III.4. Initiative

History

Sources

1884 Montana Constitution (proposed)

There was no power of initiative reserved to the people in the proposed 1884 Constitution. The legislative power vested solely in the Legislative Assembly of the State of Montana.1884 Mont. Const. art IV, § 1 (proposed).

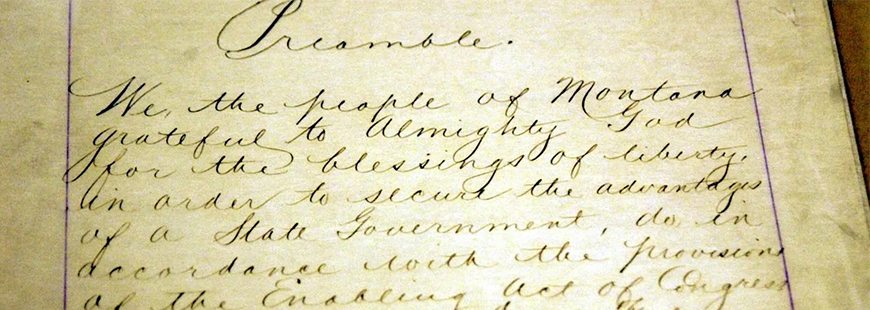

1889 Montana Constitution

There was no power of initiative reserved to the people in the original 1889 Constitution. As in the proposed 1884 Constitution, the legislative power vested solely in the Legislative Assembly of the State of Montana.1889 Mont. Const. art V, § 1. In 1905, however, the Ninth Legislative Assembly submitted an amendment to Article V, Section 1, to the voters of Montana. 1905 Mont. Laws 139-141. The voters approved the amendment, which became effective December 7, 1906. Mont. Legis. Council Rept. on the Mont. Const. 6, 41st Legis., 21 (Oct. 1968). As amended, Article V, Section 1, provided:

The Legislative Authority of the State shall be vested in a Legislative Assembly, consisting of a Senate and House of Representatives; but the people reserve to themselves power to propose laws, and to enact or reject the same at the polls, except as to laws relating to appropriations of money, and except as to laws for the submission of constitutional amendments, and except as to local or special laws, as enumerated in Article V, Section 26, of this Constitution, independent of the Legislative Assembly; and also reserve power at their own option, to approve or reject at the polls, any Act of the Legislative Assembly, except as to laws necessary for the immediate preservation of the Public peace, health or safety, and except as to laws relating to appropriations of money, and except as to laws for the submission of constitutional amendments, and except as to local or special laws, as enumerated in Article V, Section 26, of this Constitution. The first power reserved by the people is the Initiative and eight per cent of the legal voters of the State shall be required to propose any measure by petition; provided, that two-fifths of the whole number of the Counties of the State must each furnish as signers of said petition eight per cent of the legal voters in such county, and every such petition shall include the full text of the measure so proposed. Initiative petitions shall be filed with the Secretary of State, not less than four months before the election at which they are to be voted upon.1905 Mont. Laws 139-140.

Other Sources

In 2001, the 57th Legislature passed SB 397, Increase Voter Participation in Statutory Initiative Process.2001 Mont. Laws Ch. 330 SB 397 referred the Montana Distribution Requirements for Statutory Initiatives Amendment (C-38) to the people.2002 Mont. Laws Balt. Meas. 38. C-38 amended clause 2 of Article III, Section 4 to read:

(2) Initiative petitions must contain the full text of the proposed measure, shall be signed by at least five percent of the qualified electors in each of at least

one-thirdone–half of thelegislative representative districtscounties and the total number of signers must be at least five percent of the total qualified electors of the state. Petitions shall be filed with the secretary of state at least three months prior to the election at which the measure will be voted upon.2002 Mont. Laws Balt. Meas. 38.

Supporters of C-38 argued that "by requiring signatures from half the counties we will ensure that a proposed initiative law has broad appeal and that people from varying geographic regions and economic bases agree that the idea merits debate and placement on the ballot."Mont. Sec. of State, 2002 Voter Information Pamphlet, 21. Opponents of C-38 argued it was an "unfair proposal that would use legal technicalities to make it harder for you to control your own government."Mont. Sec. of State, 2002 Voter Information Pamphlet, 22. On November 5, 2002, the people of Montana approved C-38.2002 Mont. Laws Balt. Meas. 38.

Drafting

Delegate Proposal No. 129 (Delegate Harlow): Delegate Harlow's proposal to amend Article V, Section 1, of the 1889 Constitution was referred to the General Government and Constitutional Amendment Committee.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 3, 1972, Vol. I at 257-258. The proposal, which was offered to provide for the recall of elected officials, included much of the same language regarding the initiative power as Article V, Section 1, of the 1889 Constitution. The proposal provided in part:

The people reserve to themselves power to propose laws, and to enact or reject the same at the polls, except as to laws relating to appropriations of money, and except as to laws for the submission of constitutional amendments, and except as to local or special laws, independent of the legislative assembly; and also reserve power, at their own option, to approve or reject at the polls, any act of the legislative assembly, except as to laws necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety, and except as to laws relating to appropriations of money, and except as to laws for the submission of constitutional amendments, and except as to local or special laws, the people also reserve to themselves the power to remove elected officials from office. The first power reserve by the people is the initiative and eight percent of the legal voters of the state shall be required to propose any measure by petition; provided, that two-fifths of the whole number of the legislative districts of the state must each furnish as signers of said petition eight percent of the legal voters in such district, and every such petition shall include the full text of the measure so proposed. Initiative petitions shall be filed with the secretary of state, not less than four months before the election at which they are to be voted upon.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 3, 1972, Vol. I at 257-258.

Delegate Proposal No. 140 (Delegate Bates): Delegate Bates included the initiative power in a new legislative article referred to the Legislative Committee.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 4, 1972, Vol. I at 274. Proposed Section 11. Referendum and Recall, provided in part:

The people may propose and enact laws by the initiative, including constitutional amendments and approve or reject acts of the legislature by referendum. (1) Initiative petitions must be signed by eight percent (8%) or more of the legal voters in each of the one-fourth (1/4) or more of the legislative districts and the total number of signers but me eight percent (8%) or more of the (total legal) voters of the state. Each petition must contain the full text of the proposed measure and shall be confined to one subject. Petitions must be filed with the secretary of state three (3) months or more prior to the election at which they will be voted upon.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 4, 1972, Vol. I at 277.

General Government Committee Majority Proposal Number 12: "The people may enact laws by initiative on all matters except appropriations of money and local or special laws prohibited by this Constitution. Initiative petitions must be signed by eight percent or more of the legal voters in each of one-third or more of the legislative representative districts and the total number of signers must be eight percent or more of the total legal voters of the state. Each petition must contain the full text of the proposed measure. Petitions must be filed with the Secretary of State four months or more prior to the election at which they will be voted upon. The enacting clause of all initiative measures shall be: 'Be it enacted by the people of the State of Montana.'"1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 19, 1972, Vol. II at 815-816.

General Government Committee Majority Proposal Number 12 Comments: "This is the provision for statutory initiative agreed on by the General Government and Legislative Committees. The General Government Committee feels the petition requirements of eight percent (8%) in each of 1/3 or more of the legislative representative districts and eight percent (8%) or more of the total legal voters of the state are high enough to prevent frivolous legislative efforts by a small minority, yet low enough to allow serious, popular measures to be initiated by the people."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Feb. 19, 1972, Vol. II at 819-820.

General Government Committee Proposal Number 12 Amendment, Debate, and Adoption: Before the Committee of the Whole considered the General Government Committee's proposal on Article III, Section 4, the General Government Committee offered a number of amendments to the Section.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2689. Chairman Graybill read the first amendment at the request of Delegate Etchart: "After the word 'constitution,' put in an asterisk, because we need to add a sentence, which can go at the top or bottom of the page. The sentence is: 'The highway revenue provided for in Article blank, Section 6, shall nevertheless be subject to appropriation by initiative.'"1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2689. The General Government Committee also amended its Majority Proposal by changing the signature petition requirements from eight percent to five percent of legal voters. 1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2689. Clerk Hanson then read Section 4 as amended and debate began on the proposal.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2695-2696.

Delegate Loendorf first offered an amendment to strike the following language from Section 4: "The enacting clause of all initiative measures shall be: Be it enacted by the people of the State of Montana."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2696. Delegate Loendorf viewed the language as non-substantive and argued that the language "may prevent laws being declared void on a technical basis."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2696. Delegate Brown stated that the General Government Committee was in favor of the amendment and it passed unanimously on a voice vote.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2696-2697.

Delegate Mahoney then proposed an amendment to change the time limit for filing petitions with the Secretary of State from four months to two months prior to the election.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2697. Delegate Kelleher spoke in favor of the amendment and Delegates Habedank, Vermillion, and Choate spoke against the amendment.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2697-2698. The amendment failed on a voice vote.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2698.

Delegate Joyce then offered an amendment to add the following sentence to the end of the Section: "The sufficiency of the initiative petitions shall not be questioned once the election is held."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2698. Delegate Joyce previously worked on a case in which an initiative's opponents challenged the sufficiency of the petitions after the initiative had been overwhelmingly approved by the voters.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2698. Delegate Joyce argued that once the voters approved an initiative, the sufficiency of the petitions became an unnecessary technical way to attack the will of the people.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2698-2699. Delegate Toole spoke in favor of the amendment and the Delegates adopted it on a voice vote. 1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2699.

Delegate Foster next offered an amendment to change the time limit for filing petitions with the Secretary of State from four months to three months prior to the election.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2699. Delegate Robinson and Delegate Etchart had a back and forth discussion on the reasoning behind the four month time limit and the amendment was eventually put to a roll call vote.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2699-2700. The amendment passed 63 to 29.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2701.

Delegate Harper offered an amendment to strike the following language from Section 4: "The highway revenue provided for in Article blank, Section 6, shall nevertheless be subject to appropriation by initiative."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2701. That language had just been added by an amendment from the General Government Committee before debate began on Article III, Section 4.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2689. Delegate Harper made two points regarding his concerns with the language: (1) it would create an exception to the general prohibition of appropriations of money by initiative; and (2) it would allow the people to amend the Constitution (Article blank, Section 6) with only five percent of the people signing the petitions instead of the ten percent required for Constitutional amendments.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2701. Delegate Habedank pointed out that the language simply eliminated a conflict between Article III, Section 4, and Article blank, Section 6, which allowed highway revenue to be "appropriated by a three-fifths vote of the members of each house of the Legislature or by initiated measure approved by a majority of the qualified electors."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2701-2702. A lengthy discussion ensued regarding the purposes and impact of the language in both Article III, Section 4, and Article blank, Section 6.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2702-2705. The Committee of the Whole went into recess so the General Government Committee and the Revenue and Finance Committee could meet to discuss the issue in greater depth.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2705-2706. Following the recess, a lengthy discussion between the Delegates again ensued about how to harmonize the two sections.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2706-2717. The amendment was finally put to a voice vote and the language was deleted.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2717. Article blank, Section 6, was also eventually amended to remove the language allowing highway revenue to be appropriated by initiative.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2789.

No other amendments were offered and the General Government Committee Proposal on Article III, Section 4, was adopted as amended by the Committee of the Whole.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 18, 1972, Vol. VII at 2717.

Style and Drafting Committee Report Number 12: (1) The people may enact laws by initiative on all matters except appropriations of money and local or special laws prohibited by this Constitution.

(2) Each initiative petition must contain the full text of the proposal. Each shall be signed by at least five percent of the qualified electors in each of at least one-third of the legislative representative districts and the total number of signers must be at least five percent of the total qualified electors of the state. A petition shall be filed with the secretary of state at least three months prior to the election at which it will be voted upon.

(3) The sufficiency of the initiative shall not be questioned after the election is held.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. II at 1019-1020.

Style and Drafting Committee Report Number 12 Amendment, Debate, and Adoption: The Committee of the Whole considered the Style and Drafting Committee Report on Article III, Section 4.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2820-2825. Delegate Schlitz first moved to adopt Article III, Section 4, subsection 1.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2820-2821. Delegate Brown moved to strike "prohibited by this Constitution" from the subsection.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2821. Delegate Brown considered this a style change and explained that Article V, Section 26, of the 1889 Constitution enumerated "all the local or special laws that cannot be enacted by initiative or by the Legislative Department."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2821. The Delegates thought a similar list would be provided elsewhere in the 1972 Constitution, but it was not.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2821. The amendment was passed on a voice vote and subsection 1 as amended was adopted.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2821-2822. Article III, Section 4, subsection 2, was adopted by the Committee of the Whole on a voice vote with no discussion.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2822. Article III, Section 4, subsection 3, was also adopted by the Committee of the Whole on a voice vote with no discussion.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2822.

During discussion of the Style and Drafting Committee Report on Article III, Section 5, Delegate Habedank pointed out that the language as drafted in Section 4, subsection 2, was inadequate because it required each petition to "be signed by at least 5 percent or more of the qualified electors."1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2823. After a motion passed to reconsider Section 4, subsection 2, Delegates Schlitz and Habedank each offered a number of amendments altering the language, so that subsection 2 would be amended to read as follows:

(2) Each iInitiative petitions must contain the full text of the proposal.ed measure, Each shall be signed by at least five percent of the qualified electors in each of at least one-third of the legislative representative districts and the total number of signers must be at least five percent of the total qualified electors of the state. A pPetitions shall be filed with the secretary of state at least three months prior to the election at which it the measure will be voted upon.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2823-2824.

The language of Section 4, subsection 2, was adopted as amended and Section 4, subsection 2, was adopted as amended by the Committee of the Whole.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2824-2825.

Final Consideration:The Delegates adopted the final draft of Article III, Section 4, 91-0 (9 absent) on March 20, 1972.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 20, 1972, Vol. VII at 2847.

Language as Adopted: Section 4. INITIATIVE. (1) The people may enact laws by initiative on all matters except appropriations of money and local or special laws.

(2) Initiative petitions must contain the full text of the proposed measure, shall be signed by at least five percent of the qualified electors in each of at least one-third of the legislative representative districts and the total number of signers must be at least five percent of the total qualified electors of the state. Petitions shall be filed with the secretary of state at least three months prior to the election at which the measure will be voted upon.

(3) The sufficiency of the initiative petition shall not be questioned after the election is held.1972 Mont. Const. Conv. Tr., Mar. 22, 1972, Vol. II at 1090.

Ratification

1972 Official Text with Explanation: "Revises 1889 constitution by requiring a petition to be signed by 5% of electors in 1/3 of the legislative districts instead of 8% in 2/5 of the counties."1972 Official Text with Explanation, 8.

A Missoulian article covered the General Government Committee report in March, 1972.Dennis E. Curran, Con-Con to Debate Gambling, The Missoulian (March 17, 1972). It stated that the report "includes provisions aimed at giving the people more say in their state government—initiative, referendum, and recall."Dennis E. Curran, Con-Con to Debate Gambling, The Missoulian (March 17, 1972). The article went on to state that "initiative allows the voters to enact legislation."Dennis E. Curran, Con-Con to Debate Gambling, The Missoulian (March 17, 1972). It pointed out that the 1889 Constitution included the initiative power, but the Committee had made the initiative power "more workable" in the 1972 Constitution.Dennis E. Curran, Con-Con to Debate Gambling, The Missoulian (March 17, 1972).

Interpretation

A United States District Court found the county distribution requirements in Article III, Section 4, clause 2, unconstitutional.Mont. Pub. Interest Group v. Johnson, 361 F.Supp.2d 1222 (D. Mont. 2005). The court held that requiring signatures from five percent of qualified voters in at least half of the counties violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.Mont. Pub. Interest Group v. Johnson, 361 F.Supp.2d 1222, 1230 (D. Mont. 2005). The court permanently enjoined the State from enforcing those provisions.Mont. Pub. Interest Group v. Johnson, 361 F.Supp.2d 1222, 1230 (D. Mont. 2005).

Commentary

What is an “appropriation?"

The Montana Supreme Court has established a fairly narrow definition of “appropriation” in the context of the Montana Constitution. Curiously, the issue has never been decided on Art. III, Sec. 4(1) but the definition can be applied from decisions on other areas of the Montana Constitution. Case precedent on the subject reaches back to 1925, before the current constitution was ratified by the Montanan people. Recent court decisions adhere to this established precedence. The Montana Supreme Court draws a distinction between allocation and appropriation created by initiative. The Court has, on many occasions, highlighted the importance of the power of the people as the reason for such a narrow definition of appropriation. Some states with comparative Constitutions have adapted similar definitions of appropriation by initiative, while others have crafted rules that contrast with Montana.

The definition of appropriation was provided in 1921 in State ex rel. Bonner v. Dixon. 59 Mont. 58, 195 P. 841 (1921). At that time, the prohibition on appropriation by initiative was contained in Art. V, §1, but the language was essentially the same. The issue in Dixon was raised when an initiative was passed that created an allocation of bond revenue to certain buildings at educational institutions. The Court held that since the money derived from the bonds was to be placed in a designated fund, and no specific appropriation of that fund existed in the initiative, it did not infringe on the Constitution. The Court held that the use of “appropriation” in the Constitution “was evidently intended to be used in its strict sense of setting aside certain funds in the state treasury for a definite purpose.” Id., 59 Mont. at 70, 195 P. at 842 (1921).

A more recent case involving the definition of “appropriation” in the Montana Constitution involved, not initiative, but a referendum on a legislative act which revised state income and corporate tax laws. Nicholson v. Cooney, 265 Mont. 406, 877 P.2d 486 (1994). In holding the measure constitutional, the Court summarized the Montana definition: “’Appropriation’ means an authority from the law-making body in legal form to apply sums of money out of that which may be in the treasury in a given year, to specified objects or demands against the state.” Id., 265 Mont. at 415, 877 P.2d at 491. The Court again drew distinction between allocations to certain funds (constitutionally permitted) and appropriations to specific objects (unconstitutional).

The most recent Montana case that challenged the Constitutionality of a ballot issue on the grounds of impermissible appropriations came in 2001 in the Lewis & Clark County Court. In Lee v. State, the Attorney General rejected a referendum petition on the ground that the referendum sought an appropriation of money. 2001 Mont. Dist. LEXIS 1854, 4. In holding the referendum as constitutional, the district court highlighted Supreme Court rulings that differentiated between allocations and appropriations. Id. at 16. The court summarized the definition of appropriation as “an authority of the legislature in legal form to apply sums of money from the State's public operating funds to a specified public object or demand against the state.” Id. at 15.

The Montana Supreme Court noted the difference between an allocation and an appropriation in State ex rel. Haynes, 106 Mont. 470, 480, 78 P.2d 937, 943 (1938). The difference is that an allocation cannot be disbursed without further legislation. Id. 106 Mont. at 480, 78 P.2d at 943. In Haynes, the money allocated to the state public school system could only be distributed by additional independent legislative direction. The Court here appears to have drawn the line on appropriation by initiative when the initiative commands the legislature to disburse the allocated funds. The theory is that appropriation would take the distinct appropriations power from the legislature, while allocations allow for final decisions by the legislature and the power remains.

The Montana Supreme Court often draws on other state interpretations of similar constitutional provisions. For example, in Haynes, the Court draws on Arizona’s interpretation of a similar constitutional bar to appropriation by initiative. Haynes, 106 Mont. at 480, 78 P.2d at 943. Arizona has since broadened their definition of an appropriation to prohibit the creation of several special funds. Rios v. Symington, 172 Ariz. 3,8, 833 P.2d 20, 25 (Ariz. 1992).

The Alaska Supreme Court laid out their analysis of an appropriation in 1991: “we must ask whether the initiative would set aside a certain specified amount of money or property for a specific purpose or object in such a manner that is executable, mandatory, and reasonably definite with no further legislative action.” Fairbanks v. Fairbanks Convention & Visitors Bureau, 818 P.2d 1153, 1157 (Alaska 1991). The Alaska Court seems to draw a more narrow definition than Montana, limiting allocations that become appropriations in such a limiting fashion that the legislature loses their power to appropriate.

The District of Columbia takes an even broader approach to defining appropriations. In D.C. Bd. of Elections v. District of Columbia, the DC Court of Appeals struck down an initiative measure because the measure intruded on the discretion of elected officials. The DC court held that a measure to refer drug offenders to treatment "would intrude upon the discretion of the Council to allocate District government revenues in the budget process.” D.C. Bd. of Elections v. District of Columbia, 866 A.2d 788, 794 (D.C. 2005). The DC court reasoned further that the appropriation “is not a proper subject for initiative. . . whether or not the initiative would raise new revenues." Id.

A recent filing in the Lewis and Clark district court challenges the constitutionality of I-190, a people’s initiative, on the legality of Marijuana. I-190 institutes a 20% tax on all marijuana sales and directs “10.5% of the tax revenue going to the state general fund, with the remainder dedicated to accounts for conservation programs, substance abuse treatment, veterans’ services, healthcare costs, and localities where marijuana is sold.” Montana Ballot Initiative No. 190 (2020). Opponents of the initiative have claimed that the allocation of tax revenue is an impermissible appropriation, while the state maintains that the legislature retains the ultimate appropriations power to spend the additional money. A decision in accordance with Montana precedent would hold true to the broad definition of appropriations, that the allocations of revenue do not represent a denial of power from the legislature and are within the rights of the people of Montana.

The Court has not signaled a departure from precedence in recent decisions, but, if the argument is strong enough, could employ an interpretation from another state and rule in favor of the opponents of the initiative. Under Arizona, Alaska, and the District of Columbia’s definition of appropriation, I-190 would represent an impermissible attempt to intrude on the discretion of the government when it directed money to several specific funds, resulting in an allocation that is reasonably definite without further legislative action.

While other states may use a broader definition of appropriation, Montana justifies their narrow definition as a conveyance of more power to the people. The Supreme Court values the power of the people, citing provisions in the Constitution as well as past decisions that recognize the reason for initiative. See Nicholson v. Cooney, 265 Mont. 406, 877 P.2d 486 (1994). The Court has crafted such a narrow definition of appropriation because "initiative and referendum provisions of the Constitution should be broadly construed to maintain the maximum power in the people." Id. 265 Mont. at 411, 877 P.2d at 488 (1994). If the Court was to define the limit on initiative and referendum more broadly, it would be infringing on the power of the people guaranteed in Art. II, Sections 1 and 2.

The definition of appropriation used by the Montana courts is rooted in a long line of precedent and as currently established, provides a broad power to the people’s initiative.