy guidance. In re Petition to Transfer Territory from High School Dist. No. 6, Lame Deer, Rosebud County, to High School Dist. No. 1, Hardin, Big Horn County, 15 P.3d 447, 303 Mont. 204 (2000).

Even though it is not the function of the court to interpret law based on what may be morally acceptable or unacceptable to society at any given time, and it is not judiciary’s prerogative to condone or condemn a particular lifestyle and behaviors associated with it on the basis of moral belief, simply because legislature has enacted law that may be a moral choice of the majority, courts do not have to simply acquiesce, and do have an obligation to scrupulously support, protect and defend the rights and liberties guaranteed to all persons under the Constitution. Gryczan v. State, 283 Mont. 433, 942 P.2d 112 (1997).

Under the separation-of-powers clause, the question of when cases shall be decided and manner in which they shall be decided is a matter solely for the judicial branches of government; statutes providing for forfeiture of one month’s pay of a judge if a decision is not reached or opinion written within 90 days of submission violates the separation-of-powers clause, notwithstanding that order directing State Auditor to forfeit one month’s pay was to be issued by the Supreme Court. Coate v. Omholt, 203 Mont. 488, 662 P.2d 591 (1983).

Legislative interference on the Executive Branch

Referendum that proposed a vote in the general election on whether to provide a tax credit and potential tax refund, or outright State payment, to individuals in years in which there is a certain level of projected surplus revenue violated the state constitutional separation of powers provision; independent judgment and evaluation with respect to the numerous estimates and projections of the State budget were functions plainly entailing execution of the law and were thus consistent with executive branch functions that were routinely required to implement legislative enactments. MEA-MFT v. McCulloch, 291 P.3d 1075, 366 Mont. 266 (2012).

When delegating legislative authority to a private party, the Legislature cannot ignore the limitations required of it when delegating to an administrative agency. Legislature may constitutionally delegate its legislative functions to an administrative agency, but it must provide, with reasonable clarity, limitations upon the agency’s discretion and provide the agency with policy guidance. State v. Mathis, 68 P.3d 756, 315 Mont. 378 (2003).

Doctrine of separation of powers is not violated where governor exercises the very sorts of powers and duties authorized by legislature in the statutes it enacted. Montana Public Employee’s Ass'n v. Office of Governor, 271 Mont. 450, 898 P.2d 675 (1995).

There is nothing improper, constitutionally or otherwise, in the legislature making its authorizations contingent upon administrative decisions properly made in the executive side of the state government. Grossman v. State, Dept. of Nat. Res., 209 Mont. 427, 682 P.2d 1319 (1984).

Executive interference (ultra vires) on the Legislative Branch

A statute granting legislative power to an administrative agency will be held to be invalid if the legislature has failed to prescribe a policy, standard, or rule to guide the exercise of the delegated authority; if the legislature fails to prescribe with reasonable clarity the limits of power delegated to an administrative agency, or if those limits are too broad, the statute is invalid. In re Petition to Transfer Territory from High School Dist. No. 6, Lame Deer, Rosebud County, to High School Dist. No. 1, Hardin, Big Horn County, 15 P.3d 447, 303 Mont. 204 (2000).

Attorney General could not exercise legislature’s subpoena power. State ex rel. Woodahl v. Dist. Ct. of 1st Judicial Dist.,Lewis & Clark Cnty., 166 Mont. 31, 530 P.2d 780 (1975).

The public policy of the state is for the law-making power of the state to declare, and the state has no public policy except that which is found in its Constitution and laws made by the law-making power, not by administrative officers acting solely on their own ideas of public policy in promulgating regulations. State ex rel. McCarten v. Corwin, 119 Mont. 520, 177 P.2d 189 (1947).

Executive interference on the Judicial Branch

Only the sentencing judge has the power to impose probation conditions that affect a defendant’s rights, and without statutory authority to do so, the Department of Corrections cannot add conditions to those articulated in a district court’s judgment. State v. Gillingham, 176 P.3d 1075, 341 Mont. 325 (2008).